Over the last handful of weeks, director Spike Lee has become one of the most talked about filmmakers around. With his remake of the iconic modern revenge thriller Oldboy coming in a couple of months, he’s become even more hotly discussed thanks to his intriguing and polarizing new Kickstarter project. One of the more beloved, if polarizing, filmmakers of his generation, his Kickstarter (for an upcoming fiction project about humans addicted to blood) has garnered him praise by fans (who have gotten the film to roughly $900,000 of its $1.25 million goal) and controversy by those who see him as too big a name to be using the crowd-funding outlet.

However, many of his films prove that while he may occasionally have a bigger budget and some Hollywood talent (I mean, this man did do a film like Inside Man a handful of years ago) he’s also had the energy, mindset and aesthetic of a filmmaker far smaller than his status in pop-culture would have you think. As good a documentary filmmaker as we have today as well, Spike Lee is truly a filmmaker unlike any we have today.

And one film stands as a microcosm of what makes him as singular a voice as film currently has.

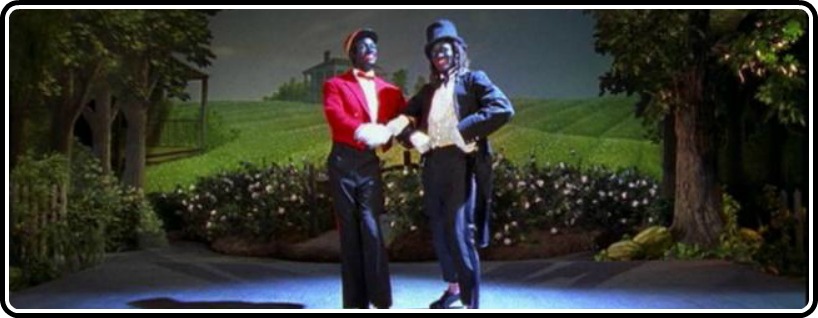

Entitled Bamboozled, Lee’s film stands as one of his most polarizing and yet one of his most aesthetically and thematically enthralling and kinetic. Released in 2000, the film follows the story of a writer named Pierre Delacroix, who is tapped by his TV network to come up with a slate of new shows aimed at an African American audience. The only black writer on the network’s books, he begins losing hope for his position in the group, so hoping to be let go, he begins work on a pilot for a show entitled The ManTan Minstrel Show, a show he believes the network will be so offended by that they fire him. Tapping a dancer named Man Ray and a comedian named Womack, the show is just as over the top offensive as he had imagined, having the two perform in blackface, but what he discovers is that the show becomes a monster hit. This, however, is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to this unsung gem of a film from one of today’s greatest auteurs.

We first meet our lead, the deliciously named Pierre Delacroix, in what may be the most definitively Spike Lee segment of the entire film. A two-ish minute opening monologue setting up both the aesthetic and thematic web that we shall see woven for the film’s 135 minute runtime, the sequence is arguably the film’s most interesting. Ostensibly a reading of the definition of the word satire, the opening sequence is a shot direct to the heart. Shot in startling digital by director of photography Ellen Kuras (best known for her work on such things as Michel Gondry’s Eternal Sunshine Of The Spotless Mind and Jim Jarmusch’s underrated Coffee And Cigarettes) the sequence also uses to perfection Lee’s patented double dolly shot. It’s a shot that Lee has not only gotten down to a science, but has ostensibly become his aesthetic calling card. It also does as much to set the stage for what’s to follow as any opening sequence could.

This is a heightened, almost sermonized sense of reality. With the sun lens flaring every so often in this figure eight dolly shot, his is a beautifully theatrical world that we are about to be thrust into. A breathtakingly visceral experience, the digital photography makes the film look and feel unlike anything Lee had done up to that point, and only comparable to a film like Lee’s last, Red Hook Summer, since. There are occasional moments of aesthetic switch up (an early sequence of Delacroix dreaming of punching his uncomfortably racist boss, for example), but for a film about television to take to a very HBO-style television aesthetic, it becomes something brazenly cinematic. Think something like Soderbergh’s Bubble but even more digitally distilled. This isn’t a glossy picture, but it’s a film that is so angry, so energized and feels like a feature film from a director half Lee’s age. It’s truly a breathtaking piece of work.

The heightened nature of the aesthetic also sets the mood for the world that it attempts to build. Easily one of Lee’s angriest pictures, there isn’t much of a emotional core here outside of the satire Lee is attempting to portray. With a percussive screenplay from Lee, the film neglects to go the straight comedy route and “swings for the fences” going full Mark Twain for the modern generation. Admittedly over the top and disturbingly heavy handed, this film is a blunt instrument of social satire, the film is also viscerally provocative, and so decidedly focused that it becomes as experimental a drama as we’ve ever seen from Lee. The over the top characterization is inherent within the central characters. Pierre is entirely a creation of this character in his distaste of “black” culture, and something like Mark Rapaport’s boss Dunwitty is exactly the opposite. The world is over the top, the characters are over the top and the aesthetic is just as such. It’s truly something to behold.

And again, that’s due to the film’s focus on satire. Stated out right during one of the film’s more intimate moments, the goal of satire is to take these tropes and stereotypes, and find a way to absolutely destroy them. The only way to do this? Distill them to their absolute purest form, like getting something like black actors to wear black face, take them to their logical extreme, and throw these in the faces of everyone who will watch. It also attempts to give us all a sense of history, which itself aids in building this. From previous minstrel acts to a step by step portrayal of the way actual blackface was made by these acts, this sense of knowing history is epitomized by the film’s most powerful sequence, a final montage that comes directly after the absolute apex of the film’s drama. Featuring various films like The Birth of a Nation to cartoons like Ub Iwerks’ Little Black Sambo the film also includes various cameos by people like The Roots and even Paul Mooney. It is this idea, this blending of real history and heightened characters and plot that turns this satire from a simple drama into something so beautifully honest. Toss in discussions about what is art and who has the right to say what is or isn’t, and you have a wonderfully deep and utterly important motion picture.

It also helps that the film has a handful of truly great performances. Led by Damon Wayans in what is likely one of the actor’s greatest performances, the film also stars Savion Glover, Tommy Davidson, Jada Pinkett Smith, Rapaport and even the always entertaining Dante Terrell Smith aka Mos Def aka Yasiin Bey. Glover and Davidson offer up the only real emotional center, as they are the most down to earth characters involved here, while Wayans’ performance will be the one most people take away from the film. It’s a really startling bit of dramatic acting, a theatrical performance caught on film. The film itself carries this theatrical sense of performance across the board. Never really opting for nuance, the film feels entirely like a stage play that just so happened to have been caught by Lee, who found it interesting enough to shoot on the nearest hand held camera.

Overall, while Lee’s picture may not be everyone’s cup of blunt satirical tea, Bamboozled is one of Spike Lee’s many masterpieces. A brutally visceral bit of cultural satire, the film does everything in its power to force the viewer to really take stock of their view of race and ultimately the view of race as seen through the lens of pop culture. However, while the film is inherently and breathtakingly angry film, it not only turns these cultural stereotypes up to their politically incorrect 11, but attempts to give the viewers a bit of a history lesson as well. It is in this brazen mixture that turns Bamboozled into possibly one of Lee’s most interesting and ultimately vital (especially in today’s sociological climate) pictures, a moving look at how modern popular culture isn’t too far off from the types of shows portrayed here. If this is the type of lively Spike Lee that is currently trying to find funding on Kickstarter, then we may be in for something truly special.