I didn’t intend to make this a mini-series on Robert Bresson, but while waiting in line for Sátántangó (Tarr-gating, if you will) last weekend, the conversation turned to Bresson, and, well, there’s only so long you can wander around certain circles admitting you’ve never seen L’Argent. Especially when it’s so readily available for the watching.

L’Argent was Robert Bresson’s thirteenth and final film, concluding a career that lasted forty years (fifty if you count his 1934 short). That seems rather meager in retrospect, but given the space between each film (mostly two-four years, with occasional six-year breaks), it’s not hard to see many modern filmmakers retiring on a similarly sparse output (though they’ll certainly have a jump on Bresson in age; he was in his forties when he made his first feature). Of course, his limited output was unusual at the time, with many of his contemporaries churning out (at least!) one film each year, but Bresson’s specific, almost confrontationally non-commercial instincts made it difficult for him to find funding, even in France.

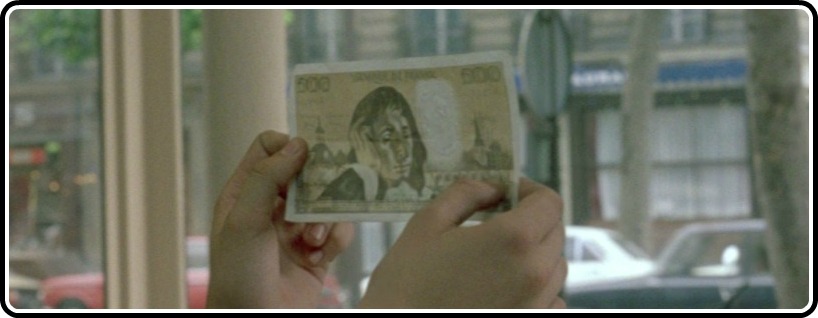

Fitting, then, that the preoccupation of L’Argent is as much money (which is the literal translation of the title) as it is pride. The story begins rather simply, as a young man, Norbert (what a name), in a clearly upper-class family asks his father for some extra spending cash to pay back a friend, a request his father declines. So he turns to another friend, who passes him a counterfeit bill, which they then take to a photo shop to purchase an innocuous item and get some real cash in return. The sales woman doesn’t identify it, but her boss does, and rather than end the matter there, he decides he’ll just pass the bill along. It promptly ends up in the hands of the gas man, Yvon, who is arrested for passing counterfeit bills.

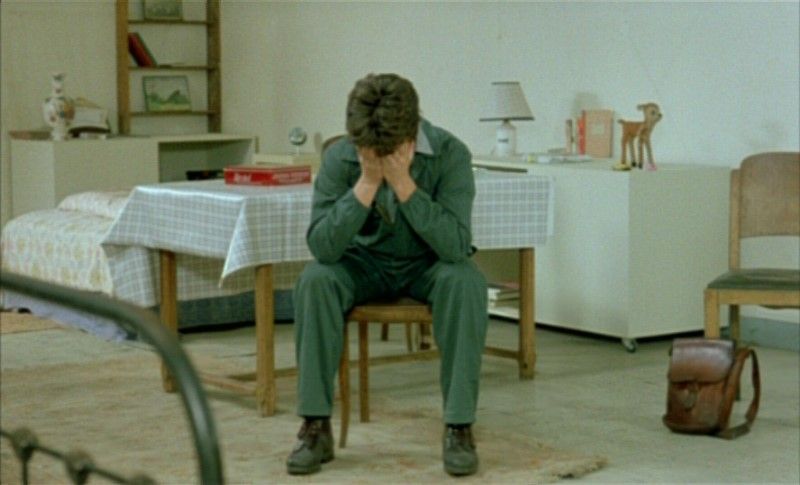

Things, naturally, continue from there, and not for the better. Bresson’s characteristically spare style is in full force here, allowing for few instances of true acting, which coaxes one into viewing this as an account of processes. The “account” part would be accurate, but simply observing the ripple effect of casual greed is merely the first of many layers of L’Argent. The film is also an account of the degradation of self. Yvon’s continual misfortunes are as much a product of his own pride and shortsightedness as they are the circumstances into which he was thrust. At every turn, he takes the first, easiest way out without a thought towards the consequences. By keeping his distance, Bresson allows us to intellectualize this a bit, sympathizing with Yvon while also pitying him.

In some ways, L’Argent is an exploration of how the universal law of energy (cannot be created or destroyed, only converted) applies also to misdeeds. And while the trickle-down theory of economics may not apply to the transfer of money, it certainly seems to be the manner in which the punishment washes. Norbert’s crime is simple theft on the face of it, but because he’s able to go unpunished (first through trickery and later through bribing), somebody has to take the fall. Yvon, a man with few means and even less cunning, is the perfect victim, and so long as none of the responsible parties think too hard about what they’ve wrought, nobody will be the wiser.

This incisive view of economics and class was certainly a viable one in the early eighties, but it has taken on perhaps greater levels of importance in the intervening thirty years. The recent Occupy Wall Street movement was widely mischaracterized as the lower classes’ jealousy of the upper’s material worth, but that wasn’t what it was about at all. It was about the intangible things that money buys; the ability to remove oneself from certain responsibilities and, more pressingly, certain consequences.

It’s as great a film as Bresson ever made, and proof that there’s no reason you can’t still be pissed at the system when you’re in your eighties.

Presented in standard definition on Criterion’s Hulu channel, say it with me now everybody, L’Argent certainly suffers from compression issues, both on one’s computer and through the television. Darker scenes near the end are especially disastrous. On my TV, I got better sense of the picture, as they simply put black bars on either side to maintain the 1.66:1 aspect ratio, while on my computer the image was letterboxed on all sides. Kind of a pain. However, I was rather pleased with the representation of the colors here. L’Argent isn’t The Red Shoes or anything, but the color palette has a certain boldness to it that is nicely replicated.

Given the recent, touring, all-singing, all-dancing (I might have made those last two up) restoration of the film, I really, really hope this means Criterion isn’t too far behind with a lavish Blu-ray edition. It’s been long out of print in the U.S., and has never really received a proper edition anywhere. The one major benefit of the New Yorker release is the Kent Jones commentary, which I hope Criterion would have the good sense to license. Any existing interviews with Bresson during or after this period would also be quite fitting.

To try Hulu Plus and get two weeks free, click here.