Back in 2010, when I first started this column dedicated to the individual films offered in Criterion’s Eclipse Series, I had the full range of possibilities before me as to thematic reasons that I would choose a particular title to review that week. National holidays, current events, new movie releases and Hollywood rumors, chronological or directorial linkage to other films I was reviewing in my Criterion Reflections blog, all these rationale and more gave me a sense of direction and purpose in making my weekly selections. Now, as I’m not too far from the completion of my third year at it, the column is no longer quite weekly (more like intermittent, as I squeeze it in between other reviews and life demands.) There are fewer unreviewed Eclipse DVDs to choose from and the threads that connect my reviews and make them something other than just random pluckings from my shelf grow ever thinner. This week’s choice illustrates just how desperate I’ve become. I chose Pleasures of the Flesh, from Eclipse Series 21: Oshima’s Outlaw Sixties, simply because its title fit with the “something of the something” synchronicity I noticed in my most recent (Youth of the Beast) and upcoming (Lord of the Flies) reviews over at Criterion Reflections. But as it turned out, there’s a wonderfully cynical synergy that links these three films together much more effectively than their corny titular similarities could ever have suggested.

And it’s a good thing that this flimsy pretext nudged me to return to this fascinating but somewhat impenetrable box (in comparison to other Eclipse offerings that I think are much easier to approach and enjoy.) My first encounter with Oshima came back in August of 2010 when I reviewed Japanese Summer: Double Suicide, one of the later films in this Eclipse set. Even though my review was positive and I found it all quite interesting, my memory of watching it is of feeling more befuddled than usual – I knew there was something unique and intelligent going on, but I’d hardly consider it the ideal first impression of Oshima’s work. By that point in his career, his iconoclasm and abstraction were in full bloom, to be best appreciated by those who’d followed his progression through films closer to conventional narratives but still focused on Oshima’s characteristic themes of erotic obsession, self-loathing, relational aggression and humiliation and a calloused indifference to commonly observed social norms. The appeal of these motifs certainly varies from person to person, but even those who may not find themselves so easily relating to Oshima’s twisted regard for humanity can find impressive visual splendor and lyric beauty in his compositions and more experimental flourishes.

Pleasures of the Flesh, with its lurid but potentially and maybe deliberately misleading title (it’s based on the novel Pleasures in the Coffin), is the earliest of the five films in Oshima’s Outlaw Sixties. The set notably jumps past Oshima’s powerful trio of early films (The Sun’s Burial, Cruel Story of Youth, Night and Fog in Japan), all of which are available on Hulu Plus. Watching them back at the end of 2011, I was quite impressed and wondered why they weren’t part of an Eclipse set (or regular Criterion releases) of their own. While I still hold out hope that we’ll get those films in durable media someday, I have a better sense of what led Criterion to initially issue these selections from a bit later in his career. By 1965, just a few years into being a director for hire under contract to Shochiku Ltd., Oshima had already had his fill of the compromises and interference forced upon him by the studio bosses, so he formed his own independent production company, a gutsy move for an auteur still in his early 30s with a decidedly indifferent attitude to making mainstream commercial entertainment, even if his early efforts had generated considerable interest and a degree of box office success. Oshima clearly wasn’t in it for the money.

What Oshima was in it for, apparently, was to illustrate the unraveling of Atsushi, a particularly sad and purposeless young man, driven to despair and bottomless apathy by his unrequited love for a beautiful woman, Shoko, whom he met after being hired as her tutor, when she was a mere high school student. Learning of horrific abuse she’d suffered as child, Atsushi took it upon himself to exact vengeance upon the man who raped her after the pedophile suddenly re-entered the scene, intent on extorting Shoko’s family. But after his violent retribution was spotted by Hayami, a scheming embezzler, Atshushi finds himself wrapped up in a bizarre predicament: his assignment, in order to avoid the heavy jail time awaiting him if his crime is discovered, is to stand guard over a suitcase filled with 30 million yen, living out of contact with his fellow humans and never once touching the cash, while the man who stole it serves a modest prison sentence for his white-collar crime. Hayami’s plan is to reclaim the money after he’s released, secure in the knowledge that Atshushi won’t squeal because he’s guilty of a much greater crime, at least in the eyes of Japanese law.

Along the way, Shoko gets engaged and married to another man, seemingly oblivious to the ardent desire her lovestruck teacher can barely contain – or perhaps she sees it perfectly well, but enjoys the opportunities for cruel flirtatious sadism that his devotion creates. Her indifference to Atsushi and his pent-up frustration, unable to find a satisfying release as he broods over the futility and injustice of his situation, begins to mess with his mind, and before too long, the boundaries between imagination and reality begin to blur. The set-up is admittedly flimsy and preposterous – it’s easy to propose any number of alternative courses of action that Atsushi might have taken for the sake of his safety and mental health, instead of the choice he did make, to violate his agreement with the crook.

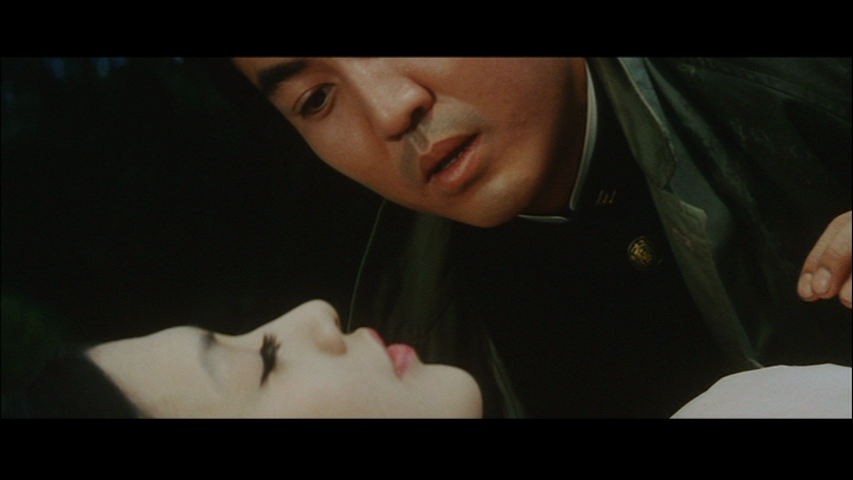

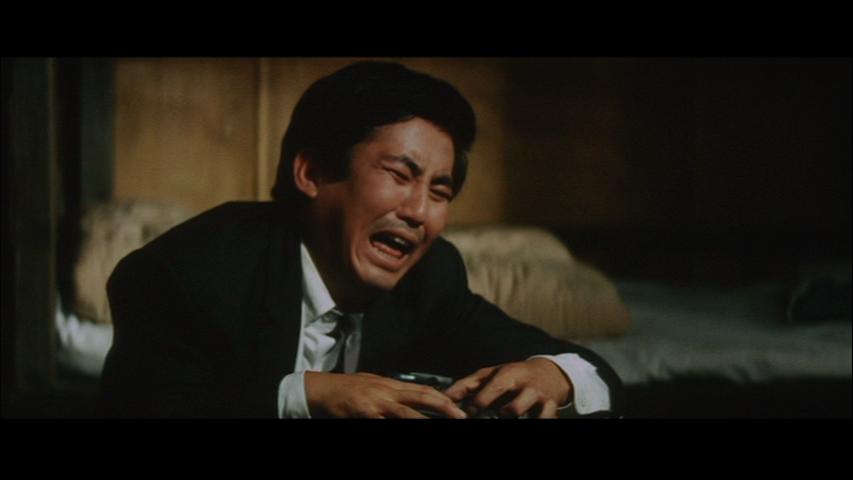

Atsushi’s will power breaks down after succumbing to the allure of hallucinatory madness as he begins to see Shoko appear in the flesh, though only as a phantom of his imagination. The necessity or likelihood of a young man getting so entrenched in his obsession that he’d forsake all other outlets may seem a bit implausible once we stop to consider it, but such nit-picking serves no useful purpose. The central dilemma is more existentially poignant than any practical advice we could come up for someone facing Atsushi’s dilemma. Oshima’s purpose is to confront the viewer with a scenario in which a man has no relational roots to hold him back from acting out his self-indulgent, nihilistic death wish, and all the freedom to do so, once he decides to just go ahead and spend all that money over the course of a year that he intends to finish up with a final act of suicide.

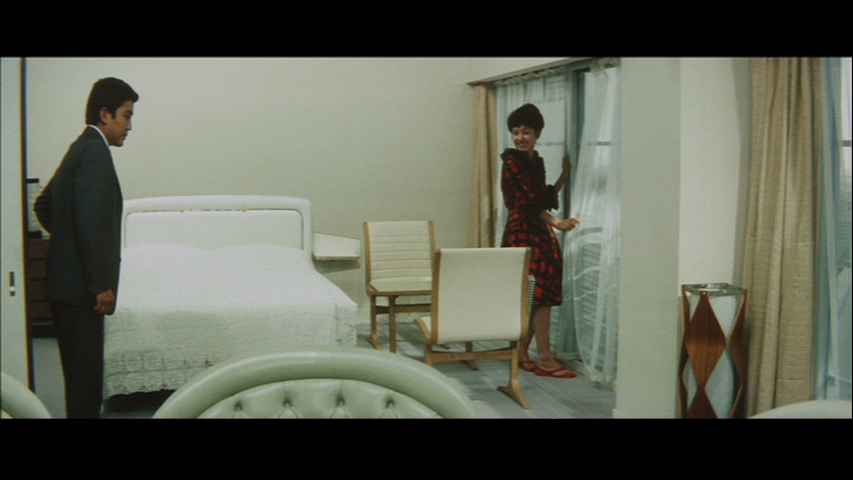

Atsushi, now freed from the hideous burden of responsibility that his fear of incarceration and the sense of duty inculcated within him by his conventional moral upbringing, promptly sets out on an ever-widening prowl for attractive women willing to allow him to lavish his money on them. The four objects of his lust fall into a descending trajectory, each one an apparent step down from the spoiled rich girl Shoko in the social hierarchy. His first conquest is an aspiring model and actress whom he picks up in a bar after he accosts her in the restroom with an incredulous request to move in with her in exchange for generous monthly payments. She takes him up on his offer, once he produces an impressive fistful of cash.

The passionate, spontaneous desperation, moral bankruptcy and even the bright whiteness of the early hotel room scenes triggered an unmistakeable Pierrot le fou vibe, not all that surprising from a director often referred to as “the Japanese Godard.” What did surprise me was the discovery that Pleasures of the Flesh was released in Japan on the very same day that Pierrot le fou debuted at the Venice Film Festival, according to IMDb. I checked, because I wanted to see which film might have exercised an influence on the other. But it turns out that both Godard and Oshima were grabbing the same vapors from the zeitgeist back in 1965.

This Japanese trailer, though lacking English subtitles, offers a tantalizing example of how Pleasures of the Flesh was marketed upon its original release. It probably has the effect of making the film seem a lot more sexy and action packed than it really is, though the music is appropriately creepy and unsettling. Look for a cool “making of” shot toward the end of the clip featuring Oshima riding the dolly right next to his camera!

As Atshushi blasts his way through other “types” of women likely to be seized upon by Japanese pick-up artists of that era (the melancholy housewife married to an indifferent loser, a medical student living on her own and vulnerable to smooth talkers, finally a hapless prostitute willing to give herself over to just about anyone who would have her), Oshima’s scenarios become more impressionistic and convoluted. Gangsters, husbands, lovers and even the ghosts of Atshushi’s memories intrude on his efforts to escape his depressing death-spiral through immersion in sensual pleasures.

Each encounter begins with an illusory sense of satisfied conquest, as Atsushi’s money, good looks and reckless determination swiftly break down the resistance that each woman initially puts up in response to his odd come-on. But just as quickly, disillusionment sets in as the baggage he brings into the new relationship proves toxic when intermingled with each woman’s hang-ups and complications. Even with enough money at his disposal to at least temporarily cast aside any material concerns, Atsushi finds himself growing quickly bored and emotionally numb to his lovers’ needs. He’s not presented as an especially harsh or unlikable protagonist – just supremely jaded and beyond the point where he can be convinced that any of these women, or any other he might chance upon, can offer a good reason to dissuade him from his ruinous plans.

Responsibility for Atshushi’s cynicism is not found through any fault of the women themselves – they’re all flawed in their own way, of course, but he’s the one who’s fucked up in the head. Oshima makes that abundantly clear as we see Shoko’s apparitions become more frequent, and increasingly morbid in their erotic sensibility. Having had his fill of sex over the preceding year (though never graphically portrayed, in accordance with the censorship restrictions of that time), Atsushi can only resort to violence (and maybe drugs?) to get his kicks, and when those cheap thrills run their course, all he can do is move on to the annihilation that he knows he abundantly deserves.

Fortunately for us, Oshima himself was not so burned out and bored with the futilities of existence that he didn’t bother to create a film worth admiring for its aesthetic pleasures, regardless of the bleakness of its overall message. In this bold return to film after a few years in limbo as he battled it out with the studios, he concocted several sequences of disorienting, dreamy surrealism that are simply wonderful and worth repeating just for the sensual moods they evoke, small oases of enchantment and escape amid the barren desolation of a cold, consuming universe. Just as the film that bears its title illustrates, Pleasures of the Flesh, gratifying as they can be in the moment, can only last so long, and can only offer so much, before a craving for something else begins to be felt, eroding whatever satisfactions at least temporarily blotted out the recognition of that void.