Very few names have become as synonymous with as many genres as director Fritz Lang. Be it his seminal science fiction picture Metropolis, the definitive serial killer film in M or the masterpiece of film noir Scarlet Street, the director has even, on his CV, arguably the greatest fantasy epic ever made in Die Nibelungen. Inarguably one of cinema’s greatest filmmakers, the director is returning to The Criterion Collection in a handful of weeks with his film Ministry Of Fear, but what about going further?

A Criterion Collection staple, there are a cavalcade of pictures from Lang’s silent period that Criterion could snatch up, and even later on when he jumped ship to the states with pictures like The Blue Gardenia, but if we are in keeping with the director’s influence over entire genres, there is a certain espionage picture that has proven to be as influential a spy picture as any ever made.

Entitled Spies (or Spione), the 1928 picture was penned by Lang and his then wife, Thea von Harbou, and is an early precursor to films like Lang’s own Mabuse films or the legendary Bond franchise. We meet Agent 326, who is assigned to hunt down and bring to justice a criminal hell bent on world domination. As much a “Bond villain” as any we’ve seen in that lauded franchise, he’s the smoking, wheel-chair bound bank director Haghi, who like any good bad guy, dispatches the bombshell Sonja to get the young spy out of his hair for good.

Coming as one of the director’s last silent pictures, and directly following the director’s best film, Metropolis, this is as visually striking a film as the director had made up to that point. A fantastic and innovative screenplay featuring tropes that, to this day, have been aped and meditated upon in various blockbusters and independent films worldwide, Spies introduces things like the spy’s femme fatale into the world of the thriller, making this as important a genre film as there was from that generation.

And it’s also one of Fritz Lang’s strongest directed efforts. Fritz Arno Wagner is his DP here, and the black and white photography is breathtaking. Be it the smoke-filled villain’s lair or the various expressionistic sets designed by the great Edgar G. Ulmer, a director of high regard in his own right (Detour deserves a Criterion release, and he was involved with People On Sunday), this film would go on to influence not only the aesthetic and narrative structure of the entire spy thriller genre, but also things like film noir in its hazy photography and angular art design. Very much a silent, expressionistic film, it’s also symbolic of the films that would come in its wake. Heavy on the contrast, the film uses black and white photography to its best, and with inventive shots (one particularly awe-inspiring moment involves the shooting of a gun, framed perfectly as if Lang were in the midst of taking an actual photograph) the film is smaller than something like Metropolis, but it is just as visually impressive.

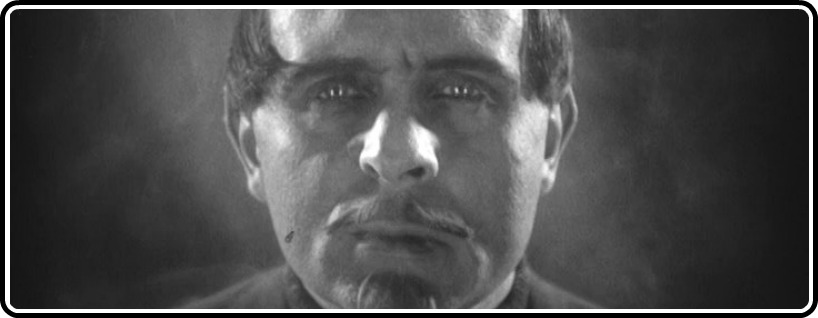

Performance wise, the film is superb. Spies stars the likes of Willy Fritsch, Gerda Maurus and Rudolf Klein-Rogge, and oozes not only style of narrative intrigue. The film is hard to turn one’s eyes away from visually, but with the seductive performance from Maurus, the charming turn from Fritsch and the menacing Metropolis star Klein-Rogge at his most brooding, this film seems to bleed atmosphere from its photography all the way to the evocative performances. Klein-Rogge is particularly brilliant here, giving arguably one of the best villain performances of this time period, if not film history. It’s a performance that shows the actor’s deft range, and proves that while Rotwang may be his best known performance, this man was just more than a one hit wonder. He’s one of the most recognizable faces in all of silent cinema.

Laying the groundwork for entire genres of cinema moving forward, Spies is yet another seminal film in the incomprehensibly influential career of director Fritz Lang. With his films setting the table for films ranging from science fiction epics to brooding film noir picture, Lang once again, with this film, proves that very few filmmakers will leave as much of a fingerprint of this civilization’s art world quite like him. There will never be another Fritz Lang.