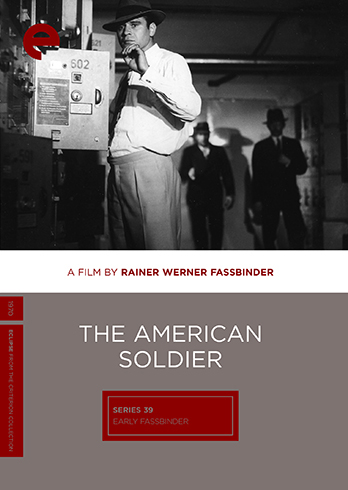

Given all the geopolitical turbulence, controversy and justifiable outrage filling the news headlines this week regarding an anticipated US military attack on Syria, one might draw the conclusion that I chose to review The American Soldier simply on the basis of its subject’s relevance to current events. Especially as the title relates to our nation’s self-appointed role as the ultimate global “peace-keeper” when strategically important societies begin to spiral out of control. But that’s not the case here, though I won’t apologize for the unintended synchronicity. Actually, this next run of installments in my Journey Through the Eclipse Series (which admittedly has slowed to a trickle, roughly equivalent with the diminishing flow of new Eclipse films in 2013) is going to be linked to movies that I’m reviewing on my Criterion Reflections blog. Basically, I’m looking for thematic parallels. Since I just reviewed Don Siegel’s The Killers, about a pair of cold-blooded hit men, I’m going to start my coverage of the new Eclipse Series 39: Early Fassbinder set by plunging right into the middle of it, with the third film released (chronologically) of the five included in that box. Like The Killers, The American Soldier chronicles the sociopathic adventures of a murderous enigma hired to shoot his gun at designated targets… no questions asked.

At some point, probably toward the end of my coverage of this box over the next month or so, I’ll offer more of a cumulative verdict on this set. But here’s a hint: Early Fassbinder is not for everyone. It took a bit of adjustment on my part to get into these films, but I was coming off a stretch of watching rather warm and emotionally affecting films from Kenji Mizoguchi and Satyajit Ray. Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s approach connects with a different part of my brain, and if forced to choose, I’d still have to side with the compassionate humanists like Ray and Mizoguchi over the decadent nihilistic burnouts like Fassbinder every time. But that doesn’t mean there’s not plenty to admire and simply enjoy in Fassbinder’s cinematic art. It’s just a matter of approaching it in the right mood and mindset. With the end of summer, the earlier darkening of the evening skies, and an imminent plunge of our country into a new round of war-making, I’m confident that Fassbinder’s jaundiced cynicism will yield further dividends with each repeated visit.

The American Soldier begins with a slow and seemingly tedious prologue, involving a trio of men playing a game of high-stakes poker with pornographic playing cards while the girlfriend of one of them idly paints her toenails in the corner of the room. Another idle, wasted night in late 60s Munich. The ticking of the clock fills the void between mumbled inquiries as to whether or not bets will be seen or if folding will occur. Fortunes tip in favor of the apparent leader of the group, leading his two flunkies to find some other source of consolation, even something as feeble as a momentary fantasy involving the shameless sluts pictured on the 3 of Spades. Another wager is ventured, but before any bluffs are called, finally… finally the phone rings. The American Soldier has arrived, armed with a pistol and a theme song: “So Much Tenderness” with English-language lyrics penned by Fassbinder and his colleague Peer Raben, sung in tones reminiscent of Jim Morrison by Fassbinder’s man-crush obsession at the time, Gunther Kaufmann.)

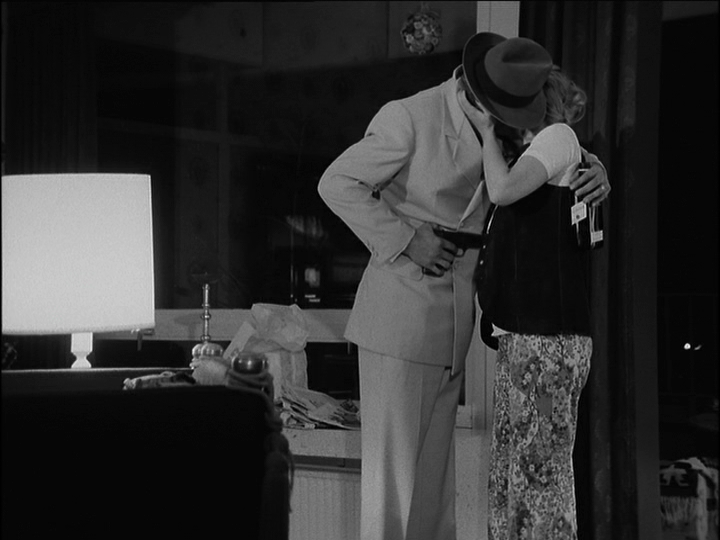

And of course, that soldier turns out to be a cold-hearted, hard-drinking, utterly calloused bastard. What else would we expect? Upon landing from his foreign point of departure, it doesn’t take too long for the warrior to pick up a prostitute who’s in the mood for some legendary Americanized “fantastic sex”, but she talks too much, basically evaporating any interest he might have in furthering his acquaintance. He pulls over into an empty late-night parking lot, flings her out onto the pavement, fires a few shots at her, drives away chuckling. Arrogant, cocky son of a bitch. Next thing you know, he checks into some low-rent hotel, orders a fifth of scotch from room service and treats himself to a voluptuous smooch from the hot-to-trot barmaid who delivers it before unceremoniously dismissing her for the night.

We learn that The American Soldier, who’s named Ricky, is actually the son of an American dad and a German mother, a veteran of the war in Vietnam, just returned to his native land in order to accept a contract for murder from that trio of gamblers we met in the opening scene. They turn out to be corrupt police officers who need to rely on extra-legal means to clean up some of their unfinished business. Up against a hard-to-crack case and under heavy pressure from their chief to get the suspects talking, the cops figure it would make their lives easier if they could just hire someone to take out the criminals entirely, without the awkward necessity of leaving any of their fingerprints on the hit. Ricky has sufficient local connections and credibility to infiltrated the Munich underworld, but can also just as easily disappear when the dirty work is done. Upon his arrival, he’s immediately drawn to reconnect with his childhood friend Franz, played by Fassbinder, who fancies himself some kind of henchman to the charismatic assassin at the heart of this lurid tale.

The execution of his assignment compels Ricky to ingratiate himself with a few of the corrupted types who populate this sleazy milieu. Cabaret singers, floozy barmaids, gay gypsy hustlers all get their chance to flaunt their charisma in Ricky’s implacable face. He remains steadfastly unimpressed. He’s been in the war, he’s seen it all. He only has one purpose – to kill. Getting a little booze in his gut and copping a feel here and there only serves to steady the nerves.

But don’t let this plot recap give you any false impressions. The American Soldier isn’t so much about story-telling or conveying any kind of poignant message or socio-political commentary. Fassbinder’s film, like most of these in this set, is about impression and attitude, provoking our emotions through alarming images of casual sex and brutality (often in close juxtaposition) in scenes that draw upon the iconography and well-established tropes of classic film noir – just taking some of those scenes further in explicit depiction of what was implied than earlier standards of censorship and decorum had allowed. Occasionally, these digressions venture into deeply absurd territory, such as when a chambermaid (played by future director Margarethe von Trotta) prattles on with an incongruous, seemingly pointless anecdote while a naked couple cavorts in bed behind her.

Still, Fassbinder isn’t completely uninterested in telling a story, so we do get some further narrative development as we meet Ricky’s mother and younger brother in a brief reunion scene as he visits their home after doing the deeds that he was hired to perform. The mother seems a bit too cold and distant, while the brother appears to have some seriously unresolved attachment issues that burden him with an excessively sensitive temperament – bearing the full load of emotional sensitivity that his brother Ricky lost somewhere along the way. The familial enmeshment takes on proportions both pathetic and pathological, resulting in a fatal distraction at a crucial moment and a marvelously ludicrous slo-mo death scene to close things out. “So much tenderness.”