After a few weeks of post-holiday dormancy, Criterion’s new release machine springs back to life this week, with some of the most hotly anticipated titles in recent memory starting things off on a winning note. Belle de Jour this week and Godzilla next Tuesday are the obvious and well-deserving headliners, but sneaking in from the margins of our overloaded attention spans is Eclipse Series 31: Three Popular Films by Jean-Pierre Gorin. In its own quiet way, this set of obscure documentaries, rarely viewed in recent years and never before available on DVD, has stirred up its own share of excitement, at least judging from a few comments I’ve seen in my Facebook and Twitter feeds.

I’m here today to confirm the anticipation and add to the mounting buzz: this is a fascinating collection that will reward multiple screenings and sustained engagement from viewers who appreciate cinema that takes them below the surface and deeper into the mysteries of how humans grow, develop and communicate within the peculiar environments we happen to be born into. My typical format for this column is to take a longer look at each individual film in the Eclipse Series, and I initially approached this box no differently. But after watching Poto and Cabengo, I was overwhelmed by curiosity about where Gorin would go next, so I had no choice but to watch the other titles in this set. I still intend to go back later and write separate posts dedicated to each film, but I figured readers here would appreciate an overview of the whole package, just to get the conversation rolling.

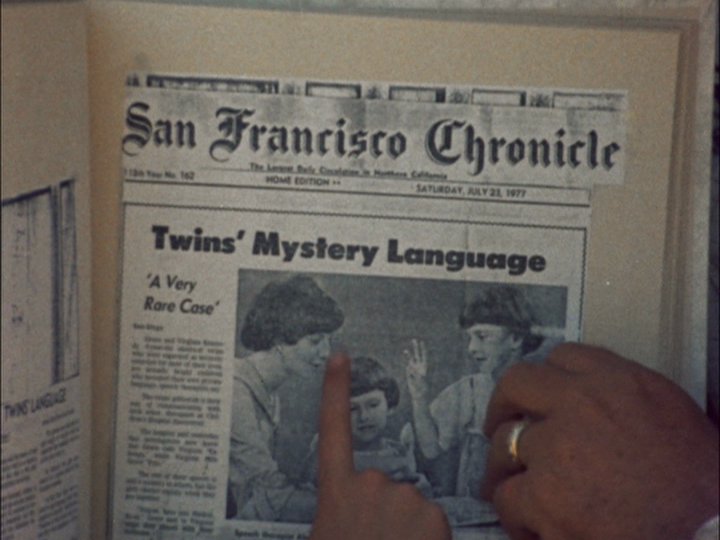

Poto and Cabengo introduces us to Virginia and Grace Kennedy, a pair of identical twins born in 1970 who became famous later that decade on account of an unusual private language developed between the two of them that initially baffled their parents, doctors and even professional linguists who were unable to extract any meaning out of the girls’ fluent verbal exchanges. As a father of twins myself, I have often joked with my sons about their “secret twin language,” playing off the idea that they shared some kind of enigmatic psychic bond unfathomable to us clueless singletons. So I was pretty eager to learn more about this strange phenomenon. I can only conclude now that some dim echo of the news coverage this story received in the late 1970s informed the running gag it became in our family over the years.

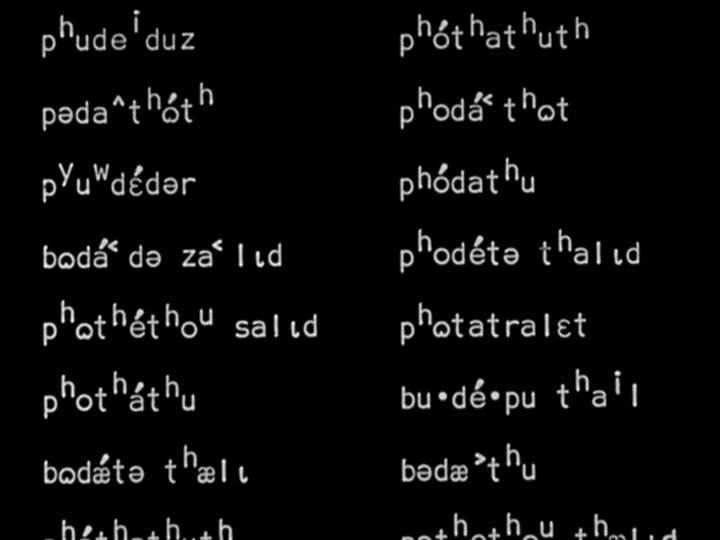

Jean-Pierre Gorin, who relocated from France to the balmy environment of Southern California in 1975 to take a faculty position at the University of California, San Diego, found himself an interesting subject for his first film after leaving the Dziga Vertov Group, a collaborative effort involving him and, most famously, Jean-Luc Godard. The clip above offers the first several minutes of Poto and Cabengo (the title is based on names the girls gave to each other). The graphic ? ? ? overlays grab our attention, urging us to open ourselves up to broader and more puzzling questions yet to come that go well beyond the simple “what are they saying?” that first scrolls across the screen. Though initial impressions might lead to speculation that the girls’ untranslatable syntax stems from some kind of spontaneous mutation or perhaps an innate ability that’s usually supressed by normal cultural conditioning, Gorin’s investigation leads to the sadder and more prosaic conclusion that the girls talk the way they do as a result of parental neglect and social isolation. But far from just addressing the “problem” and showing us the reparative conclusion achieved through therapeutic interventions, Poto and Cabengo teases out the tangled threads of language barriers, economic struggles and emotional frailties within their family that created such unusual symptoms within the girls. Pulling back from the micro-society that exists strictly between Virginia and Grace, Gorin reveals the pragmatically adjusted dysfunction of their parents’ failures and sense of dislocation in a social environment wholly apathetic in regard to their ability to thrive.

The film also documents the relentless appetite of the human imagination to take whatever bits and pieces present themselves to its manipulative powers and form them into something approaching coherence, even if only on the most subjective, individualistic terms. In a way, Gorin’s artistic methods, assembling seemingly random elements like old Katzenjammer Kids comics, higher-quality forms of “home movie” footage, wry self-deprecating voice-over commentary and deadpan displays of vintage all-American kitsch as only the mid-70s could produce, mimic what the girls were doing in their own childish, naive way, creating something new and uniquely individualistic, though more easily decipherable to those who share Gorin’s referential frame.

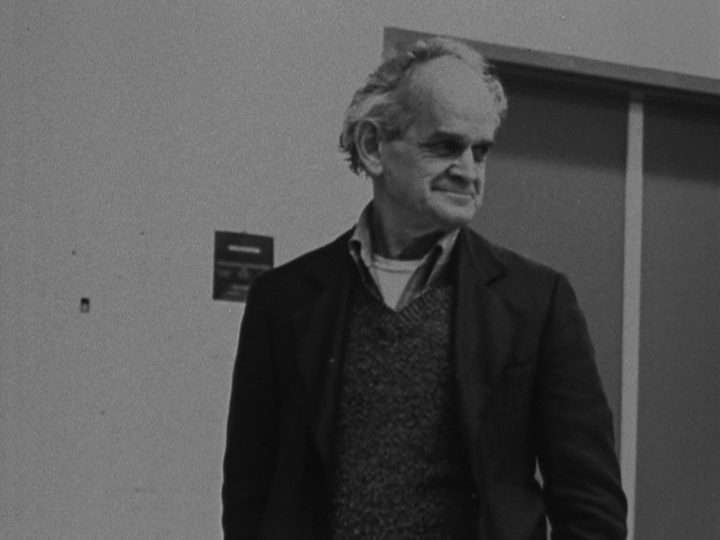

Parting ways with the by-products of poverty and cross-cultural alienation explored in Poto and Cabengo, Routine Pleasures, released six years later in 1986, reflects Gorin’s own assimilation process as he notes that filming began after his “fifth Fourth of July” in the USA, at which point he was “no longer French, but not quite American.” Following a wayward nostalgic impulse brought about by a touch of homesickness, he somehow crossed paths with the caretakers of the Pacific Beach & Western Railroad, a club of model train hobbyists who dedicated long hours and obsessive attention to detail in pursuing and perfecting their craft. Following that hankering for the past, Gorin got guarded permission from the club to document their activities, filming most of the early portions of Routine Pleasures in bluish-tinted black and white (switching to color at a strategic moment a little past the halfway mark.) As a simple portrayal of rather impressive work in recreating a world in 1/6th scale, Routine Pleasures would have easily lived up to its name if it did nothing more than celebrate the peculiar fascinations of these men, to be enjoyed by fellow train enthusiasts and others who geek out with similar zeal on their own respective pastimes. But of course, Gorin has higher aims than that, and after abruptly bringing the film’s opening to a halt, he introduces the second major subject of his discourse, the painting and life philosophy of his American mentor, Manny Farber.

Even though Farber refused to appear on camera, his presence comes through in Gorin’s paraphrases of his friend’s jaded ruminations and, more colorfully, through a pair of large scale paintings he was working on during the course of Gorin’s shooting. While Gorin takes a more gentle and accommodating approach in his interviews with members of the P.B & W., quietly indulging their eccentricity in order to draw them out more fully, the acerbic Farber pushes back hard against Gorin’s inquiries and musings, his blunt feedback provoking the filmmaker to continue digging deeper, questioning his own assumptions and to avoid the deadly trap of lapsing into overt seriousness in the development of his own art.

Routine Pleasures is an immensely likable film, with its charming close-ups of miniature railroad landscapes and street scenes (watch them carefully, they are loaded with visual jokes!), close examinations of Farber’s densely populated canvases and the irascible, socially awkward men who toss anecdotes back and forth in the later stages of their lives. The train men in particular reminded me of older relatives I’ve known over the years, men shaped by decades spent in manufacturing and military professions who wind up so programmed by their work environments that their idea of a fun time consists of reenacting tightly scheduled and precisely executed dispatching schemes for hours at a time.

It’s hard to think of a more jarring leap from the calm, folksy enclave of the Pacific Beach & Western Railroad to the violent street gangs of Long Beach, but the truth is, the worlds of Routine Pleasures and My Crasy Life weren’t too far apart from each other in either time or distance. Both of the environments are different kinds of boys clubs, I suppose we could say. Released in 1992, as the gangster rap fad was approaching its peak, My Crasy Life examines how a neighborhood populated by Samoan immigrants had adopted the hardcore look, language and criminal-minded attitude so prevalent in other impoverished communities of that time: LA Raiders and Kings hats, blue plaid flannels, gang-affiliated tattoos and a ruthless embrace of vicious revenge on anyone who harmed or even threatened their families or associates. In pop culture terms, this is probably the most entertaining and attention-grabbing film of the three, full of vintage rapping, free-flowing profanity and unhinged machismo as the Sons of Samoa fill us in on how they see the world and what keeps them strong in the face of so much adversity.

The clip above is the best I could find to offer a sample of My Crasy Life, but keep in mind that it’s recorded off of someone’s TV, so the quality is crap. It’s apparently made by a person who knew (or at least knew of) several individuals who appear in the segment. It starts on the island of American Samoa, where we’re quickly greeted and just as quickly dismissed, with the advice of taking the camera and crew back to the US mainland, specifically to 32nd Street in Long Beach, California, where we see rap group West Side Strong delivering their anthem with a few street life scenes spliced in to round out the picture.

But while there’s no shortage of grim intrigue in Gorin’s study of the SoCal Samoan gang scene, he’s not content to just focus on the more sensational elements of the story as he traces back the family and cultural roots of these ill-destined young men, wondering how they got where they were and what was happening in Samoa at that same time. The juxtaposition of these two geographically distant but now intimately linked subcultures, along with the subordinate thread of a concerned local beat cop and his interrogative HAL 9000-like dashboard computer, sets us up for a poignant conclusion, not at all the expected landing place we figured we’d arrive at when we first encountered these brawny disciples of N.W.A. and Eazy-E.

So there it is. I’m not sure how he pulled it off, but Gorin’s inquisitive eye and perceptive insight took him in remarkably divergent directions, resulting in a trio of films with seemingly disconnected subject matters, filmed on low budgets, six years apart from each other that somehow meander toward an astonishing contemplative unity at the end of it all. We’re very fortunate to have these gems retrieved from the dustbin.