Today is the day that a select group of Criterion loyalists have been anxiously awaiting for nearly a year now – or more precisely, since September 15, 2009. Those of you who recognize the 15th of each month primarily as “Criterion Upcoming Release Announcement Day” may remember last September’s Criterion news release a bit more clearly than some of the months before or since. It was the day that our favorite DVD publishers unveiled their plans to make the AK 100: 25 Films by Akira Kurosawa super-deluxe box set their one and only new product for the following December.

That set off a storm of protest from those who were expecting something more, or perhaps different, or at least more affordable than the nearly $400 SRP behemoth that housed 25 films by the venerable Akira Kurosawa in honor of the centenary of his birth, including twenty that had already been released as regular Criterion DVDs or as part of the Eclipse Postwar Kurosawa set. Among the complaints (which I personally considered embarrassing and small-minded on the part of my fellow Criterion fans) generated by this news was that five of the films contained in the sumptuous silk-lined box were not available for purchase other than as part of this package – and some folks were offended that Criterion was “forcing” them to buy an admittedly expensive commemorative edition if they wanted to have access to those rare Kurosawa works in convenient Region 1 DVD format.

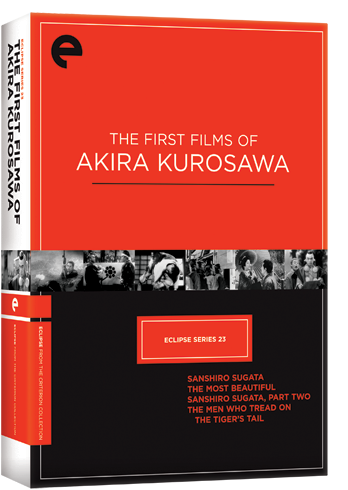

Those of us who knew better recognized that Criterion’s motives for releasing the AK 100 box were honorable above all else. Spare me the crass denunciations about cynical “double dipping” on their part. Kurosawa’s lifetime achievement and the unique occasion of the hundredth anniversary of his birth easily warranted a memento for the ages, and the AK 100 set serves that purpose exceedingly well. And we figured that it was just a matter of time before Criterion would find the right format for releasing those additional films. That time is now, with today’s release of Eclipse Series 23: The First Films of Akira Kurosawa. This newest addition to the Eclipse line subscribes to the truth in labeling laws – that’s exactly what you get: Kurosawa’s first four films, each produced in the fascinating and dire context of Japan at war in 1943 – 1945.

It’s only fair for me to issue a brief warning, before you go out and plunk your fifty bucks or so down for this collection, that you won’t be getting rare gems on the level of Rashomon, Seven Samurai, Ikiru or even the more polished and fully-realized “minor” works found in the Postwar Kurosawa set. It might even be stretching things to consider them “diamonds in the rough,” since the young Kurosawa was working in difficult conditions, with limited budgets and was still learning his craft. Still, each of these early films feature moments that I found enjoyable and even amazing when I took all the background stuff into consideration. Distinctive Kurosawa themes and techniques emerge for those who’ve gained familiarity with his mature style, and I was also fascinated to get just a glimpse into some of the cultural artifacts of wartime Japan. Watching these four films over the past week has added to my respect for what Kurosawa, Ozu, Mizoguchi and other Japanese artists had to endure and overcome in order to produce the great cinematic masterpieces of the late 40s and early 50s that earned their lasting fame.

So here are a few comments about each film. I plan to eventually give them all the same individual attention that I have given other Eclipse films in writing my weekly column on this website. But for now, this overview will let you know what to expect.

The two Sanshiro Sugata films, both set in the late 1800s, tell the story of a ambitious young rickshaw driver who comes under the tutelage of Tano, a master of Judo who developed that technique as an offshoot and improvement of the older discipline of Jiu-Jitsu. Of course, Jiu-Jitsu’s teachers didn’t appreciate the new competition and you can easily imagine the tensions that developed in the process of determining which methods were the best. The narrative has some historical basis, but I can’t say with any certainty how much creative license Kurosawa took in his telling. But how cool is it that, after a few basic establishing shots, the very first thing Kurosawa puts on film is a classic showdown between one unarmed and underestimated man and a gang of mean-spirited thugs who consider it their place to teach their adversary a lesson, only to have the tables swiftly and humiliatingly turned on them as Tano shows the superiority of his Judo skills against their bumbling and dishonorable attacks.

Seeing this impressive display, the young hero Sugata applies as Tano’s student and has to go through the customary process of having his youthful zeal, pride and impulsiveness tempered so that he can practice his techniques as they were intended. Highlights of the first film include a judo match between Sugata and an opponent played by the great Takashi Shimura. The bout ends with Sugata completing a devastating toss of his his opponent across the floor and into a wall, as Kurosawa uses a long deliberate pan shot and slow motion to incredible dramatic effect. It’s also fun to see his early use of the trademark “change of weather” to indicate an emotional shift, including a wind-whipped soundtrack that leads into the big finale of judo vs. jiu-jitsu rivals, in an open field of tall grass, no less.

Sanshiro Sugata Part 2 introduces more surprises into the mix as touches of wartime propaganda become quite obvious, in the form of a loutish American sailor who uses sloppy boxing techniques to drunkenly challenge the locals. Of course, he doesn’t fare too well, but that just sets up the introduction of “Killer” Lister, an American boxing champion who wants to show off the superiority of his fighting skills. Of course it all boils down to Sugata stepping into the ring and making his countrymen proud, but I enjoyed getting a sense of what a Japanese version of Rocky IV might have looked like if it came out in 1945. And that was only the first half of Part 2!

The second half ramps up more martial arts action as the judo master faces a vengeful challenge by a brutal advocate of karate, though again I should warn you, the filming methods and acrobatics on display here are very primitive in comparison to how the martial arts action genre would develop over the next several decades. Some of the flips and other moves are achieved more by editing sleight of hand than accomplished practitioners. But the arc of Sanshiro Sugata’s story functions effectively as a prototype for the many heroic action-adventure sagas that Kurosawa and his students would go on to refine and expand upon in countless ways.

The Most Beautiful, Kurosawa’s second film (made between the two Sanshiro Sugata installments) is the most unusual offering in the set, in that it serves a blatantly propagandistic function, clearly at the behest of a government (and its supporting mentality) that Kurosawa would go on to explicitly refute soon after the Empire was defeated. “ATTACK AND DESTROY THE ENEMY” are the first words you see on screen, even before the title or opening credits; later, we listen to a chorus of high-school age girls who work at an optics factory chanting their vows to “destroy America and Britain” and to teach these same values to their descendants. I hold no grudge toward Kurosawa or even the citizens of that time for such sentiments – that’s just the kind of thing that happens in wars, and watching this militant polemic from “the other side” only increases my awareness and vigilance to do what I can to help my own culture avoid falling into that trap.

The film serves as a kind of inspirational motivator to hard-working Japanese citizens who, by 1943, were being pushed severely to step up production and make further sacrifices on behalf of the national war effort. The girls experience their share of squabbles and setbacks but overall are presented as heroic, selfless, patriotic role models who accept their lot and the challenge to increase their output in such a way as to bring shame on the grumblers or dissenters who might be lurking in the audience. Again, Takashi Shimura makes an appearance, as the factory director, but he’s a minor character compared to the teenagers who steal the show by belting out their militaristic hymns and pointing the way forward through kindness and self-discipline, injecting notes of heartfelt emotion even in service to a cause that history has come to see as horribly misguided and destructive.

The fourth film, and last to be made, is The Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail. It’s definitely the first film I’d turn to in this collection for the sake of pure entertainment, and a clear benchmark of technical advancement on Kurosawa’s part as a story-teller and director. The hour-long movie tells an old folk tale about two lordly brothers who have fallen out of favor with each other, and the high-risk journey taken by the more vulnerable of the two across his rival’s domain. In order to have a chance of completing their journey, the deposed nobleman and his samurai entourage must resort to disguising themselves as poor priests and peasants. The travelers first make the acquaintance of a lone porter, a comical, jester-like figure who reminded me of the fool Kyoami from Kurosawa’s late epic Ran.

When the porter accidentally discerns their true identity, they take him into their company and make their way to a barrier set up to prevent the fugitive’s escape. The bulk of the story takes place at this barrier as the group has to rely on their wits to convince the guardians that they are who they claim to be, not who the shrewdest of their interrogators suspect them of being. Kurosawa concocts a fun and spellbinding piece of costume drama, with moments of tension, humor and exotic charm to draw us in and invite us back for return visits. My hunch is that further viewings and more prolonged consideration of the story will reveal further depths of insight and application.

My bottom line on this set is that unless you’re a confirmed Kurosawa or Eclipse completist, have a special curiosity about Japanese film of this era, or have seen these movies before and know you’ll enjoy them, it’s probably one that you’d want to rent first or borrow from a friend. But if you happen to be one of those folks who griped about Criterion not releasing these films outside of the AK 100 box, then you owe it to Criterion to make good on your side of the deal! And if you still feel like complaining, I suppose you could continue to press the issue about what they plan to do about Madadayo…

Years before Akira Kurosawa changed the face of cinema with such iconic works as Rashomon, Seven Samurai, and Yojimbo, he made his start in the Japanese film industry with four popular and exceptional works, created as World War II raged. All gripping dramas, those rare first films’”Sanshiro Sugata; The Most Beautiful; Sanshiro Sugata, Part Two; and The Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail‘”are collected here and include a two-part martial arts saga, a portrait of female volunteers helping the war effort, and a kabuki-derived tale of deception. These captivating films are a glorious introduction to a peerless career.

2 comments