Despite having one of the major film industries in the world, Japan took its sweet time getting to synched sound. Whereas the Americans, Germans, and Brits experienced a near-total conversation by 1930, Japan (and France as well, for ideologically similar, but practically different, reasons) still had a significant industry for silent films through the mid-1930s. Many of the nation’s filmmakers who would go onto be its most renowned – Kenji Mizoguchi, Yasujiro Ozu, Mikio Naruse – were still making silents in 1935, at which point public enthusiasm for the new format outweighed both the affection for and demands from the benshi performers, lecturer/narrator/actors who would lend their vocal talents to silent films.

With more successful directors able to resist the siren’s song, it took one who was a near-failure to bring the talkie to Japan. Having made over forty films between 1925 and 1931 (none of which survive today), Heinosuke Gosho was in a bit of a rut. He hadn’t produced a hit in some time, and Shochiku (his backing studio) more or less gave him one last chance, with a proposed sound film. The technical uncertainty at the time was such that everything he wanted to get into the film had to be done on the set, be in the actor’s dialogue, sound effects, or even the score, which was played live off-camera.

What’s amazing, then, is how breezy and pleasurable The Neighbor’s Wife and Mine is, seemingly barely encumbered by the considerable technical challenges. The film follows a playwright who, under strict deadline, rents a home in a serene country neighborhood to rid himself of distraction, only to find it to be anything but. Not only is his family (children especially) as rowdy as ever, but the area’s numerous animals and, finally, a jazz band, seemingly conspire to prevent any real work getting completed. If the premise seems (perhaps overly) cleverly designed for the new format, that may very well be, but just as American producers turned to the musical to convince audiences of all that silent film was denying them, Gosho uses every scene to mount some argument that this film, and probably countless more, just wouldn’t be as much fun without the aural dimension.

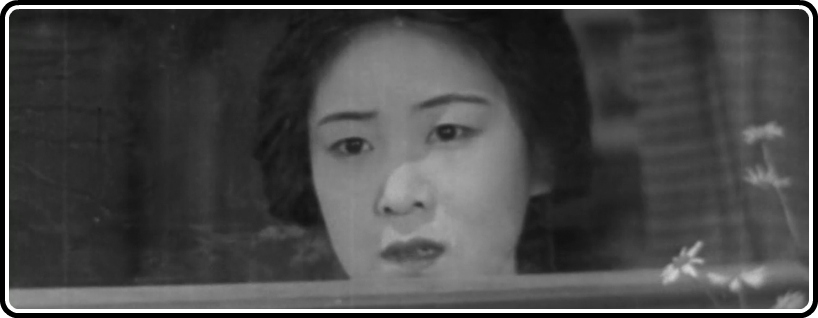

And it is very fun. At just under an hour long, it doesn’t overstay its welcome nor shortchange the rather slim story, which is practically the basis for innumerable (much shorter) Looney Tunes about one character or another attempting to sleep in the midst of unbearable clamor. The playwright (Atsushi Watanabe) is a lazy sort, having already let much of his potential productivity wander away while napping or walking, and his wife (Kinuyo Tanaka, who would go on to star in Mizoguchi’s best films, including playing the title role in The Life of Oharu), limited though she is by the extent to which a woman could wield some power in Japan at the time, is increasingly tired of his many excuses.

Gosho was reportedly heavily influenced by Ernst Lubitsch, and while they could not have portraying two more distinct cultures at the time, there’s something of The Touch at play here. Gosho understands that marriage is as much a partnership as a passion, one given to rather abrasive conflict and uncertainty, but also one that can be strengthened by a hint of transgression. Lubitsch was able to be much more forward in this topic with his make-believe version of a cavorting Western Europe (One Hour With You practically advocates stepping out), but Gosho gets at much the same emotion when the playwright attempts to silence the next-door jazz band, only to be taken in by their music and especially the neighbor’s shapely, lively, striped-dress-wearing wife. “I’m the kind of girl who’s very capricious,” she sings, teasingly.

The playwright doesn’t overextend himself, so to speak, but to see his wife’s reaction upon spotting the two of them laughing, he might very well have. Yet, for whatever the upset, he returns a rejuvenated man, tackling his work – and his marriage – with unprecedented fervor. Gosho knows the society he lives in and speaks to, but, even within that, finds a way to have a little carefree romp. Audiences responded enthusiastically, and he, and sound, became quick fixtures in Japan. Gosho made fifty-seven more films until 1968 (with exactly one hundred films under his belt), and which point he continued his tenure (begun in 1964) as the president of the Directors Guild of Japan until 1980.

Today, he’s not a primary, or even secondary, fixture of discussions of Japanese cinema here in the west, but this film is a strong argument that these conversations should expand their direction and scope. It shows a different side of Japanese cinema in the 1930s, one more populist and entertainment-driven than the melodramas (contemporary or historical) that consume western fascination.

The HD image on Criterion’s Hulu channel does not represent a film in tremendous shape (it may be his oldest surviving film, but it’s on life support), though it does look considerably better during the indoors (presumably studio-set) sequences than the outdoor landscapes. Still, Criterion provides a nice rendering of it. The sound’s a little choppy as well, probably due to the source as much as anything, but it never distracted. I can’t quite imagine, given the shape it’s in, Criterion seeing fit to put this on Blu-ray, but a Gosho Eclipse set would make perfect sense given that line’s mission and output to date.

Until then, head on over to Criterion’s Hulu channel and take a look at this overlooked gem.