After wrapping up last week’s omnibus review of the new Eclipse set from Jean-Pierre Gorin with a look at violent urban gangs, my film-watching focus over the past several days shifted slightly to zoom in on the hired killers who specialize in doing much of their dirtiest work. On my Criterion Reflections blog, I reviewed Alan Baron’s proto-indie New York hit-man B-movie Blast of Silence, so for this week’s leg of my Journey Through the Eclipse Series, I’ve chosen what amounts to a Japanese companion piece, filmed six years later and with the benefit of major studio backing, a budding star on the rise and a more conventional narrative approach. But the thematic similarities between Blast of Silence and A Colt Is My Passport, from Eclipse Series 17: Nikkatsu Noir, link the two films together in spirit much more than their differences drive them apart.

Beyond several amusing surface similarities (emerging through tunnels, urban freeway location shots, testy remote conversations between hitman and headquarters, among others,) Colt and Blast both maintain a long steady gaze on the mechanics and logistics of pulling off a clean, efficient assassination, often putting the viewer directly into a first-person perspective as the executioner goes through his routines, trailing his target, casing the environment where the hit will take place, preparing his weapons and always taking care to avoid leaving a trail of evidence that points in his direction. Each of the protagonists function effectively as anti-heroes, as they persuade us to root for their successful escape from the dangers their chosen profession inevitably places them in, despite the murderous criminality of the whole enterprise. Frankie Bono, the front man in Blast of Silence, and Kamimura, who carries a Colt as his passport (in addition to a regular old paper passport, just to expedite his trips to the airport, we learn early on) are hard-bitten loners, though of the two, Bono is by far the more cynical and unremittingly sociopathic. Kamimura’s back story remains much more elusive to us than Frankie’s; we learn practically nothing about what pushed him into this line of work, but no doubt remains in our minds about how good Kamimura is at it. Unlike the American film, where the hit takes place toward the end of the movie, after a few delays and fumbles on Frankie’s part, A Colt Is My Passport moves swiftly from Kamimura taking the contract straight to its ruthless fulfillment – a job carried out just a bit too efficiently to suit his gang boss, as it turns out. Not to mention the hurt feelings of the rival gang whose leader just got snuffed.

But before I get further into the film itself, a few words about director Takashi Nomura – and a very few words they will be, indeed, since I really can’t find much information about him! From what I can gather at IMDb, he worked primarily in the Japanese TV industry after failing to make much of an impact as a feature film director (as was also the case with Blast of Silence director Alan Baron, who spent most of his career directing episodes of American TV shows like The Love Boat and Charlie’s Angels in the 1970s and 80s.) Nomura’s anonymity kind of fits with A Colt Is My Passport‘s lack of a compelling visual signature – even though it’s a fine example of its genre, competently assembled and quite entertaining on its own terms, there’s nothing nearly as auteuristic going on here, no crazy camera perspectives or transgressive boundary pushing, as one finds in Suzuki’s Take Aim at the Police Van, Kurahara’s I Am Waiting or Masuda’s Rusty Knife. With A Colt Is My Passport being the latest entry in the Nikkatsu Noir box, its plot and presentation have a bit more of a formulaic, by-the-numbers feel to it. But it’s a formula that’s reached a point of perfection, making this offering a nicely balanced, mature example of the genre, a good one to share with friends who might be relatively new to yakuza flicks, of the vintage variety anyway…

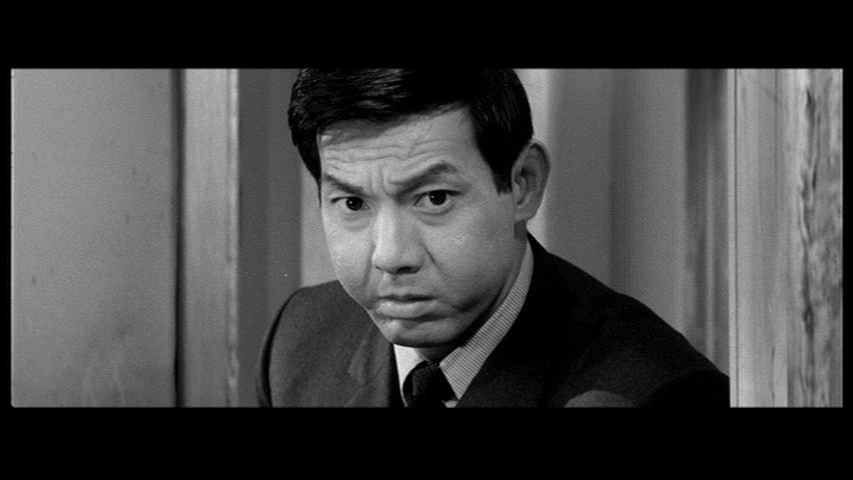

The compelling presence throughout the proceedings is, of course, Joe Shishido, a face and persona instantly familiar to just about anyone who’s been exposed to Japanese action films of this era. It’s practically impossible to refer to him in a review without making mention of his surgically-enhanced cheeks, so now that I got that out of the way, let me just say that he deserves more credit for his ability to project stoic determination and calm, unblinking fierceness in the face of life-threatening adversity. If you want tagline spewing wisecrackers or muscle-flexing pretty boys in your shoot-em-ups, Shishido is not the guy for the job. But I’ll take his calculating steely intensity over that nonsense any day. As the trailer below puts it, he’s “as hard-boiled as they come.”

I’m not sure if A Colt Is My Passport ever received general distribution in the West prior to just a few years ago, when it briefly hit the festival circuit prior to its 2009 release on DVD. But if American distributors would have preferred a less cumbersome title, they could have just called it “Assassination Clinic,” because that’s pretty much what we get in the first half-hour or so of the film.

It’s not just Kamimura’s methodical efficiency in taking down his target, but also how he goes about maneuvering his way through the complications that ensue. To better highlight how far Kamimura has progressed in the discipline’s associated with being a hired gun, he’s paired up with Shun Shiozaki, his driver and young apprentice, so to speak, played another Japanese actor with a westernized name and appearance, Jerry Fujio. His sidekick role presents the opportunity for the elder assassin to offer clipped pearls of wisdom. When asked how the target died, Kamimura coldly replies, “No different, same as they always do.” And after casually tossing the murder weapon, a valuable, highly calibrated rifle, complete with scope and silencer, into a car about to be incinerated and crushed at the local scrapyard, Kamimura reprimands his protege who’s appalled at the waste, “If you want to stay alive, don’t get too attached to your guns.”

That same dispassionate detachment pervades nearly all of Kamimura’s actions throughout A Colt Is My Passport, as he understands at a deep level the cruel transiency of his role in the gang. Just as he lacks sentimental attachment to his tools, even disposing of a car that he had customized especially for the job when that became necessary. Beyond the voyeuristic thrills and suspense that a film like this delivers, a deeper subtext for its appeal may be seen in how Kamimura’s attitude toward the objects he uses in his jobs mirrors the disposability with which he is regarded by his bosses, after he’s served his purpose in their schemes. Which in turn reflects the inherent fact that in an increasingly corporatized world, we’ve all become cheap, mass-produced commodities, at least in the eyes of our employers. Kamimura’s jaded recognition of the corrupted transaction that exists at the core of his relationship with the gang, his advance preparations to deal with that contingency when the gang no longer has a use for him, and the barely concealed chip of contempt on his shoulder for his bosses is key to understanding the appeal this cold-blooded grim reaper exerts over his mostly law-abiding audience.

To augment Shishido’s exemplary turn as a late 60s badass, we do see him demonstrate his own brand of honor among the thieves, as he helps young Shun escape from the pursuing thugs and befriends Mina, a young woman trying to scrape her way out of the lower depths, presently marooned at a cheap truck-stop motel that serves as Shun and Kamimura’s hideout. She dreams of a better life, wondering if these well-dressed strangers might be her ticket out, and puts herself at some risk to help the men when the bad guys come looking for them. It’s at this point that Kamimura and Frankie Bono part ways. Bono’s repressed rage made him a misanthropist through and through, unable to care about or relate with empathy to anyone around him. But Kamimura has a sense of himself as a protector to at least a few of the people in his life, despite his unwillingness to maintain any lasting relationship with them. So he manfully trades in his own security in order to give his friends a chance to experience a relief he’ll never know.

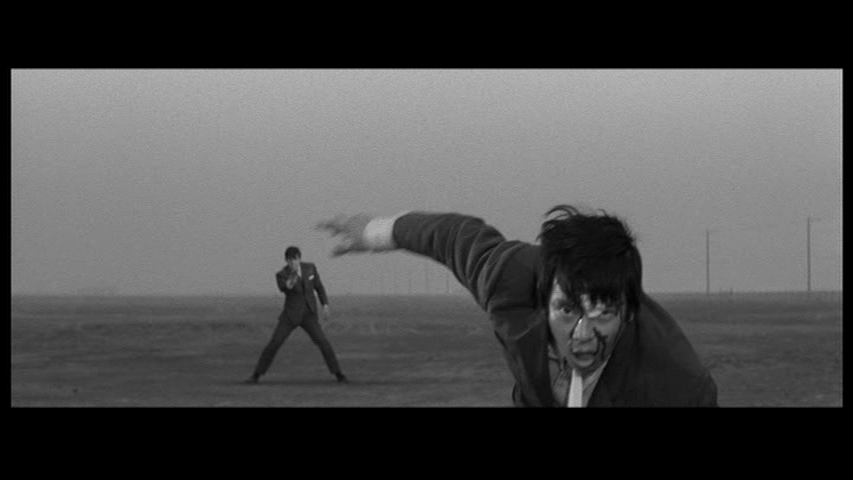

At a basic level, A Colt Is My Passport‘s main function as a story is to serve as set-up for the movie’s climactic finale, a big showdown between Kamimura and the vultures who’ve conspired to profit at his expense. With the assassination of the rival gang’s boss achieving the opposite outcome of what was seemingly expected, Kamimura finds himself in greater danger than ever as both gangs send out their most lethal enforcers to exact their revenge. The clip below shows the last and best of several setpiece gadget scenes in which Kamimura’s wily strategies work so perfectly to foil his adversaries that it pushes our credulity to the snapping point. Just a warning, the scene is a total spoiler, so don’t click on it if you haven’t seen the movie, unless you don’t mind seeing how it all ends.

So yeah, it’s all pretty unrealistic, and by today’s standards kind of crude in its composition and could have been choreographed with even more in-your-face kick-assedness. Modern action flicks easily surpass A Colt Is My Passport in that regard, I can’t help but agree. But that’s the legacy this movie and others like it created, that we enjoy so amply a generation or two later. Sometimes it’s good and necessary to strip away the CGI and set aside the high tech super-automatic weapons and acrobatic stunts in order to get back in touch with the dirt and sweat, the blood and brains, that inform the genre’s fascinating and fatalistic portrayal of modern masculinity.