Also known as Five Angles on Murder, Asquith’s 1950 investigative thriller will sound more than a little familiar to Criterion fans. In it, detectives Lodge and Butler question the neighbors, friends, and family of a murdered fortune-teller, drudging up conflicted visions of not only the events of the days leading up to her death, but of all the people involved, very much including the, well, woman in question. While certainly not as famous as Akira Kurosawa’s legendary exploration of the fragility of memory and representation (released the same year), and lacking some of that film’s more surreally psychological elements, this is a striking, sort of retrospective-thriller, in which each unfolding piece gets us closer and closer to the truth without getting any more dangerous in the present, but very deadly in the past.

Better known for incisive, if somewhat polite, English stage adaptations like Pygmalion, The Browning Version, and The Importance of Being Earnest (a personal favorite), I was quite struck by Asquith’s dexterity not only with genre here, but also with the medium as well. Ducking in and out of flashbacks, testimonials, and even outright fabrications in the space of a frame (no awkward fade-ins and -outs to mark the past from the present), Asquith treats his entire timeline as one stream. The past may be “over” in a more literal sense, but given the extent to which it continues to affect the progress of the investigation, as well as the way it is being continually reinvented, it cannot be dismissed as a mere flashback or exposition. John D. Guthridge’s editing plays so pointedly with reaction shots, to the point that people in the present sometimes seem to be witnessing the past firsthand. It has immediate, visceral power, especially over the two men who are ostensibly the protagonists, but who have little more function than to move the plot along.

Lodge (Duncan Macrae) and Butler (Joe Linnane) have no real backstory of their own, any personal stake in the outcome, nor any sort of arc over the course of the film. They’re just servicemen, both literally in their profession, but abstractly in getting us from one person to the next. They’re our protagonists, but they don’t actually know anything they’re being told is true, as Lodge notes late in the film when he mentions that, although they’ve met several of her acquaintances, they have only a sketchy understanding of Agnes, the deceased, as each person relates different sides of her that may or may not inform the truth.

This structure gives actress Jean Kent a lot of fun angles to play, from proper lady to seductress to a drunken slut to an almost childlike ingenue. She crafts a glancingly-complete portait of a person without ever giving the sense that we truly know it all, letting all these angles say more about the person painting the picture than their subject. Further, by the time we found out who really killed Agnes with the whatsit in her bedroom apartment, we’re able to see that even that vision might have been something of a perversion itself.

The cast is rounded out by a number of very fine performers, each of whom endears themselves to us so quickly, we hope the murderer will end up being some random passer-by. Surely none of them could have done it, from the sister (Susan Shaw), who’s fallen for the former object of Agne’s own affection (Dirk Borgade), or the maid (Hermione Baddeley), who perhaps too-often enlists the assistance of the pet shop owner and general handyman (Charles Victor), or most tragically, the sailor who desperately loves her, if only he’d stop walking in on her with other men (John McCallum). Each of theirs could nearly be a story all its own, and in all, has the nice effect of asking us to look deeper into people who are otherwise supporting characters in what could just as easily be Agnes’ film. There’s a whole world out there, after all.

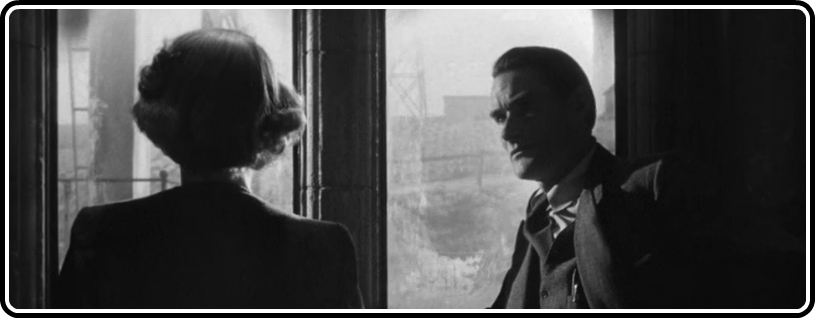

That world is brought to us in high definition on Criterion’s Hulu channel, and looking mighty fine, at that. The deep shadows are not purely servicing the noir style of the time, but deeply necessary, thematically and narratively, to cover up faces, events, and objects. Murder investigations are always about shining a light, drudging up what is unseen, after all, so it’s very nice to have such a fine HD master to really let those inky blacks submerge those more unsavory elements. Grain is finely-managed, and the picture is as crisp as one could hope. No complaints here, in any regard, for this great transfer.

Given their apparent affection for Asquith’s work, I do hope Criterion gives this a full-fledged release. Though its similarity to Rashomon is undeniable, Asquith’s ends are very different here, especially in terms of playing the past against the present and creating a well-stocked ensemble. The other three releases of his films are extremely light on supplements (Earnest and Pygmalion having virtually none at all) that it’s high time we get a closer look at Asquith as a filmmaker, whose talents extend well beyond more theatrical elements into playing deftly with cinematic storytelling (the climax of Earnest is exemplary in this regard, and informs the whole of The Woman in Question). Other supplements regarding the cast would not be unwelcome, either, especially since Kent is still alive, and could hopefully shed a great deal of light on the production of this film and her sizable contributions to it. Beyond that, the film would just look great on Blu-ray.

Until such a day should arrive, head on over to Criterion’s Hulu channel, and give this, and hundreds of other great films, a watch.

To try Hulu Plus, and get two weeks free, click here!