“That film is an outburst of really bad temper….When I made that film I was tired and fed up. And it shows. It’s a nasty, hurt sort of film.” – Ingmar Bergman

At a certain point in a director’s career, failure becomes preordained. A series of successes sets them up for the slightest misstep to be construed a career-ender, and by 1964, Bergman had found such success, and All These Women was more than a slight diversion from what is still today considered a ‘Bergman film.’ Last week I discussed his 1954 comedy A Lesson in Love, and all the ways it was quintessential Bergman despite being more or less a screwball comedy. But there’s almost nothing recognizably Bergman about All These Women. But that doesn’t make a it a failure, either.

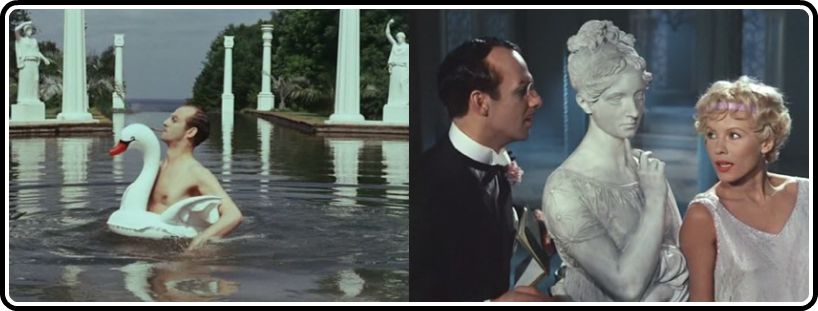

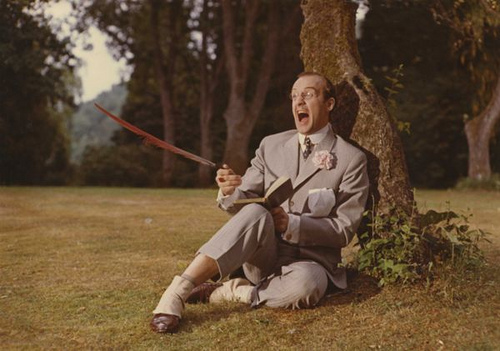

The loose plot revolves around a critic visiting a great cellist with the hopes of writing a biography on the man. When he gets there, he encounters numerous obstacles to his pursuit, not the least of which is his own mismanaged behavior – within minutes of setting foot in the man’s home, he nearly destroys a statue and begins pursuing one of the cellist’s many mistresses, all of whom live with him (hence the title). This isn’t the well-mannered, cleverly written comedy of A Lesson in Love or Smiles of a Summer Night, however; this is Marx-Brothers-level anarchy. And the chaos getting it to screen was not much clearer.

Bergman had served as director of the Royal Dramatic Theatre in Stockholm since 1960, and after completing his unofficial ‘trilogy’ with 1963’s The Silence, he took on the role of manager as well. This dual position would consume his life until he roared back to cinema with 1966’s Persona, and All These Women was the only picture he made between these two points. While a two-year gap between releases seems rather ordinary now, Bergman had directed twenty-six films between 1946 and 1964, and any gap was due only to the fact that he was about to release more than one picture the following year. Sure enough his commitments became overwhelming, and right off the bat Bergman was distracted from his initial goals with the film.

“Our idea was that it should be a film about women, a comedy about women,’ co-writer and frequent Bergman collaborator Erland Josephson would later declare. ‘You never see the cellist. Cornelius, the critic, was not the important part – he was the catalyst. He saw it all and tried to interpret the situation. But Ingmar was very tired, and Jarl Kulle [who is marvelous as the critic] was very gifted, so he took hold of everything, although not of the directing. Ingmar thought he was so funny, so suddenly it was a film about a critic, which was wrong. The intention was really to make a film about all those women, which also was in the title.’

Bergman and Josephson had initially concocted a more episodic film, with a segment for each of the women, each taking place on a different day of the week, who would in some way upset the critic’s plans before turning to pleasure the cellist. Indeed, in the final film, one can’t help but remark on how little the women figure into it at all, save for the initial observation that there are in fact quite a lot of them. The concept for the intended structure is present – it’s stated early on that each woman is assigned a day of the week to spend with the cellist – but it’s never capitalized upon. Bibi Andersson, ever the gifted comedian, runs away with the film, easily the only case member capable of keeping up with Kulle’s admittedly grand acrobatics.

But any of the film’s deficiencies are, more than anything, a sense that it could be much greater than it is, not that it’s a particularly bad or ineptly-made film. Rather, there are several laugh-out-loud moments, many more conceptually hilarious ones, and from a technical standpoint the film is astounding to behold. If the Marx Brothers seem the basis for its comedy, the Archers are its closest aesthetic ties.

Bergman and his by-now-regular cinematographer Sven Nykvist had never worked with color before, at least not together (though his career is typically noted as beginning with their collaboration, he was just as prolific as Bergman before it began). The story goes that the crew was even checked for symptoms of color blindness, and Bergman conducted multiple tests with color to ensure he was ready for it. Nykvist was not pleased with the result, saying it ‘lacked atmosphere,’ but I don’t think atmosphere was called for. Theatrics, certainly, and that is precisely what they achieved. One sequence, as daring conceptually as it is aesthetically, has the lighting slowly transform the scene from sepia to near-Technicolor. That the scene is also an interpretive dance of the sex act, introduced by a title card declaring its place to fend of censors, makes it all the more amusing (one could add another layer to this, given that Bergman staged one of the most graphic depictions of sex for the time just a year before in The Silence, and drew massive crowds for it).

But for all its ambitions, it’s impossible to place this film in Bergman’s career as anything other than an oddity. It doesn’t look like any of his other films, it’s not acted like any of his other films, and it certainly doesn’t explore any of the same themes as any of his other films. It’s a wholly singular work, but the ways in which it stands out are more notable than they are disreputable. I actually found it to be a rather pleasing way to spend seventy-six minutes (even for a Bergman film, it’s very short), and certainly undeserving of the way it’s been shoved aside and hidden all these years. Hell, I was well into my Bergman fanaticism before I’d even heard of the film, and even then it was only because I found it on the shelf at Movie Madness in Portland, sure it must have been misfiled. What kind of film would Bergman make with a title like All These Women? Even the films of his with which I was unfamiliar had recognizably Bergman names like Brink of Life and The Devil’s Eye. But even if I can’t see anything of Bergman in it, I have to say, I really enjoyed watching All These Women.

“I was desperately ashamed of my superficial and artificial comedy,’ Bergman would finally conclude. ‘This shame was instructive but disagreeable. I had had too much else to think about as I had just become director of Dramaten [the Royal Dramatic Theatre in Stockholm], facing my first season without the prospect of pulling out. So I grasped at the simplest solutions. I would have preferred to resign but had committed myself. All the contracts were drawn up and everything prepared down to the last detail. The script was fun and everyone was pleased. Sometimes considerably more courage is required to put on the brakes than to fire the rocket. I lacked the courage and realized, too late, what sort of film I ought to have made. Punishment was not unforthcoming. The whole affair was a dismal failure, with the audience as well as financially.”

All These Women is only available on Criterion’s Hulu channel in standard definition, making one long with each second for its eventual (please?) Blu-ray release. All the problems that plague standard-definition streaming are present – colors are ill-defined and blurry, the picture lacks clarity and depth, and people, particularly in wide shots, are reduced more to figures than humans. As it’s the only way, short of importing, of viewing the film in the United States, one takes what one can get, but even though the audience may be rather slim for it, I do hope Criterion would take it under consideration for a true release. The behind-the-scenes drama and its eventual failure would make for interesting supplements, certainly, and the look of the film is too rich, too unique, to leave it relegated to the land of on-demand viewing.

Often with Bergman’s lesser works, I find them easiest to recommend to people who are already fans, and while aficionados will certainly enjoy learning that Bergman has an anarchic side while linking the visuals to his theatrical background, I’d actually recommend this first to those who haven’t much taken to his more well-known films. If the terribly dour meditations on God and spirituality seemed strained to you, this couldn’t be an experience more removed. That it includes copious amounts of sex, cross-dressing, and even fireworks may serve as icing on the chaotic cake.

Subscribe to Hulu Plus, and get 2 weeks free.