So here I am again, back to working my way through Eclipse Series 39: Early Fassbinder. This is my fourth review from that set, this time focusing on the oldest of the bunch, Love is Colder than Death. Rather than proceeding in chronological order with these films, I’ve waited this long to cover it because I’m linking each post in this series to a corresponding entry on my Criterion Reflections blog. Some of those threads of connection have been rather arbitrary and tenuous, I admit, but in this case, pairing Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s feature debut with Jean-Luc Godard’s Band of Outsiders, the match is spot on. It hardly makes a difference whether Fassbinder consciously chose to emulate Godard’s tribute to B-movie gangster films with an homage of his own, or if the numerous similarities between the two films are simply coincidences attributable to the larger formulaic themes of the genre they both drew inspiration from. They’re a complementary pair that make for a great double feature of two impressively prolific and talented cinema visionaries.

Though Fassbinder’s eventual legend as one of the great auteurs was anything but assured or even suspected at the time he released Love is Colder than Death, those close enough to him in the underground theater scene in late 1960s Munich recognized something unique was going on with this guy. Like Godard, Fassbinder spent the formative years of his young adulthood attending the cinema on a daily basis, but instead of becoming a film critic, he poured his energy into acting, eventually establishing the Antiteater, a experimental troupe that lived out its radical avant garde ethos on and off the stage. Fassbinder tried his hand at just every aspect of production – writing original scripts, provocatively adapting classic texts, directing, acting and more, dabbling in 8 mm short film production as well. He proved to be a sharp student, creating a boldly assertive first feature that premiered at the 1969 Berlin Film Festival. The cineastes and sophisticates gathered there weren’t very kind to the novice director, but Fassbinder apparently didn’t mind a bit as he absorbed their chorus of taunts and whistles. He had a lot more tricks up his sleeve and this was only the beginning. They’d be eagerly queuing up to celebrate his latest cinematic transgression soon enough in the months and years ahead.

Fassbinder’s audacity was a hallmark from the very first scene. After crediting himself for script and direction, we see him blandly sitting in an armchair, smoking and reading a newspaper, minding his own business. Nothing happens for several moments, the most static “nothing” of an opening scene one might imagine. Then a man walks in, brusquely asks him for a cigarette, jostles the newspaper, gets his ass kicked in short order, no words are spoken. No explanation needed.

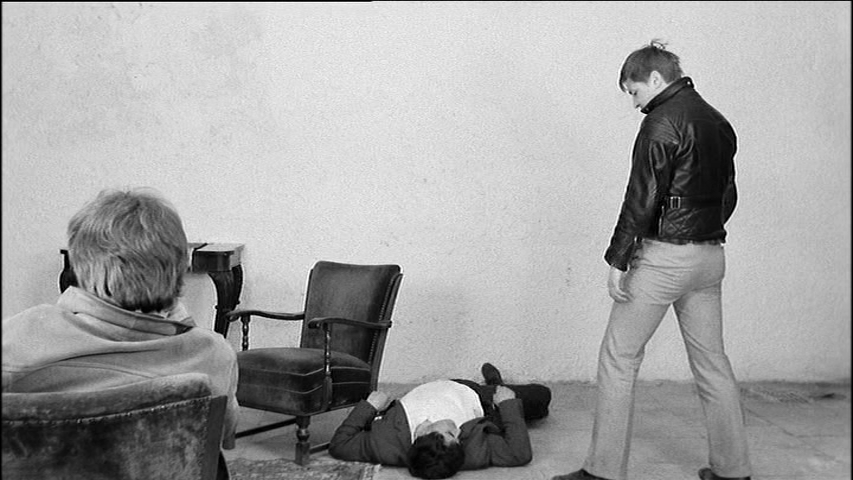

But still, Fassbinder’s character (a small-time thug named Franz) has crossed a line. Franz is taken into custody, not by the police, but by the shadowy enforcers of a group called the Syndicate. They want to recruit Franz to be on their payroll – they like his brutal, aggressive temperament, but Franz doesn’t take orders. Fine, they’ll just give Franz the beating he deserves, leaving him bloodied up on the floor with something to think about the next time they come calling to request his services. The original heckler re-enters to bum that cigarette he never got, that initiated this whole sequence. Franz comes to just in time to grab the guy’s wrist and spit in his face. Franz remains sullen, defiant, dead set on doing things his way, whatever damage that stubbornness may inflict on his long-term well-being. Whether he knew it or not, Fassbinder was encapsulating his life and career in that short but languidly paced opening scene.

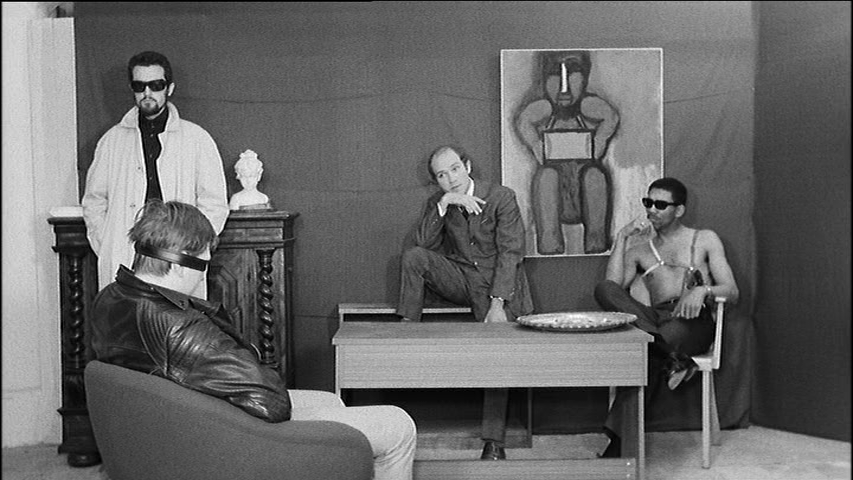

The stark minimalistic set design and lack of any establishing context give Love is Colder than Death‘s initial 15 minutes or so a strange, dislocated feel, as if we’ve been ushered into some kind of existential limbo, vaguely familiar enough for us to comprehend the dynamics of its brutal power play but uncertain what to make of it all. Characters enter and exit into unknown off-screen space, referring to girlfriends and pasts in a world that may or may not have some tangential relationship to our own. Franz makes the acquaintance of Bruno, a hitman with an assignment of persuading him to take up the syndicate’s offer. Franz isn’t ready to yield, but he does give him the address of an apartment in Munich – at last, a recognizable location, the story is reality-based after all! – which he memorizes for future reference.

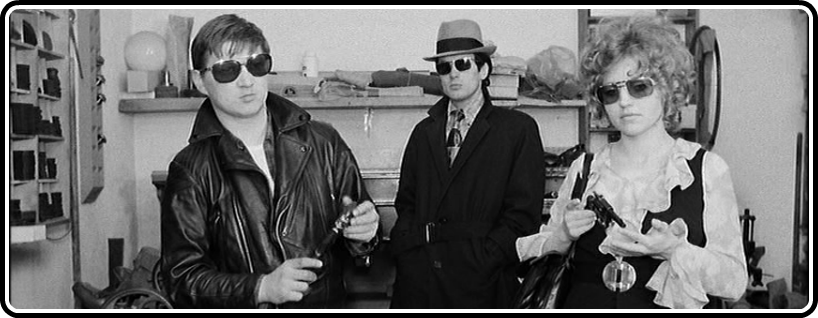

Though the analogy is not exact, in Love is Colder than Death, Franz’s girlfriend Joanna echoes the Odile character (who also had a boyfriend named Franz) from Band of Outsiders. Who’s more scrumptious to gaze upon, Anna Karina or Hannah Schygulla? That debate could easily go on for awhile. Odile is younger and rendered much more innocently, whereas Joanna, despite her rough equivalence in age, is much more sullied by the grim experience of her life as a prostitute deeply immersed in the criminal underworld that for Odile is just a naughty schoolgirl fantasy. There’s also the opacity of Joanna when it comes to her ambitions and motivations. We don’t really get to see much beyond the surface here. The main divergence in this respect between Fassbinder and Godard is that the former wasn’t nearly as obsessed with his lead actress as the latter most definitely was, resulting in a lot less focus (visually and psychologically) on the woman at the pivot of this film’s romantic triangle. But then the same could be said of every other character in this film. As caricatured as the Band of Outsiders are in their archetypal functions, they seem unfathomably complex and layered in comparison to the ciphers we’re presented with in Love is Colder than Death.

Slowly, the elements of a story begin to congeal over the course of a leisurely half-hour first act that’s generously padded with seemingly pointless long takes. A 3 1/2 minute uncut rolling verite shot of Munich streetwalkers under cover of darkness is notoriously indulgent, and not nearly as interesting as it may seem reading about it here. But eventually Bruno makes his way to Franz and Joanna’s apartment, where he takes on the Arthur role in Band of Outsiders as the seasoned criminal who easily cajoles his new accomplices to plunge neck deep into an escalating series of crimes. Again, Love is Colder than Death quickly outstrips Godard’s film, which basically just chronicled one robbery gone wrong, in both the frequency and the brutality of its capers. What a difference five years of cynicism, a generational hand-off and a cultural shift from France to Germany can make.

As a performer, Hannah Schygulla also seemed a lot more relaxed and generous, shall we say, in her readiness to put her full range of attributes into her work. Even though a melancholy hollowness hangs over the couplings that occur every so often in this film, the eroticism on display is more palpable, less coquettish than what Godard asked of his wife Anna Karina (or conversely, what she was willing to give.)

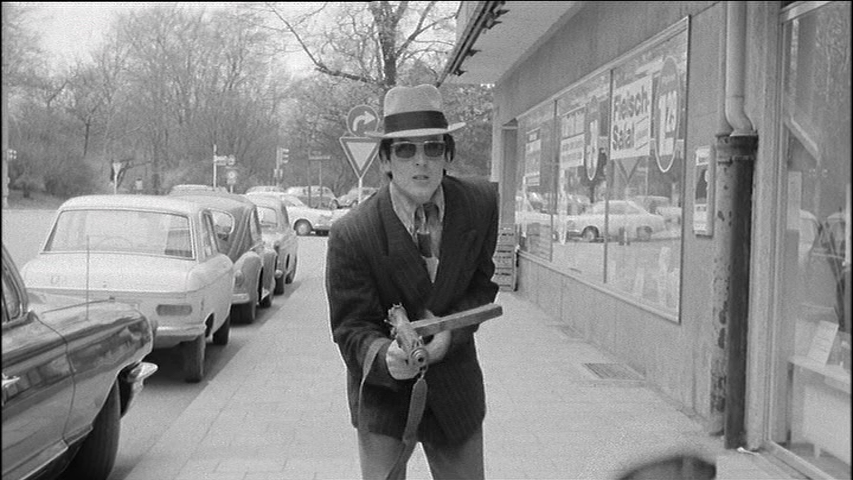

As Love is Colder than Death progresses, we see Fassbinder moving further and further away from the austere white-walled rooms and second-hand furniture that must have borne a striking resemblance to the stage sets that the Antiteater collective used. He takes the camera into cafes, pawn shops, even outdoors, using dollies, tracking shots, low and high angles, each scene giving him a chance to practice new techniques and test out different ideas. Whatever brilliance is on display here isn’t the result of refined skill so much as its the sheer confidence of Fassbinder’s unorthodox delivery.

Also surprising is Fassbinder’s decision to go with the 1.78:1 widescreen ratio, the only film in this set that isn’t shot in 4:3. He uses the stretched out format effectively in the later scenes, including an sonically dissonant long take stroll through the supermarket that spies on the shoplifting Bruno and Joanna, who once more emulate Arthur and Odile in a casual hook-up while their respective pals named Franz are each left to deal with their problems alone. Like many other ideas scattered throughout Love is Colder than Death that crop up in later Fassbinder works, this grocery store them returns with minor variations in Gods of the Plague, the second leg of the so-called “Franz Walsch” trilogy that concludes with The American Soldier.

After Bruno, Franz and Joanna seal their fate through a series of short-sighted, impulsive decisions, there’s nothing left to do but pull off the big hit they’ve been planning. A joint gets cased… a target is selected… witnesses are disposed of… weapons are prepared… the meticulous arrangements are put in place, discussed and mentally rehearsed. But second thoughts, mixed emotions, bad luck and confusions of lust each take their toll on the scheme, leading to misplaced bravado, faulty communication and plain old dirty double crossing.

The idea is that after this band of misfits makes their big haul, they’ll leave this perpetually overcast and blighted scene, this former war zone still looking to shake off the shadows of an ugly past and a seemingly hopeless future for a place that’s sunny, warm and bright. Someplace like Greece, perhaps, home of the refugee Katzelmacher that Fassbinder would freely adapt from his 1967 stage play as the basis for his sophomore feature. No surprise that Franz and Joanna were looking for a more hospitable environment, even if it turned out to be a vague escapist notion… one can’t help but restlessly stay on the move in endless pursuit of something bigger, something better, after coming to the bitter conclusion that, alas, Love is Colder than Death.