In writing this review, I’m struck by the realization that I just might be giving more time and thought to the importance and lasting value of Beyond The Law, Norman Mailer’s second venture into cinema verite experimentalism, than went into the film’s original conception and construction. As the middle installment of three films included in Eclipse Series 35: Maidstone and Other Films by Norman Mailer, we have a companion piece, maybe even an evil twin, to Wild 90, which I reviewed here last week. The earlier film, released in early 1967, represents the imaginary and sloppily performed interplay of three gangsters evading the cops as they’re holed up in a dingy Brooklyn apartment. A few months later, over two nights in October ’67, Mailer and the same two pals he recruited for Wild 90 (Buzz Farber and Mickey Knox) show up again for another foray into experiential improvisational performance art, this time as ornery cops working in the NYC Vice Squad. Though I grant them all the respect they’re due for packing more entertainment value and situational variety into their follow-up production, Beyond the Law alias Bust 80 alias Gibraltar, Burke and Pope alias Copping the Whip or A Fantasy of the Angels, the Downtrodden and the Dispossessed otherwise known as The Velvet Hand and the Iron Tongue (going by the full title as listed in the opening credits) demands just as much indulgence and patience from today’s viewer as its predecessor. Whether or not it pays off sufficiently is way beyond my capacity to foresee. Still, I can’t help but conclude that the Eclipse Series is the perfect repository for just this kind of peculiar artifact of the cultural upheavals that took place during the late 1960s.

The first evidence of the film’s alternative/underground pedigree comes up at the beginning of the title sequence, when we see the words “AN EVERGREEN FILM, Presented by GROVE PRESS.” Though the imprint may not signify much to some of today’s readers, Grove Press was a mark of distinction back in the day, assuring knowledgeable readers that the work bearing that mark was worthy of inclusion on any self-respecting bohemian’s bookshelf. Grove was the more financially stable entity that took over from a ramshackle enterprise set up by Mailer and co-producer Farber called Supreme Mix, Inc. The combined clout of Mailer’s literary and counter-cultural celebrity, and Grove’s independent distribution network of college campuses, offbeat bookstores and psychedelic head shops gave Beyond the Law just enough exposure to justify the creation of one more film in the same vein. Maidstone was filmed the following summer of 1968, though not released until 1970. I’ll be watching it this week, in preparation for both a new episode of The Eclipse Viewer podcast (to be recorded next weekend) and a written review in this column.

Beyond the Law starts with a meeting of two off-duty cops, Rocco and Mickey, and their two blind dates Marcia and Judy in an anonymous New York eatery. The casual banter and thinly veiled sexual urgency on all sides of the conversation reminded me of Robert Downey Sr.’s exploration of the NYC singles scene circa 1968 in No More Excuses, released that same year – the main difference being that Downey was documenting people speaking on their own behalf, whereas Mailer had set up a flimsy pretext for his actors, including Marsha Mason (here spelling her name ‘Marcia’) along with Farber and Knox, to work their coy pickup magic. This opening basically serves as a cue to lead us into the film’s most substantive sequence, an evening of interrogative grilling involving the two cops, their chief officer, and the dismal riffraff that various police raids and random altercations hauled in that night.

Even though Mailer apparently had ambitions to cap Beyond the Law with erotic and relational ruminations that take place outside the police station in which the first half of the film takes place, the first 45-50 minutes or so are easily the most satisfying to me. In it, we meet some interesting characters, each morally ambiguous and wily enough to hold our attention as we see them trotted through the lineup and pressed to fess up in turn. No startling revelations present themselves, nor are we ever granted the satisfaction of a clean admission of guilt that puts us on a path toward sustained justice. Instead, we get a plausible depiction of the murky ethos that develops between hard-pressed cops looking to gather solid leads and evidence through whatever means they can, and evasive crooks seeking to negotiate that fine line of admitting whatever will get them off the hook for bigger problems and concealing the truth that simply gives too much away.

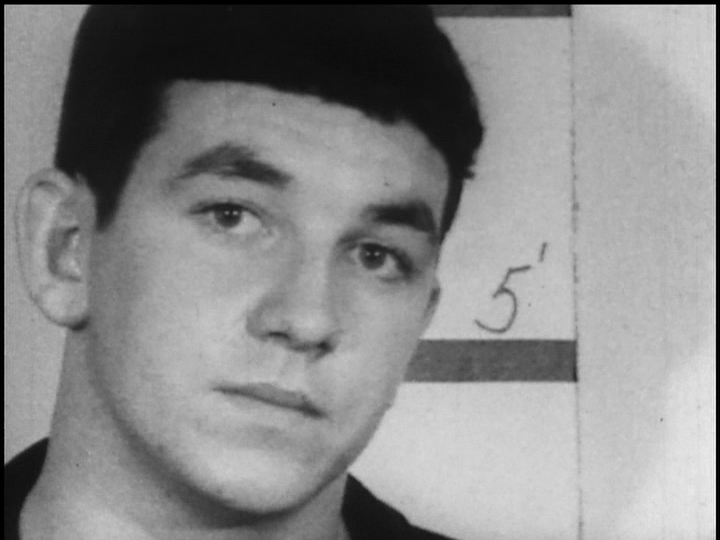

Pictured above, we have a confused young street brawler and Joe Brown, a suspected rapist taken into custody for harassing a woman brought in later that night as a hooker…

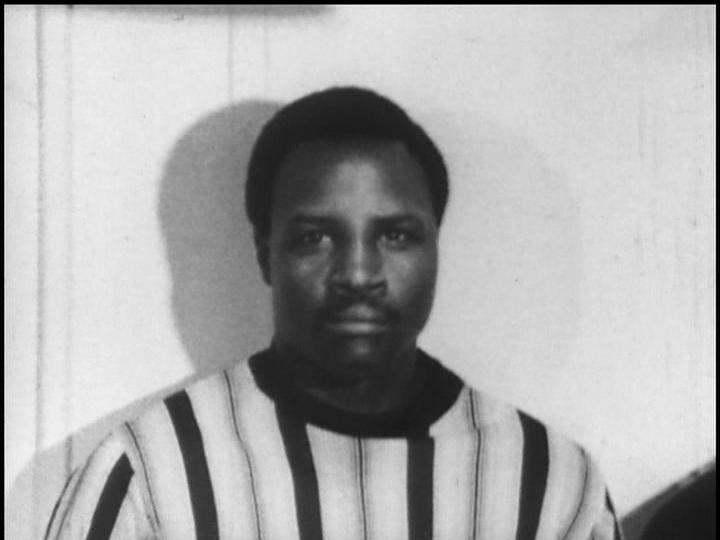

…Mario Rodriguez and Jose Dulce (in real life, Jose Torres, former boxing champion and friend of Mailer who also appeared in Wild 90), each arrested for taking part in a shooting that netted $45 from the victim…

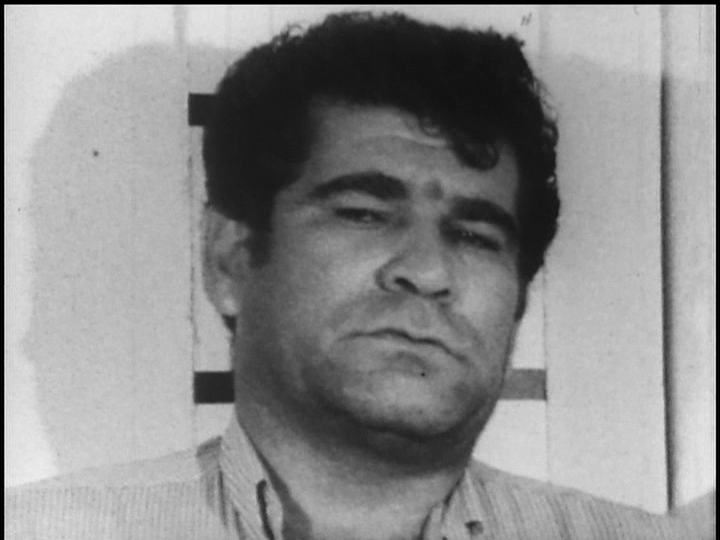

… Jack Scott, wiseguy bankroller of a long-standing floating crap game, and a nameless, shrewdly defiant subway pederast…

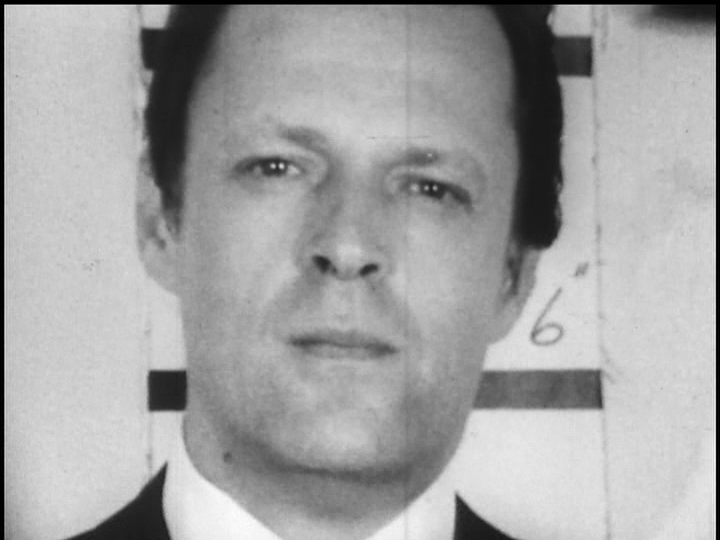

… John Francis, charged with sexually molesting a young neighbor girl by a woman of untrustworthy character, and (not pictured) a confessed ax-murderer who’s all too eager to admit that he killed his wife, but unwilling to divulge a motive or any other reason for the heinous deed. Presiding over this nightly harvest of urban miscreants is Lieutenant Francis Xavier Pope, a grizzled Irish cop played by Mailer with inconsistent rigor as the ethical antithesis of his mafioso Prince character in Wild 90.

Adding to the confusion of a hard night’s work down at the precinct is a subsequent haul of law-breakers: women employed in a “whipping party,” a bordello specializing in BDSM activities that leads to some seductive conversation a little later on, and two scruffy bikers on bad acid trips who push the confrontation beyond verbal exchanges into much more serious physical attacks and weapon-wielding. Pop Corn, the gun-toting hippie freak pictured above, is portrayed by Rip Torn, who’s clearly building up in this film to the full-out assaultive crescendo that will infamously erupt months later in Maidstone.

Mailer trots out all this sleaze and corruption partly to celebrate the exhilarating freedom of uncensored expression (the cussing in this film seems more justifiable, less pointlessly gratuitous than Wild 90‘s torrent of profanity) and partly to tee up pseudo-profound ruminations on human mendacity. Thus, in his interrogation of an attractive young woman brought in on “sodomy” charges:

“People engage evil for several reasons. They engage evil in order to defeat it. They engage evil in order to collaborate with it. And they engage evil because they are apathetic about it. They look for some sensation. Evil, since they are apathetic, presents more sensation than good… It will give me pleasure if you do not turn in the fellow members of your whipping club, because it is possible you are more evil than they are.”

Mailer’s ballsy, grandiose invocation of such weighty themes, and his ability to engage other colorful movers, shakers and influencers like George Plimpton (the tall guy in the upper left above, imitating then-NYC-mayor John Lindsay) in his supercharged explorations of the popular and political culture of his times, makes these audio-visual recordings worth contemplating simply for the stimulative effect they have on our own imaginations, even decades later, even if we ultimately conclude that he’s more of a world-class bullshitter than a thinker of lasting significance. As films, they leave a lot to be desired. Mailer’s confidence in his own artistic invincibility and the apparent ease of just hiring a cameraman (in this case, D.A. Pennebaker) and a few other professionals to act out his half-baked skits convinced him that he could accomplish something significant on the cheap. There are moments in which his lyric and prosaic skills manage to float through the murk to the surface – illuminating bits of dialog, accidental discoveries of evocative juxtapositions as he travels the high-tension wire that runs between juvenile blasphemy and uninhibited truth-telling. But getting to them requires judicious sifting, to the point where less dedicated viewers may simply find themselves drawn to more satisfying pursuits – especially if they are not especially interested in gaining a deeper insight into the wit and wisdom of Norman Mailer, whose influence doesn’t seem to have outlived the sheer force of personality that he delivered while still alive.

As I said earlier, the interrogation scenes speak more effectively to me than Beyond the Law‘s conclusion, in which we see Pope succumb to corrupt desires as he tries to make it with one of the enticing female “whippy-poos” he’d been interrogating just a couple hours earlier. That is, until his wife shows up to blast his seduction to smithereens. By this point, Mailer’s attempt to sustain an Irish cop’s accent and sensibility has become insufferable and most viewers are probably itching to get it over with. Still, there’s no denying that he has a remarkable ability to deliver the bluster in hefty heaping portions – so if you’re among those who’ve come to appreciate Mailer’s expressions on the printed page and want to get a sense of the man and mind behind them, Beyond the Law and the other films in this set bring Norman Mailer to life in his booze-soaked, sweaty, counter-cultural prime.