After nearly a year since my last installment in this column, I’m glad to resume my Journey Through the Eclipse Series. There are still a few titles that I haven’t written up since starting this effort back in the spring of 2010, and here’s one of them, spliced into the timeline that I’ve been working on for even longer over on my Criterion Reflections blog. As I alluded to there the other day in composing a few initial thoughts on his 1966 film Violence at Noon, Nagisa Oshima was the front-runner for most insistently provocative Japanese auteur of that time, even though the field was rather crowded with top-notch contenders. Since I want to give this complex, important but most likely under-appreciated film some additional consideration before moving on to other things, I decided to recruit an assistant in writing up this review. Aaron West is a blogger in his own right, author of Criterion Blues, a site that focuses on the Blu-ray titles available in the Criterion Collection. After seeing on Twitter that he had recently watched Violence at Noon, part of Eclipse Series 21: Oshima’s Outlaw Sixties, I asked him if he wanted to engage in some correspondence on this film, and I’m glad that he agreed to join me in writing this review. We’ve had a good conversation via email, and here’s what we had to say about the movie. For clarity, I’ll put Aaron’s words in italics, mine in normal font.

David: Aaron, I figure that you have already seen my introductory comments on Violence at Noon, posted on my blog this afternoon. If not, go look them over!

Aaron: Of course there’s the filmmaking style, the quick cuts, extreme close-ups without framing, almost intentionally jagged and rough, unlike the Japanese masters, especially Ozu, who were very deliberate in the way that everything was framed and blocked.

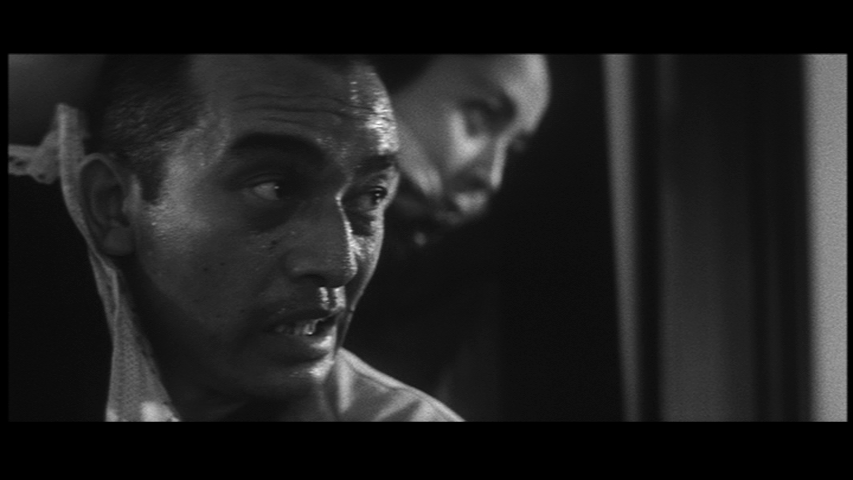

Yes, Oshima appears to have been almost single-handedly (if necessary, though it wasn’t) on a mission to upend all of the conventional methods and approaches utilized by the most venerable Japanese filmmakers that preceded him. There was something obviously quite rambunctious in the air back in those days, since it seems like just about every young director with any serious sense of ambition was pursuing some degree of notoriety based on their status as a provocative, non-conformist rebel. Up to this point, Oshima had established his reputation by using long, fairly rambling but still quite aggressive long takes, allowing his actors ample opportunities to flesh out their characters and dominate the screen through performance. In Violence at Noon, his composition and editing come to the forefront, even though I still harbor a ton of admiration for the actors, especially Kei Sato, who established a fine reputation as a support/side character in many films from this era, but definitely functions as the center of gravity here.

The evil man was a pretty flat character, but the dynamic between the two women was worth examining. They are really the main thrust of the story, and their contrasting views of love, one of which was naive and the other confused. I like how the film language spoke to their uneasiness, with the jump cuts and pivoting camera on the train. You’ve seen far more post-war Japanese films, so you could probably speak to whether this had happened before, but to my knowledge it seems innovative.

I agree that Shino and Matsuko emerge a bit later on as the primary sources of intrigue once the story itself kicks in, but I think Sato’s (Eisuke’s) flatness provides the essential canvas for the two female leads to fill. If he had played (or been directed to portray) his character as more overtly deviant, or shown a more demonstrative affect as a sociopathic monster, the whole narrative would have been undercut. So I want to give some credit here where I think it’s due.

Your mention of the action on the train actually brings to mind the crucial sequence in Kurosawa’s High and Low when the ransom is being paid and the police are trying to capture the kidnapper. Naturally, there are significant differences in the scenes as well, but this presentation of high stakes exchanges taking place in a public, mass transit setting is intriguing, and probably deserves more extended analysis/comparison with other scenes that occur within a similar cinematic context.

* The non-linear narrative. I love the beginning where they flash back to the original crime of the hanging of Genji and fool us into thinking Shino is dead.

* The ending is almost identical to In the Realm of the Senses (which Aaron reviewed here – DB), which is the only other Oshima I’ve seen. Everyone that she trusts or loves is gone and she is lonely.

* It seems there is some statement about post-WWII Japan that I’d probably have to digest some before speaking about it.

Oshima is clearly disgusted with the failure of the radical Japanese Left to manage its affairs and present a cohesive message that the broader populace can latch onto, though I would also extend his critique to the so-called mainstream or “straight” society that is probably too dense or preoccupied to pick up on the plain (albeit revolutionary) truths that the movement proclaims. He’s a relentless provocateur, trying to jostle his audience out of their complacency through whatever violations of the social norms he is allowed to portray on screen. I’m not totally sure he understood at the time just how numbed and complicit his viewers were likely to become through exposure to his work. My hunch is that today’s audience might not immediately pick up on how abrasive and anti-social Eisuke is meant to be, since we’ve practically been coached to feel a degree of sympathy with characters not only like Eisuke but also the two women who “love” him. Especially since none of them are framed as especially villainous or deranged. Their normalcy is at once quite disturbing, but also has the effect of disarming some of the concerns or objections that we might otherwise have as the implications of his behavior and the women’s enabling of his crimes sink into our consciousness.

Aaron’s follow-up to David’s reply:

1. The Style.

Yes, there was a revolution going on, which you referenced in your post. I also just recently saw The Pornographers, which was quite bold based on the established cinematic culture. I think it is also worth mentioning The Sword of Doom, (link to Aaron’s review, and David’s) which also came out early in 1966, and directly challenged the heroic nature of the samurai with its portrayal of Ryunosuke. He can be compared with Eisuke because both characters have a dark soul and a dark heart. They commit inexplicable acts, whether murdering an innocent man at a sacred religious site, or violating a woman that he had saved from death, Eisuke’s thirst for Shino and his subsequent rampage is similar Ryunosuke’s malevolent actions after the thrill of spilling innocent blood. We don’t learn the fate of Ryunosuke because the movie ends abruptly unresolved while he is in the midst of a bloodthirsty killing rage.

In the special features of Tokyo Drifter, the crew that worked with Suzuki admitted that they were attempting to take down the masters a peg. They singled out Ozu, Kurosawa and Mizoguchi. I’m sure Oshima and crew felt the same way, as did Imamura and others. Oshima’s films went further with the graphic nature and frenzied cinematic language.

During the first 15 minutes of Violence at Noon, we are treated to a visual spectacle. The quick cuts, extreme close-ups, and confusing insertion of flashbacks that are not understood until later in the film, are almost the antithesis to Ozu and Kurosawa, who make measured, evenly paced films. As a result, Oshima makes your hair stand up, as you wonder what exactly Eisuke is going to do with Shino. Will he rape her, kill her, or both? The framing of each shot is jagged. The close-ups are tight, somewhat like those of the spaghetti westerns, but they are frazzled. Oshima cuts from quick shots of items in the room, to a part of a person’s body, to the head, to a close-up of dripping sweat, but nothing is framed within the shot. The unnatural filmmaking adds to the intensity of the scene. In ways it is dizzying, and in others it is enthralling. He would use other unconventional styles later in the film, such as jump cuts, swiveling cameras, and few long takes. As the action intensifies, the shot length is shorter and the disorientation kicks in again.

2. The two women are different in multiple ways. One is a teacher and the other a housemaid, so there is a class difference, even if neither are necessarily upper class. Their outlooks on life are also different. The earliest version of Shino’s timeline has her ready to kill herself out of economic misfortune, another irony given how the plot unravels. Matsuko has a much lighter heart and rosier outlook on life and love. We see her pontificating on love’s ultimate ideal. She says that “love seeks no reward” and that “everyone in love are equals.”

In reality this is not the case for either relationship. They are both unequal. Shino does not love Genji. She only ends up with him after he pities her with a loan in order to save her from suicide. They sleep together for three days, and from there it appears that the relationship is loveless. She follows in his suicidal plan, with some resistance, even if she does not understand it. She commits the act more out of servitude than a real desire to die, and she is grateful that her life is saved, until she realizes the violation that involved her resuscitation.

Matsuko’s relationship with Eisuke also began with a violation. He takes advantage of her welcoming nature by pushing her towards sex. This act is initially one of rape, and if Eisuke were not threatened by the phone call, might have flat out raped her. At some point, Matsuko does concede to the relationship and the sexual act is consensual, even if predatory. She settles down and comes to love her husband, but that sentiment is not reciprocated. If anything, Eisuke treats her with scorn. When she learns from Shino that her husband is the criminal at large, she is helpless to do anything, although it is not clear if her inaction is out of loyalty, love, or fear.

3. We should also contrast Eisuke with Genji. Both are involved in the community, but Eisuke is a disruptor, whereas Genji is a popular civil servant. Genji’s love with Shino is not reciprocated, which strangely seems to have to do with Eisuke. Their relationship is far from equal, as Shino entertains the advances of Eisuke, which makes her husband jealous and is the likely reason for his fateful decision for them to end each other. She is basically using Genji as her benefactor. She respects him and is loyal to him as a husband and leader of the community, but her body language shows an attraction to Eisuke.

That loves turns to hate after the violation, but Shino walks a tightrope between the two emotions. She knows that Eisuke is repulsive and has violated her on more than one occasion, but she holds out before she eventually reports him. By her telling the wife about Eisuke and not the police, she is trying to delegate the action to another. Shino rarely takes action of her own accord. Instead she is led by others, such as Genji, Eisuke, and later Matsuko. She feels guilt for being the catalyst for this spree of violence, even if it was Eisuke’s actions and lust towards her that was the ultimate catalyst. Stuck in the role as the victim, she deludes herself into thinking that there was cause and effect, when in reality, her only crime was inaction.

Towards the end of the film, when they are on the train, both women admit that they both love and hate Eisuke. This is perplexing to the viewer, as we see very little in Eisuke that is worthy of love. The film language adds to this confusion. We are as baffled by their feelings as we are disoriented by the moving camera and the extreme close-ups on the their eyes.

I said that Eisuke is a flat character, but there is one scene when he comes to terms with his nature. This is after the initial violation, when he looks down at the water and curses himself as a monster, yet knows that he will do this again. This is his only real weak moment, and it is also the moment when he wills himself towards criminality.

Aaron, you’ve provided some fascinating analysis of the characters, their apparent motivations and relational conflicts. Since this article is already acquiring some extra length, I won’t add much to what you say in that regard, but I’m impressed by your insights. Oshima certainly excels at creating vivid portrayals of women and men whose erotic impulses and tormented emotions drive them into painfully twisted expressions and endlessly difficult circumstances. In the Realm of the Senses was set in a pre-war Japan, whereas Violence at Noon had a much more contemporary feel, with Oshima apparently leveling, as I’ve mentioned already, a harsh critique at the failed communal experiment as one of the primary factors that created such profoundly disturbed characters as the four his film focuses on.

Still, it seems a bit facile to me to conclude that Oshima’s motive here was to simply blame a grassroots political movement that faced enormously long odds of significantly transforming Japanese culture, regardless of the fervor that its more ardent ideologues might have brought to the project. I think he’s either trying to say something about the Japanese psyche – perhaps its warped appropriation of the old feudal honor codes that saw suicide as a handy solution whenever disappointment or dishonor became unbearable – or maybe even more broadly, about the corrupted, confused state of relations between so many men and women in our times, generally speaking. While I can perceive elements of truth in how Oshima depicts some of the guilt-wrenching and stubbornly unresolvable tensions that couples often experience in the most intimate dimensions of their relationships, he’s obviously inflating those conflicts to an extreme, I’d even say insane degree. It certainly makes for compelling cinema, and this is a tour de force, artistically speaking, even if Violence at Noon is destined to leave many viewers cold, confused or repulsed. I think it’s possible to feel any or all of those responses, while still admiring the film. But I’m still not sure where I think Oshima is trying to lead his audience, or what he expects us to take away from the experience. Do you care to venture a guess? In any case, this is your cue to offer your final thoughts. ;) I’ll finish up with a brief conclusion after you weigh in one more time.

I think Oshima is trying to disorient his viewers, shake them up and change their perspective. I think he operates on two levels. He wants people to look at modern Japanese society and culture in one way, and how the traditions and codes of the past are being replaced by new values that he does not necessarily agree with. He also wants people to rethink the way they view film. We’ve all seen the merits of the big three — Kurosawa, Ozu and Mizoguchi — but comparatively, they are relatively safe filmmakers. They are not edgy, at least not compared to the films that we’ve referenced. He is not condemning their style. On the contrary, I think he was just as much a fan of their work as everyone else, but he was also aware of film movements going on throughout the rest of the world. In Violence at Noon, he was clearly influenced by other film movements, possibly French New Wave and American cinema and he used a new, however disorienting, film language. With his 2,000 cuts, he maybe went a little overboard and that makes this a true outlier in Japanese cinema for the time. I agree that it can be jarring and leave viewers cold. Their principles about honor through death, which even then was a fading ideal, are peculiar to Western viewers. Even if it is not as revolutionary today as it was then, it is still a challenging film to watch.

Violence at Noon is a fantastic film, which unfortunately seems to have been left out of the canon of the Japanese New Wave of the 1960s. Perhaps this is because of Oshima’s intensity and radical style. Not to mention, this isn’t exactly an uplifting story. All of the characters are tortured to some degree, and while we do not take pleasure in their tragedies, we cannot help but be fascinated by them.

I agree with your assessment regarding the uniqueness and significance of Violence at Noon. I remember that when this set first came out back in 2010, it generated considerable buzz both from those who were already familiar with Oshima as well as those who had heard about this notorious iconoclast but had little or no exposure to his work. It wouldn’t surprise me if a few of the curiosity seekers who found their way to this set had a hard time finding a point of access – the content is not easily digested, and it might require some adjustment on our part to get acclimated! But I think it’s worth whatever effort might be required. And now that it’s been sitting on shelves for nearly half a decade, and not available on Blu-ray, this collection of his 1960s films seem like they’re on the verge of slipping back into obscurity, so I’m happy to have the chance to promote this one in particular. Now I’m just imagining what it will require of me to give these films their due whenever we get around to covering them on the Eclipse Viewer! (Probably a two-part episode, for starters…)