In working through so many films of Mikio Naruse last year, one theme that kept recurring was the lingering effects of World War II on families, individuals, and especially relationships. It’s easy to look a the postwar cinema of the United States and be overwhelmed by the amount of dissatisfaction expressed, and the variety through which it was (melodrama, film noir, even musical), but after all, we did win that war. The melancholy of many in Japan could scarcely be called that – outright depression is more fitting. Naruse’s films never let you forget what had taken place in the first half of the 1940s, but Floating Clouds takes that theme to a whole new level, working it intrinsically into a lightly-plotted film soaked in dismay, regret, longing, and debasement.

Like many of Naruse’s films of the 1950s, this 1955 film was based on a novel by Fumiko Hayashi, and, this being their last “collaboration,” it is, perhaps fittingly, their greatest. Yukiko (the great Hideko Takamine) has just returned from her wartime station in French Indochina, and immediately comes to the door of Kengo (Masayuki Mori), with whom she had an affair during the war. As affairs tend to go, a great many promises were made, on which one party or another may not feel compelled to follow up. In this case, Kengo had suggested that perhaps he would leave his wife and marry Yukiko, but his present conscience is less inclined.

Their relationship that follows, as they come into contact over months (if not years), and the one revealed in flashbacks, never seems quite based on love, or even a base sexual attraction, though each are certainly a factor. Rather, there’s a codependence that each feels, a need for the other’s presence long after the desire for it has receded. In fact, throughout most of the film, they cannot stand one another, and with nothing really binding one to the other (and, in fact, great incentive to withdraw from the relationship), the fact that they continue to fall into one another’s arms is beyond curious – it’s a total revelation.

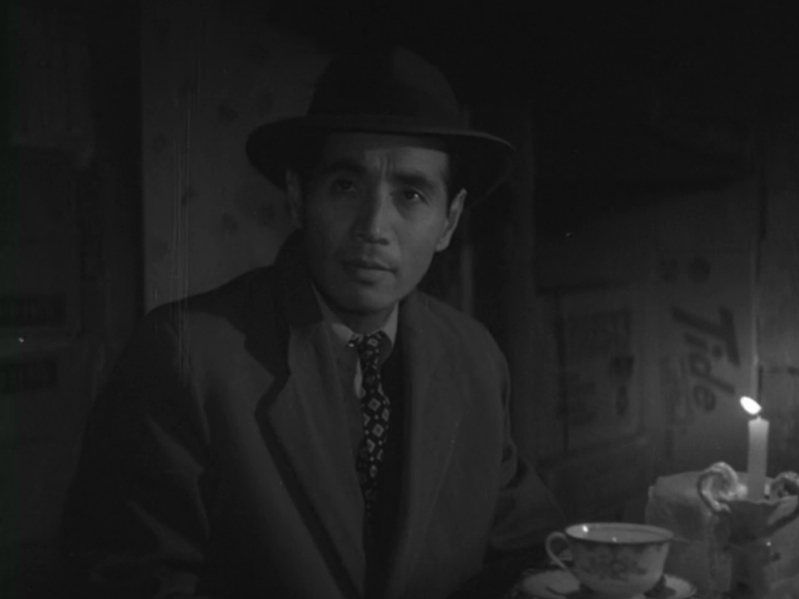

To say Kengo is not a nice man is putting it lightly; it’s not that he thinks only of himself, but that he can’t even think that far. He’s outright insulting to Yukiko when they meet, and hardly gets kinder as their relationship evolves. He’s a slave to his desires and a sense of responsibility for which he expresses no great attachment. This is an immensely difficult character to play, one totally untethered by any internal or external morality, beautifully (yet pitifully) adrift in a way that speaks greatly to the mood of Japan at the time, yet also fulfills a very distinct character purpose. Mori’s rendering of this character is charming without flamboyance, regretful without guilt, and lustful without any real sense of sexuality. He’s a series of contradictions, torn by a nagging sense that he should be anywhere except where he is.

Merely that Yukiko is so fiercely attracted to such a man speaks volumes about her, and the choices she makes when he’s not around are similarly born. That there’s little else to define her seems almost incidental. It’s almost as if her holding onto her wartime love affair is not so dissimilar from the way many hold onto what they see as the glory of war, or indeed the most exciting times of anyone’s life. Her constant longing for him may be as much for him as for a more prosperous time, when she had a job that didn’t degrade her, or was at least an honest living. I adore Takamine’s work in each of her films, but for all the contradictions she plays in When a Woman Ascends the Stairs, the internal conflict in Yearning, the questionable innocence in Carmen Comes Home, this is the most unvarnished, vulnerable, and bold I’ve seen her.

Naruse really became more a visual stylist in the widescreen era, filling every corner of the frame in some meaningful capacity. But his full frame features have a very affecting lyrical quality, as if spurred on by a constant, motionless tracking shot. Adrian Martin called this Naruse’s “cinema of walking,” a sort of gradual journey to an unknown destination, that for whatever the characters do, there are larger forces at play that will push them onward, and it’s not for nothing that Yukiko and Kengo repeatedly discuss killing themselves together, only to back out of it at every turn. This feel is compounded by Naruse’s use of many more locations than typically occupy his films, and a flashback structure that’s dreamlike, flowing, and tied much more urgently to the present than such devices typically are. In her book The Cinema of Naruse Mikio: Japanese Women and Modernity, Catherine Russell writes:

It was not the first time he had used stock shots or flashbacks, but they participate here in a complex narrative structure in which memory and time become much more prominent features than in the spatialized narratives – the home dramas – with which he had become identified. As Hasumi Shigehiko notes, with no ‘two adjacent rooms’ (Naruse’s favored domestic set), the characters and the film lack stability. The couple pass through one or two homes, but they never stay. They are constantly on the move.

To which I would only add, “yet rarely improving.” The new scenery is largely window dressing. Not to say it’s unimportant – as noted, it keeps the characters off-balance, but it never satisfies them in the way they expect, in spite of the sometimes luxurious accommodations. This isn’t exactly on the ostentatious level of an Antonioni film (Yukiko in particular is quite poor, living for a time in a storage room), but the constant movement, and unchanging dissatisfaction, of the central characters did call to mind his L’Avventura, itself concerned with both the state of the soul and a nation at the crossroads, proving, if nothing else, that the ennui for which that film is so noted is not simply a rich person’s problem. The dissatisfaction of one’s soul is unaffected by things of this world, though Naruse wrings a certain urgency from his character’s unprivileged status.

Floating Clouds was the only one of Naruse’s films to make the recent Sight & Sound Critics’ Poll, coming in all the way at 202. I assume everything about that statement is due in large part to the scarcity of his films outside of Japan (at least, being such an admirer of his work, I must believe that), but hopefully its availability here will encourage wider viewership, and hopefully that bit of acclaim would encourage Criterion to release this on Blu-ray. It’d look mighty spectacular, and the HD transfer on Hulu could use a lot of improvement. It’s fairly crisp, but contrast isn’t strong, and the darker grays end up a little muddy, knocking out detail in faces. Further, the audio is often harsh, and could use some clean-up. I don’t want to make it seem unwatchable, as that’s far from the case, and its aesthetic pleasure is still mighty; it just needs some work.

This was posted to Hulu much later than the other Naruse films, and I can’t help but wonder if the condition it’s in necessitated that to some degree. I do hope Criterion takes this film into consideration for further clean-up and a spiffy release, replete with special features concerning the lingering effects of World War II in Japan during the 1950s, and some sort of contemporary interview with Takamine. She died only a few years ago, so I’d have to imagine one exists. Round it out with a commentary from Martin, who placed the film on his own ballot for the Sight & Sound poll.

Until then, a masterpiece awaits you on Criterion’s Hulu channel.

To try Hulu Plus and get two weeks free, click here.