After last week’s loopy diversion into eye-popping kaiju craziness (The X From Outer Space), it’s time for me to resume my exploration of Eclipse Series 39: Early Fassbinder. The decision I made a few weeks ago to not rush through these films just for the sake of producing a quick and timely review of the set right after it was released has already paid dividends. My initial response was one of cool, detached respect for Fassbinder’s undeniable audacity and startling efficiency… remarkable, but not necessarily likable at first glance. Since then, I’ve found myself warming up considerably to the set after spending more time patiently revisiting each title, getting to know the members of Fassbinder’s stock company and figuring out what to make of the floundering, apparently pointless misadventures that the prolific young director plunged his characters into.

Gods of the Plague was the third and final film that Fassbinder released to start his directorial career in 1969, the follow-up to Katzelmacher (the first of the five films in this box reviewed here). It was followed (after a couple other projects were released) by The American Soldier, and with that film, constitutes the second part of an informal trilogy of homages to film noir that started with his debut Love is Colder Than Death (coming up next in this space.) You might wonder why I covered the films out of sequence, since it would have made more sense to review them chronologically. As it turns out, I’m writing them up in the same order they were released in the USA back in the early 1970s as Fassbinder became an international sensation. But that’s just an unplanned coincidence. I’ve linked each article in this series with a corresponding film on my Criterion Reflections blog, so this one connects with Intentions of Murder, Shohei Imamura’s bleak howl of fury and dismay that excoriated early 1960s Japan for its callous oppression of women. The connection between the two films isn’t probably all that clear or obvious, but they do have a common attitude of fatigued numbness and a reductive approach to sexuality that emphasizes its more animalistic functions, as the characters in each give themselves over to impulses they know are self-destructive in the long run but satisfy urgently felt cravings in the moment. The moral collapse of their respective protagonists generates at least a brief illusion of personal intimacy and connection, but the bonds prove to be not only fragile, but mortally dangerous as they push their partners into increasingly desperate circumstances and inevitable tragedy.

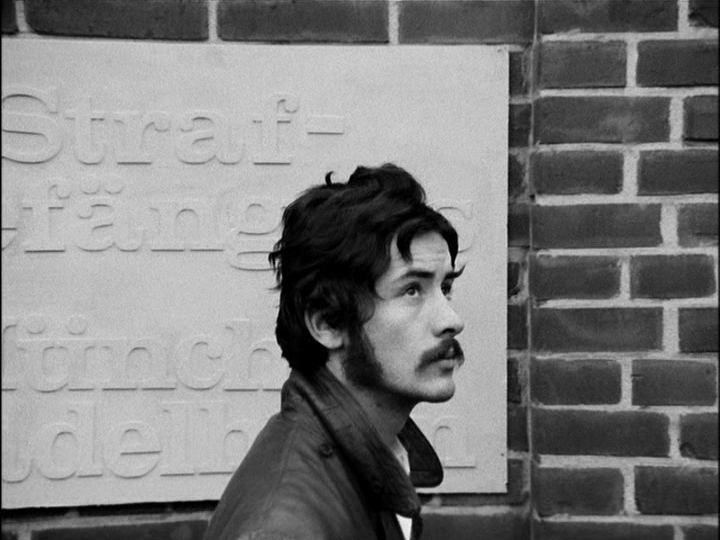

While there is a story being told in Gods of the Plague, it follows such a conventional genre pattern that spelling it out in straightforward terms results in a litany of cliches. Franz (Harry Baer) has just been released from a stretch in prison, and he wastes no time in getting back to his old haunts, for lack of anything better to do. His lover Johanna (Hanna Schygulla) works as a singer (among other duties) in the Lola Montes strip club. Her introduction channels Marlene Dietrich, and in these early tone-setting scenes, we’re abruptly reminded that we’re watching a film made in the nation where so much of the noir and early Expressionist sensibility began, before the talents that created it migrated to Hollywood, before the French appropriated it in the 1950s and reworked so many of its ideas in the nouvelle vague. Now, with the 1960s reaching their bitter end, and the emergence of a New German Cinema, Fassbinder was doing his micro-budgeted best to pump some new life into the husk of a filmmaking tradition that he not only loved, but seemed very intent on living.

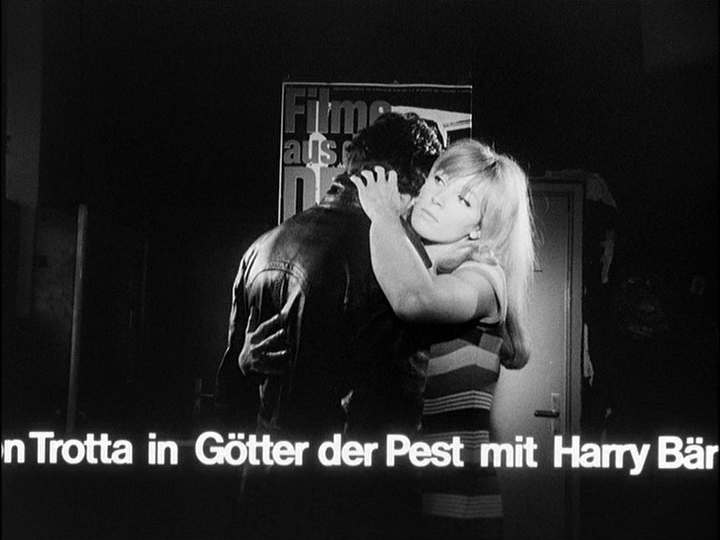

Before Franz reunites with Johanna, he has a spontaneous liaison with Margarethe (Margerethe von Trotta) that sets the central conflict in motion. Two women competing for the attentions of the same man, as basic and primordial as it gets in this kind of movie, but Fassbinder doesn’t stop there. Still, there’s a decided lack of passion fueling these trysts and rivalries. Franz is so wiped out and worn down as to be almost bereft of charisma. He has a handsome look and some will undoubtedly find a degree of sexiness in his fatalistic stagger. Sure, they’re easy on the eyes, but Fassbinder is defiant in his refusal to give us easily lovable rogues or seductively alluring female leads.

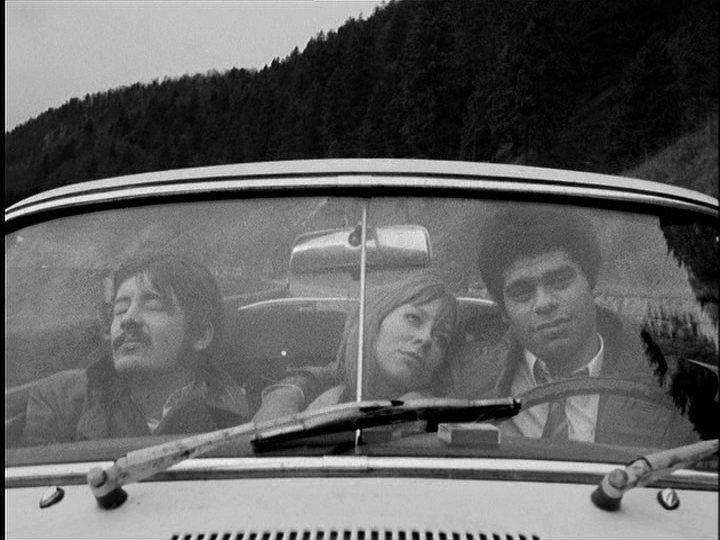

So we trail Franz, Johanna and Margarethe as they circulate through Munich’s grimier quarters, mingling with idle gamblers, hustlers and pornographers, plotting their next moves and staying one step ahead of the cop who’s keeping a wary eye on them, knowing that if he just watches his tabs, some dirty business or other will soon enough develop. He’s assigned to track down a wanted fugitive known as The Gorilla, and his mission is at least partially accomplished by fooling around with Johanna herself as he preys on her vulnerability and lack of orientation in life, all the while blurring the boundaries of his role in law enforcement.

Even when Fassbinder cranks up the volume in the sex and violence department, there’s a morbid somnambulant pall that hangs over what would normally serve to arouse our feelings and galvanize our attention. Apparently, the Gods of the Plague have blighted their victims with a curse of deadly, unshakable ennui.

As the intrigues go through the requisite twists and turns, I found that my mind wandered amiably enough from the insubstantial details of the plot to focus more on the compositions, in particular how nicely so many of the scenes are lit and the moods they evoke. The scenes in Margarethe’s apartment, decorated with an imposing poster of her face looking down upon whoever happens to be in her bed, underscore just how self-referential and media-focused Fassbinder’s world is, as his characters find themselves living relentlessly under the director’s gaze, acting out scripted routines that have had all the life squeezed out of them until there’s nothing left to do but just go through the motions, in search of some facsimile of feeling that will at least break the logjam, maybe even inject an unexpected note of vitality and purpose.

Gods of the Plague does get an infusion of energy upon arrival of The Gorilla (Gunther Kaufmann, abandoned before his birth by his black American G.I. father at the end of WWII and the lover that Fassbinder obsessed over at the time he made this film.) His built-up star entrance (nearly an hour into the film), imposing presence and a nickname tinged with racist stereotypes in the otherwise all-white context jolt us out of any doldrums that we might otherwise fall into due to the film’s languid pace and familiar patterns. Fassbinder himself steps out from behind the camera for a short cameo scene.

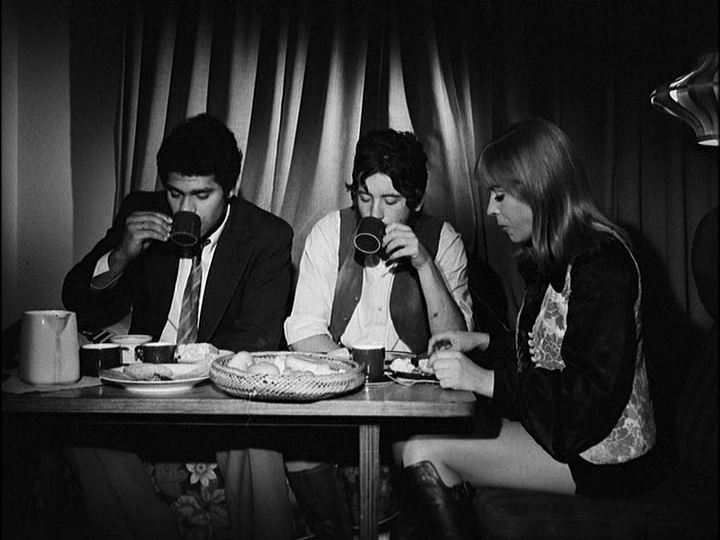

In between the punctuations of plot developments that could, like most of these Early Fassbinder films, easily be compressed into much shorter intervals by more conventional directors, we’re presented with scenes that go on at length for no obvious reason. Characters gaze off into space. They sit at tables, stone silent, picking at a meal, sipping at a drink, or just sitting there waiting for something to happen. Some viewers will find them boring and indulgent, some will appreciate the sense of atmosphere they create, that “settling in with the characters” effect that I mentioned at the beginning of this article. I’ve felt both ways about these films, probably depending on the mood I’m in and whatever competition for my attention span might be occurring at the moment.

Gods of the Plague is most affecting after we turn a patient ear to its anti-theatrical anti-heroes, as they give plaintive voice to their mediocre daydreams of escape to an easier and happier life, down in Greece or some other place where the sun shines. Despite the surface appearances of being young and gorgeous badasses who don’t give a shit about middle class comforts and convenience, we’re subtly informed that they most definitely would settle for something more stable and contented, if they could only find their way there. Instead, life has led them down a path of disappointment and resignation. The tragedy is based on the wastedness of their vitality, and the dreary shabbiness of the world they inhabit, too sprawling and consuming for them to have much hope of foreseeable release.

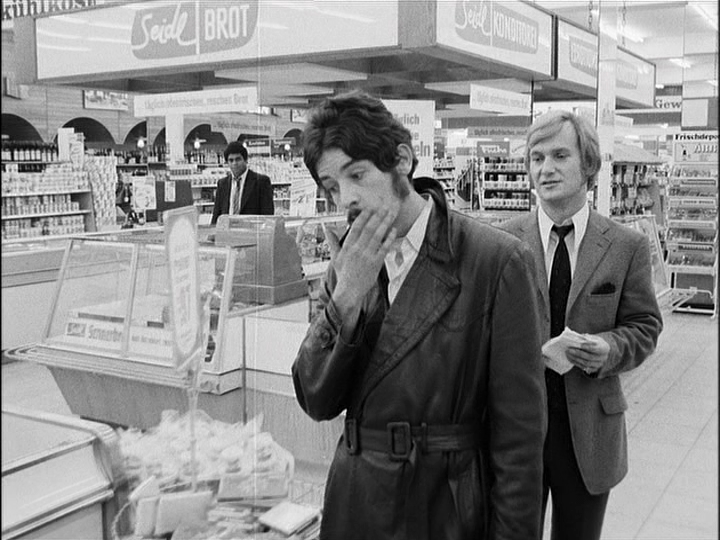

So all that’s left for Franz and the Gorilla is to pull off a supermarket robbery, taking rude advantage of an past friendship with a guy who’s managed to climb a few rungs up the ladder of respectability but apparently has no scruples that prevent him from hanging out with his old criminal buddies once in awhile. It’s a classic scene and stands out in stark distinction from the rest of the film with its brightly lit interiors and gaudy display of unapologetic consumerism.

Of course, the robbery quickly goes bad, mostly on account of Johanna’s (once again) predictable femme fatale maneuvers, as she spills the beans to her boytoy cop friend – maybe it’s to settle the score with her ex on account of Franz jilting her in favor of Margarethe… maybe it’s to ruin Margarethe’s affair, a variation on the “if I can’t have him, neither can you” strain of calculated jealousy. Or maybe it’s just a manifestation of the sleazy confusion that permeates this glum outpost on the frontier of the Cold War. Fassbinder is too smart and too cinematically ambitious to provide anything resembling an on-the-nose explanation of what Gods of the Plague is all about. But he conjures up some evocative scenes, coaxes some degree of odd magnetism from actors who would go on to achieve greater and nobler things in later films, and marks out his territory with impressive confidence for a guy just getting up to cruising speed on perhaps the most incendiary streak of guerrila film-making we can track over the past fifty years.