With its potent mix of manic mood swings, shamelessly uninhibited scenery-gnawing from the actors and the trademark swoops and swirls of Koreyoshi Kurahara’s dive-bombing camera work, it would be easy and convenient to peg 1964’s Black Sun as a thoroughly bonkers exercise in mayhem, one of those crazy, unhinged Japanese films that touch upon extreme emotional registers unfamiliar to many Western viewers. No doubt, there’s plenty of screwball zaniness to be found in this, my last Journey Through the Eclipse Series entry for the films of 1964 (unless Criterion eventually decides to issue Eclipse versions of a few other titles from that year, like Ingmar Bergman’s All These Women, Bryan Forbes’ Seance on a Wet Afternoon, Mikio Naruse’s Yearning or Masahiro Shinoda’s Assassination, each of which I would gladly welcome after watching them on Criterion’s Hulu Plus channel.) Any viewer who just wants to take this film entirely for laughs can probably do so without much difficulty, though much of the humor comes at the expense of excruciating suffering by one or more of its characters. But step back a bit from the overt weirdness and histrionic over-acting, focus on the characters and be prepared to discover a film that touches a deeper nerve than you might expect after the last echoes of loony cackling laughter and primal death-screams have faded into silence.

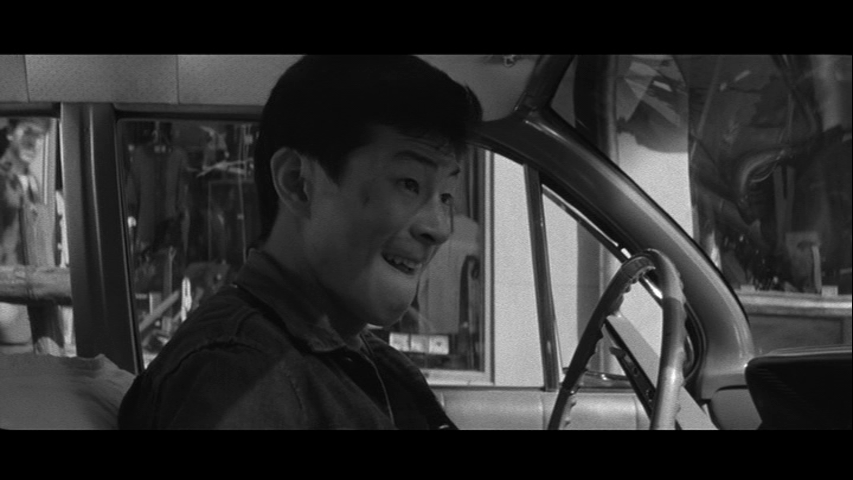

As mentioned in my review of Cruel Gun Story, the post accompanying this one as part of my year-ending Eclipse Series double-feature, Black Sun‘s bizarre character interactions take place within the context of the USA’s ongoing military presence in Japan some twenty years after Emperor Hirohito sent his emissaries to sign the documents of surrender that drew the Second World War to a close. The two men around whom this deranged plot pivots are Mei, a Japanese street scoundrel who makes his home up in the rafters of a bombed-out church, and Sgt. Gil Jackson, a black American soldier recently gone AWOL after shooting one of his fellow G.I.s to death in some kind of altercation, never clearly explained. Mei is the first character we meet, and the one whose perspective (with a few crucial exceptions) guides us through most of the narrative. We first see him engaging in a bit of thievery as he absconds with a few coils of copper wire that a group of men have been burning to strip away the rubber casing. He uses the money he gets from selling it to purchase an LP by the Max Roach Quartet from which the movie gets its name. Mei is a jazz nut, obsessively devoted to building his record collection despite the squalid poverty of his circumstances.

That tie-in yields great benefits for us viewers, as we’re treated to a vibrant, percussive soundtrack featuring a solid collection of jazz numbers by drummer Max Roach and his band. Especially memorable is the vocal performance of Abbey Lincoln. The clip embedded above features eight and a half minutes of the Quartet’s soundtrack music, with Lincoln’s rendition of “Six Bit Blues” kicking in right around the seven minute mark.

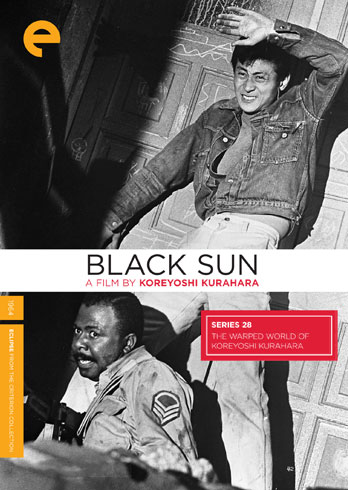

As for the director, Black Sun shows the man featured in Eclipse Series 28: The Warped World of Koreyoshi Kurahara scampering further along the wildly outstretched limb he’d been situated on since 1960’s The Warped Ones made him something of a sensation among the young filmmakers assigned to work on Sun Tribe pictures. After achieving mixed results (commercially, that is – I really enjoyed it myself) with Japanese megastar Yujiro Ishihara in I Hate But Love, Kurahara sought to recapture the old magic by recombining many of the elements that helped him stand out from the pack.

In fact, this film could be seen as a sequel of sorts to Kurahara’s breakthrough, in that it features the same lead actor (Tamio Kawaji, who also had a brief appearance in Cruel Gun Story), a jazz-infused soundtrack and a similarly hedonistic, “youth gone wild” theme at its core. A few of the scenes were even shot in the same bar showcased in The Warped Ones with its walls and ceiling plastered with images of iconic jazz musicians. These similarities lead Chuck Stephens, who wrote the DVD liner notes for this box, to assert that Kawaji plays the same character in both films, but that point remains debatable, in my opinion.

Chico Roland, the African-American actor who plays Gil here, also had a bit part in The Warped Ones. Kurahara must have liked what he saw there because he gives Roland what amounts to a second lead role in the film. Roland’s acting range is rather limited, from what I’ve seen of his work, and his rushed enunciation (almost always in strained, gasping English) is eccentric, to put it kindly. But he appears to have secured a successful niche for himself in the Japanese film industry at this time. He can also be seen in Suzuki’s Gate of Flesh, filmed in 1964 as well, and he returned to Japan a few years later to take on a role in Genocide, now found in the When Horror Came to Shochiku Eclipse set released in late 2012.

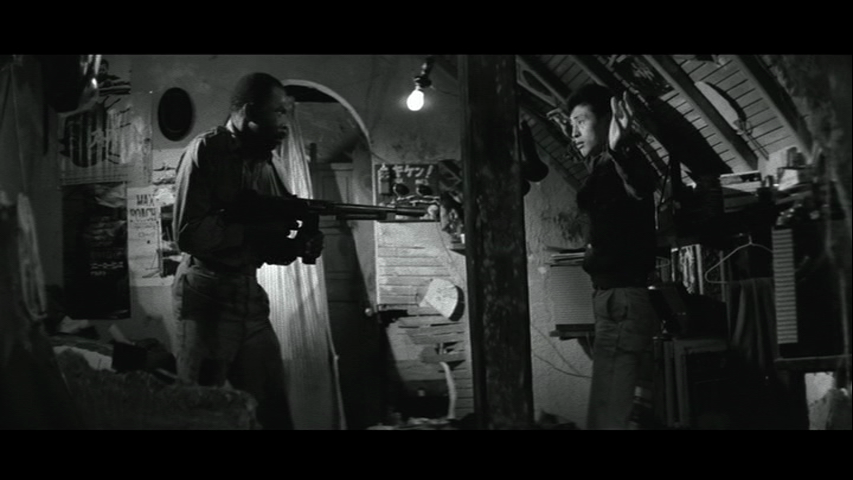

Much of Black Sun‘s intrigue grows out of the harsh and incongruous culture clash between the two miscreants as they forge an unlikely bond. Gil, badly wounded by a gunshot to his leg that has him perpetually trembling on the verge of delirium, veers between holding Mei as a hostage in case such a bargaining chip is needed when the MPs catch up and relying on him for basic first aid and transportation to facilitate his escape. For his part, Mei’s love of jazz has spawned a naive admiration for anyone with dark skin – who else would consider it his “lucky day” when he sees a crazed, bleeding, wild-eyed soldier break into his home pointing a monster-sized machine gun in his face? Despite the fact that Gil’s intrusion creates major problems for Mei, even to the point of killing his beloved dog named after Thelonius Monk, Mei can’t bring himself to betray Gil. Though he does indeed try to denounce his love of jazz and black people, the vibe runs much too deep for him to impulsively forsake. So for want of better judgment and any obvious motivation to take the safe and sensible course, given the shambles that his life is already in, Mei ends up taking enormous risks to help his new friend accomplish his dubious objectives.

Besides the swingin’ soundtrack and the bizarre fascination stirred up by Gil and Mei’s interactions, Kurahara’s unique eye for composition and his camera’s free-flying movements supply the other compelling reason to give Black Sun a spin. I’m assuming that the blasted husk of a church was a real location, not a fabricated set, but even if it wasn’t, Kurahara’s exploration of the building’s desecrated interior and rickety assembly of ladders and staircases is quite marvelous to behold. The angles are so acute and unusual that it often takes the eye a few moments to decipher what it’s looking at, lending the film some decent replay value.

And though the side story concerning Mei and his bar fly girlfriend Yuki is for the most part superfluous, she adds a touch of sexiness to the story when she and Mei let themselves go, shrieking and grappling each other furiously, accompanied by Roach’s spasmodic drumming with a blistering sax running wild over the top. The brief segment put me in touch with just how primal and passionate black American bebop must have sounded to young Japanese ears at the time.

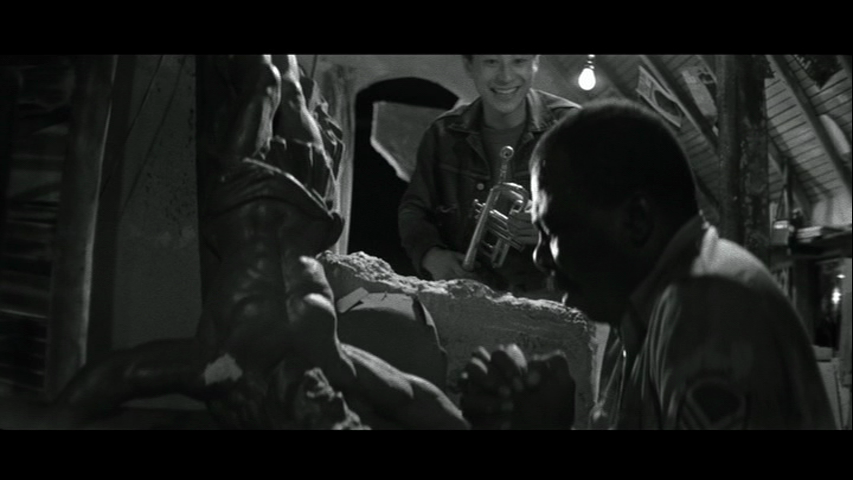

For all the energy and exuberance stirred up in the early portions of Black Sun, the film would turn out to be a fairly hollow exercise in style without something to hold the narrative together. We get that in the second half, after Mei and Gil have worked through their full push-pull cycle of repulsion, outrage and attraction. Once the alliance is forged, Mei recognizes that he needs to get Gil out of the neighborhood, but that’s a tall order given his lack of available funds and the fact that the district is crawling with MPs looking for a hard-t0-miss dark skinned fugitive. Almost instinctively, Mei stumbles upon an idea – swapping their skin color via readily available paint found in the church – that will buy them a little time and if it works out just right, might let Gil slip right through their dragnet. Part of Gil’s ruse depends on his ability to play the trumpet at least somewhat convincingly. Mei’s racially ignorant assumption, that all black people are naturally gifted musicians, gets exposed, along with a number of other ethnic stereotypes that, despite the crude delivery of the message, was probably quite illuminating to many in the film’s original audience.

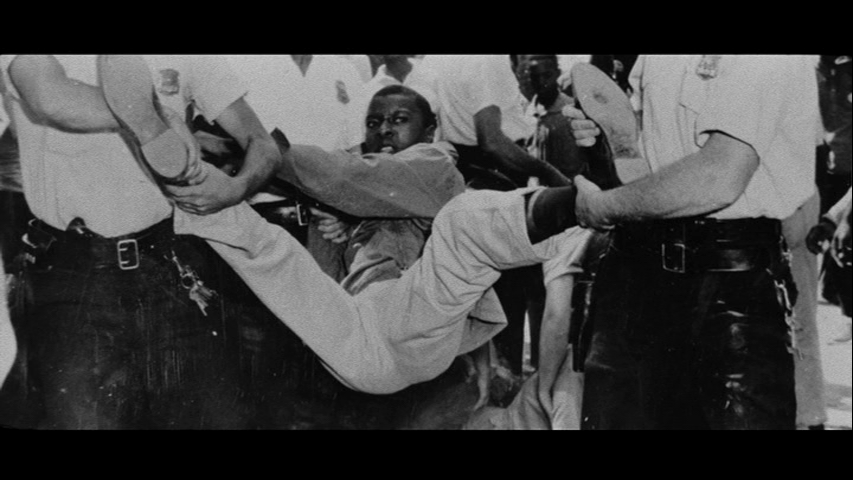

As Gil tries in vain to coax some kind of passable tune through his horn, he sees in the blank stares of the crowd surrounding him that he’s fooling nobody, and only risking his safety by giving up his anonymity. He begins an inexorable slide into mental breakdown, having flashbacks of his infantry training days, hallucinations of the sea and his mother, and most pointedly, scenes from the then-contemporary conflicts over civil rights that were raging in the USA. This short montage of beat-up documentary footage somehow obtained by Kurahara flies by pretty quickly, and the effect is not helped much by Chico Roland’s wheezing, over-cooked delivery – but once I deciphered what he was trying to communicate, I became a lot more empathetic to the struggle of each of these characters, and less of an amused/appalled gawker at the maudlin display of raw feelings so clumsily portrayed.

The spectacle, and Gil’s plight in particular, becomes ever more pathetic over Black Sun‘s final half-hour. The language barriers between Mei and his friend/kidnapper are never resolved, and the wounded soldier’s irrational insistence on going to the sea only compounds the problem, especially when Mei drops him off on the bank of a filthy reservoir clogged with industrial waste. Nearly insane from the pain, his energy dissipated by the loss of blood and lack of food and rest, Gil grows increasingly lethal and unstable – a truly dangerous “stray dog,” to borrow the familiar Japanese metaphor. But rather than portray him as a menace, or presenting Mei as a victim, Kurahara contradicts what many viewers then and now might have expected or desired. Gil, a personification of the “ugly American,” scary and disruptive as he may seem, is actually just as exploited, unwanted and out of place back in his home country as he is now, running and crawling for his life through the mud and rubble of a ruinous shipping yard.

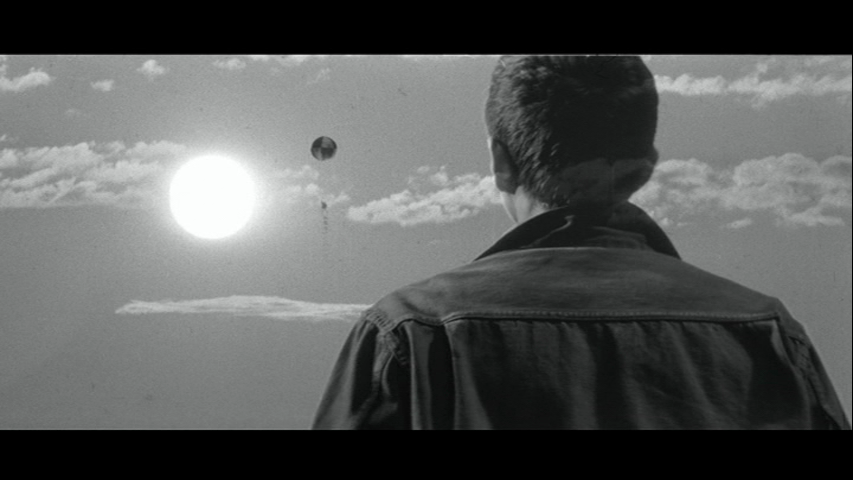

Though Gil gasps repeatedly that he doesn’t want to die, he feels its inevitable icy grip tightening upon him. Black Sun ends in a most memorable lunatic catharsis: a man without a country, homeless and exiled from every last nation on the earth, with his last and only friend firing the shot that sets him free, Gil has no other refuge to turn to than the haven provided by his infinite eternal mother – the sea, the sky and the sun.