So in my strained effort to link titles in the new Eclipse Series 39: Early Fassbinder set with films that I’m reviewing on my Criterion Reflections blog, my original plan was to follow up my review of Seijun Suzuki’s Gate of Flesh with Beware of a Holy Whore. It doesn’t take too much thinking to see the connection: Gate of Flesh is about a group of prostitutes in post-WWII Tokyo… holy whores… all pretty obvious, right? Sure, except that Beware of a Holy Whore isn’t really about prostitution in the way that the film’s title seems to indicate, and since it’s the last movie in that box, I’d rather not cover it so soon in this series. So instead, I’ve chosen Katzelmacher, the second feature that Rainer Werner Fassbinder ever made, and as it turns out, quite suitable companion viewing to Gate of Flesh, despite the two films taking radically opposite approaches to the visual compositions used to tell their thematically related stories.

The title of Katzelmacher comes from a German ethnocentric slur, a derisive label applied to foreign immigrants who are typically regarded as filthy, stupid, lazy and a general drain on society, deserving of contempt, if not outright violence simply for their insolent presence in a land where they’re not at all welcome. Watching the first half of the film, one wouldn’t have any idea why Fassbinder stuck it on this production, which he scripted, directed and also edited (under the assumed name of Franz Walsch.)

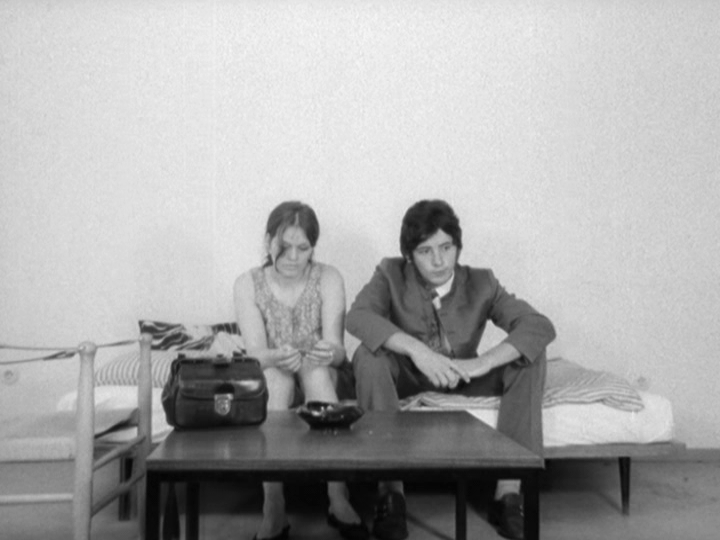

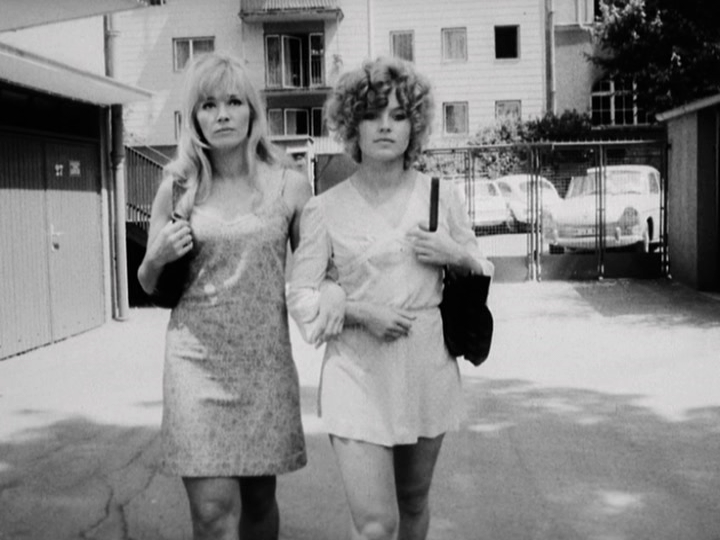

That’s because everything we see involves a cluster of young adults whose days consist of little more than hanging out on local sidewalks, at cheap bars or on each others sofas, griping and muttering and bickering aimlessly with each other, about nothing especially compelling or dramatically significant. Bored or frustrated lovers trade barbs about their partners inadequacies, money problems and thwarted ambitions stir up their share of strife. A pervasive air of tedium and trivial gossip hangs over just about every conversation. Perhaps there are enough raw commonalities between the characters onscreen and the usual challenges and anxieties that most people in their twenties grapple with in any culture to create a sense of identification and sympathy in some viewers, but I can’t say with confidence that those presently living in such circumstances will necessarily enjoy or embrace this cinematic experience. But some will! For the most part, most everyone you meet is floundering through life, none especially admirable or inspired in their response to its demands. I suppose they are all suitably hip and attractive, in their own way.

And because this is Fassbinder testing limits and holding up a mirror to the disillusionment of late 60s German youth culture that he sees all around, there simply has to be a generous dollop of sex, debauchery and vulgar humor tossed in every so often, just because he can. These spikes of action and intensity serve to break up the persistent and accumulating ennui of the film, surely in a realistic echo of the function that such activities served in at least momentarily disrupting the monotony of characters like these that Fassbinder knew quite well and captured for posterity.

These screencaps I’ve included here are representative of a good 80% of what a viewer sees throughout Katzelmacher‘s meandering 90 minutes. Characters positioned directly opposite the lens, almost always side by side with each other, idling away the time, waiting for something indefinite to happen so that they have a reason to move on to wherever they’re headed next.

A closer analysis than I see fit to provide here could spell out the interwoven web of relationships between the three men and the three women that make up this clique. If you want to read something more in depth about this film, Jonathan Rosenbaum composed this excellent review back in 2008, which contains some quotes from Fassbinder explaining his intentions and insights on not only the characters but the film itself – the influences that led him to make the movie at a very pivotal and early point in his career, shortly after his first film Love is Colder Than Death had stirred up so much hostility, way before the name Fassbinder meant something important and worth taking seriously, regardless of how off-putting it might be at first impression.

As often happens with groups that are a little too inbred and deprived of sufficient stimulation from the outside world, Katzelmacher’s subjects are unduly rocked back on their heels when Yorgo, an immigrant Greek laborer unexpectedly shows up in their neighborhood. Yorgo is portrayed by Fassbinder himself, a simple man who knows just enough of the language to express his most basic needs, but is oblivious to the rude insults and mockery that his supposed friends openly express right in front of him as they clink glasses of beer with each other. Arriving as he does from the sultry Mediterranean climate, the German natives imagine him to either a rank subhuman or a sexual dynamo, or probably both. That poses problems for the women in their group who befriend him – Elisabeth, the cranky bitch who decides to rent one of the rooms of her apartment to him since her deadbeat boyfriend Peter can’t find a way to bring in any money, and Marie (Fassbinder’s muse Hanna Schygulla who’s featured in four of the films in this set), who winds up feeling a romantic attraction of sorts to this quietly sensitive, soft-spoken outsider.

The set-up of Yorgo’s innocent injection of earnest drive and determination to improve himself through honest work gives Fassbinder the opportunity to expose the hateful xenophobia that still characterized so much of German bourgeois culture decades after World War II had revealed just how destructive such attitudes could be. Of course, the director is not so pedantic and heavy-handed as to try and forge some kind of moral “lesson” delivered in thick, unmistakable terms. His use of subversive irony and stinging dialogue gets his point across more efficiently and effectively. Beyond their common elements of cheapened sex and brutally casual, senseless violence, it’s that scowl of protest, an expression of profound disappointment with what his society has allowed itself to become in the aftermath of its fatal and foolish world-shaking aggression, that connects Katzelmacher with Gate of Flesh, at least in my thinking. Those who are much more familiar with Fassbinder’s career than I am find this film to be a condensed expression of themes and narrative strategies that he’d continue to develop over the course of his prolific but t00-brief career. It took me a couple of strolls through the neighborhood to adjust to its vibe, but now I think I’ve found my place on the stoop. I just hope they don’t decide to gang up and beat me down because I don’t quite fit in.