I suspect that, as is the case with me, the majority of viewers likely to delve into Eclipse Series 40: Late Ray will have to bridge a substantial chronological gap in their exposure to the works of Satyajit Ray. Those of us who have taken the time to survey his earlier films, like the three Criterion Collection releases issued over the past few years or his even older and more celebrated Apu Trilogy, probably haven’t seen much of what he did in that period between the mid-1960s and the three final movies that he made in the twilight of his career. Perhaps in time, Criterion will do us the favor of making those interim films more readily accessible, but in the meantime, I am quite grateful that they’ve found a way to put this conclusive phase of his cinematic output on disc for posterity in an affordable and convenient format for Ray’s expanding cult of aficionados to enjoy.

The Home and the World kicks off my exploration of what the Late Ray box has to offer. Released in 1984, it’s based on a novel by Rabindranath Tagore, the cultural giant of India to whom Satyajit Ray expresses a profound kinship and owes a major debt in terms of inspiration and material. In both its narrative themes and its literary provenance, The Home and the World functions as a book-ending companion piece to Charulata. The two films each focus on the awakening of a more fully-realized sense of individualism and autonomy in the life of a highly privileged and sheltered housewife as she emerges from the tradition-bound shell imposed on her by an oppressive and ancient patriarchal order. And both plots hinge on the tensions that naturally arise when the status quo of a tranquil marriage is disrupted by the intrusion of a deeply felt emotional connection between the wife and a charismatic man who unexpectedly enters the domestic scene.

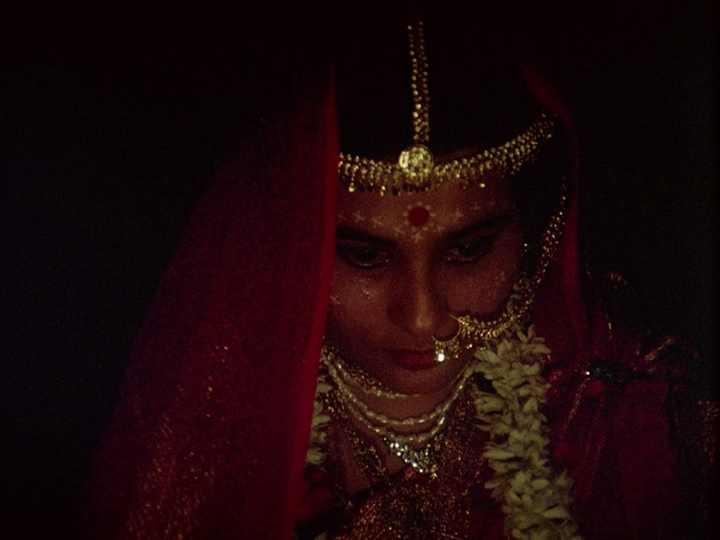

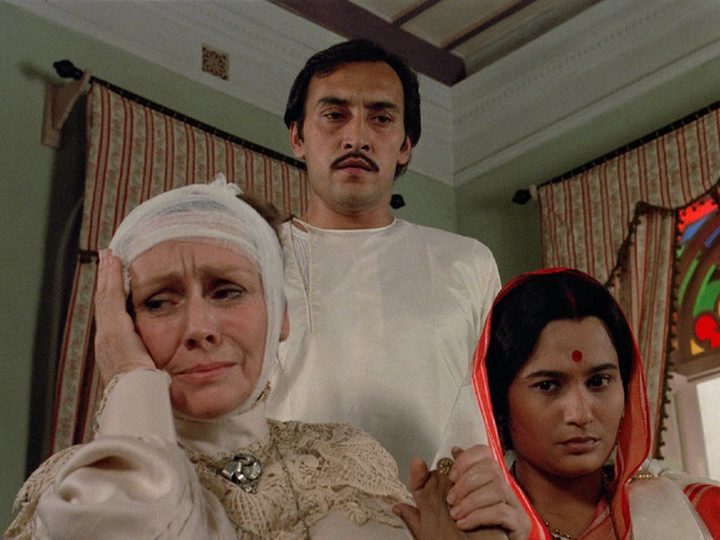

The couple in this film are Bimala, a woman raised to follow the dictates of centuries-old custom that instruct her to live as a subordinate “shadow” of her husband Nikhil, a wealthy aristocrat who’s been educated and persuaded along the lines of highly progressive and Westernized values. Unlike Bimala, who’s content to follow the old ways if that’s what’s expected of her, Nikhil is more restless and idealistic – comfortable in his seat of privilege, but also aware of the many injustices and corruptions that routinely occur in upholding the conventional order of his society.

Nikhil is a free-thinker who has made his peace with colonialism, recognizing that despite the exploitation that occurs under the British governance of India, there are also some definite advantages that accompany the Western influence on that ancient society. Bimala, in this early portion of the film, remains a dutiful wife, unquestioningly trusting and loyal to her husband’s guidance, a perfectly passive student following his lead. The political and cultural debates that provide the context for The Home and the World are again quite similar in tone to the debates that occur in Charulata, and it’s interesting to note the similarities in the 15-year gap between Tagore’s two stories and the 20-year span that separates Ray’s treatment of the same tales, as if each master was deliberately revisiting familiar territory in order to examine the ways in which their complex views on the frictions and compatibilities between Indian and British cultures had evolved.

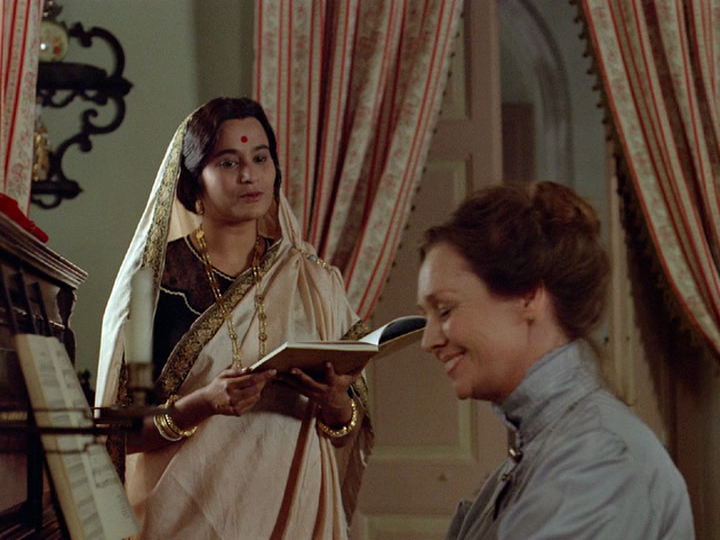

Bimala’s ongoing training consists of lessons in the English language, learning how to sing, play the piano, work an embroidery needle and other domesticated pastimes, all toward the goal of making her an exquisite memsahib, the ideal complement to her husband according to the European standards of how a woman of her status should conduct herself. However, that education is disrupted by strident waves of political unrest, as a local nativist/nationalist movement begins to grow among the populace. Suddenly, foreign influences are looked on with suspicion, or even downright hatred, making Nikhil’s estate and his Western-friendly sympathies the target of militants who want to make a fearful example of those who side with the imperialists.

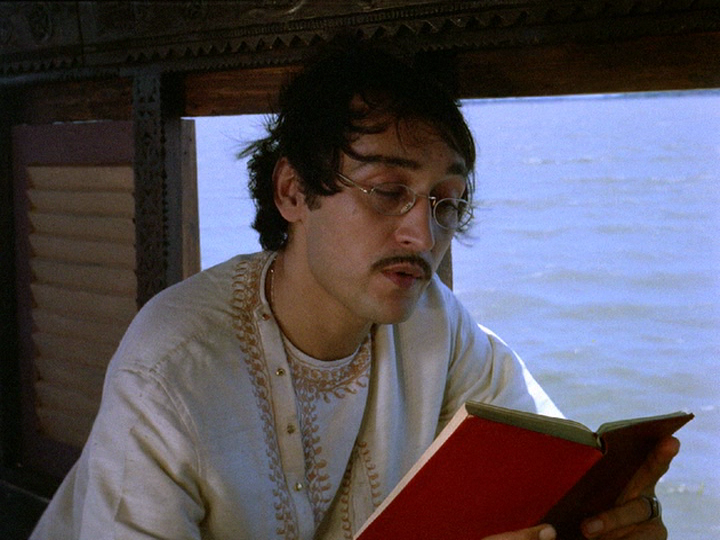

Into this turbulent situation, Nikhil’s old friend from college days enters. His name is Sandip, an ambitious reformer and persuasive activist whose ability to deliver a rabble-rousing speech has thrust him into a prominent leadership role in the radical Swadeshi movement that seeks to ultimately overthrow and expel the British occupation. Because of their prior friendship, and Nikhil’s fearless belief in the power of his ideas, he’s willing to host Sandip in his estate, even though their political values are in stark opposition to each other. And in a commendable but reckless demonstration of putting his money where his mouth is, Nikhil also allows his wife to break the taboo of leaving the confines of her inner apartments, where women of her rank would literally spend their entire adult lives, in order to see and hear for herself as the firebrand Sandip speaks to the assembled masses. From behind the protection of a veiled enclosure, of course.

Nikhil continues to raise the ante, on a wager that may seem at first quite perplexing to viewers who wonder why he would put his wife and marriage in such a vulnerable position, by introducing Bimala directly to Sandip and allowing them to spend time alone together as the organizer instructs his new student in the finer points of Swadeshi ideology. Given Sandip’s all-too-obvious eagerness to get some one-on-one time with the lady of the house, it does seem incredibly reckless at first glance, almost as if Nikhil is deliberately sowing the seeds of an extramarital affair to develop between his wife and friend. But such is the power of his intellectual idealism that he appears to relish the challenge of putting his beliefs about progress, politics, gender and class relations, etc. to the test. Such purity may still seem incredulous to some, but Nikhil’s commitment and sensitivity made him a very sympathetic character to me, even though I recognized that the poor sap was doomed almost from the get-go.

Sandip also turns out to be a fascinating study in human nature – not nearly as sympathetic as the virtuous (and naive) Nikhil, but certainly a man whose values and conduct seem more emblematic of our own times. He’s a mover and shaker, striving for power and influence for its own sake, even as he adopts the cause of populism and empowerment of the lower classes in order to achieve his aims. With no apparent limit to his ambitions as a political reformer and movement leader, he still finds himself quite needy in regards to finding more satisfying emotional connections, and in the hyper-masculine world he travels in, the rare opportunity to spend time in the company of an intelligent, talented and beautiful woman like Bimala has its predictable but nevertheless fascinating effect, basically bringing the revolutionary catalyst to heel as he begins contemplating his own exit from the insurgency in order to pursue more personally satisfying relational pastimes.

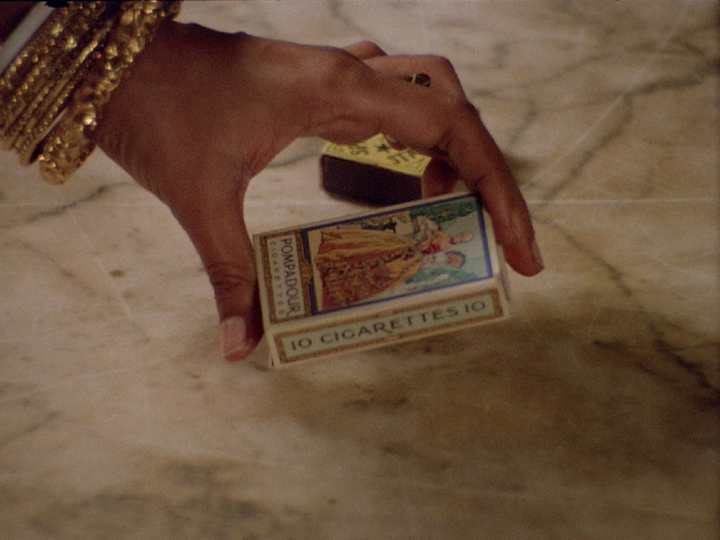

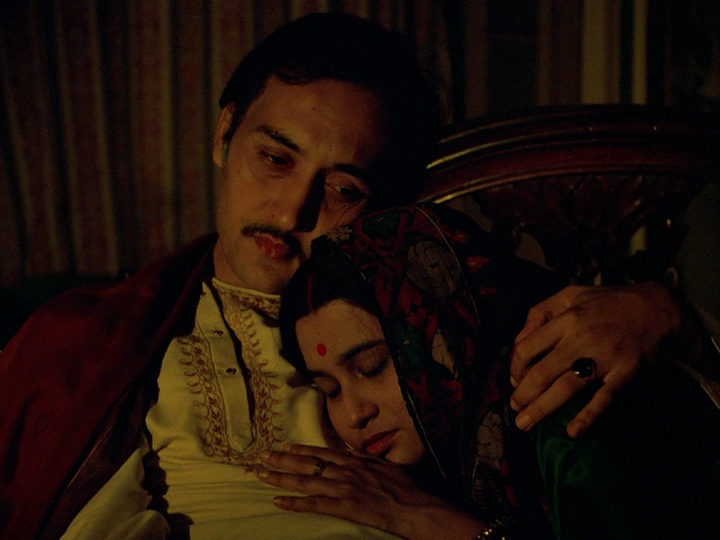

It’s in the subtleties of these conflicts, running the gamut from personal psychological, spiritual and erotic fulfillment to the larger causes of social justice and cultural progress, where The Home and the World strikes its most resounding notes. Ray’s highly refined expertise as a filmmaker has, by this point in his career, settled into a mostly conventional style, with fewer of the magical cinematic touches that made The Music Room, The Big City and Charulata such robustly visual and satisfying experiences. Here, Ray is a bit less daring, and that may be in part due to some of the health problems he experienced while making the film; his son (also named Sandip) had to finish it up under his dad’s supervision. But he still has a few key moments, where he zeroes in on iconic artifacts like those pictured above, to punctuate the narrative in moments that crystallize exactly what is at stake, and the petty hypocrisies that so often undermine our noblest intentions.

This clip, offered merely as a bite-sized sample (with subtitles) of the look and feel of The Home and the World, probably won’t make the impact that Ray intended without knowledge of the story that preceded the moment. But it does offer a hint of the film’s stately pace, which admittedly may drag a bit at times, in keeping with the tone established by other Serious Movies of that early 1980s era, such as Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi. That Oscar-winner would actually make a fine pairing with this film, as they both address similar topics, with Ray’s film providing some very valuable background context on India’s history that many of us who admire Gandhi know next to nothing about.

But beyond all the grandeur and vastness of the Indian subcontinent’s troubled and tragic history, The Home and the World admirably reduces down to a very human and deeply accessible story of conflicted relationships that just happen to be overrun by the conflicts at every level of existence that surround us. In the case of Bimala and the two great loves of her life, Nikhil and Sandip, the alternating impulses of deep connection and profound difference that exist between her and them is likely to resonate with many of us who have experienced similar predicaments in relationships that would otherwise be “just perfect” if this or that element were adjusted more to our liking – only to see reality insist that our wishes remain unfulfilled. So far, this is the only one of the three Late Ray films that I’ve seen, but it definitely whets my appetite for more.