Given his reputation as the one of the founders of neorealism, one could be forgiven for wondering, as The Machine That Kills Bad People starts, if you had perhaps wandered into the wrong picture. Perhaps the projectionist mixed up their reels? Sure, the film has already credited Rossellini as the director, but what is this film in which a sentient arm literally constructs the town in which the film is about to take place? What is this joyful narration? And is that a ghost you’re about to see in a few minutes? Indeed, all these things and more are part of the oddest Rossellini film I’ve yet seen, but one which nonetheless speaks to the ambitions with which I more closely associate his work, as I discussed in my piece on his 1954 film, Fear – he is not a neorealist filmmaker, but a genre man who employs neorealist tactics to inform his cinematic world. So just like that film is a neorealist noir, Rome, Open City a neorealist thriller, Europa ’51 a neorealist fable, or Journey to Italy a neorealist melodrama, so too is The Machine That Kills Bad People a neorealist fantasy, almost a fairy tale.

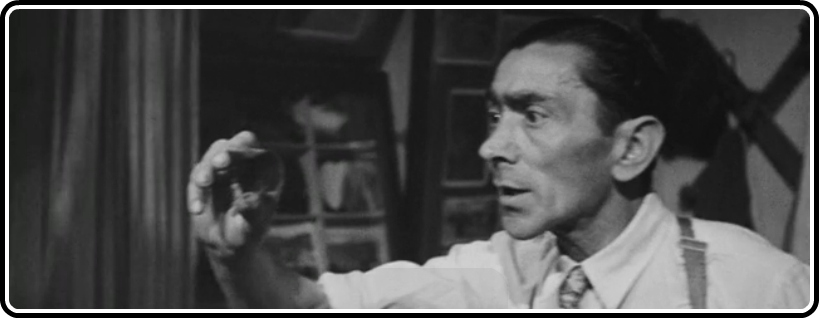

Following a celebration honoring their patron saint, St. Andrew, in a small seaside Italian town, local photographer Celestino is visited by an old man who says he’s that very saint, a claim substantiated by the mysterious gift he bestows to our protagonist – the ability to kill people by photographing an existing photo of that person. Given that his town is ruled by crooked politicians and the even more crooked rich, Celestino finds no shortage of targets who he believes to be eliminating for the greater good of the lower class, and even does some good in the meantime. But before long, he naturally falls into acting purely in his own self-interest, the very pattern he decries in them.

The film makes no bones about its status as a morality tale, even offering a full-blown interpretation via narration at the very end, but Rossellini’s touch, also evident in his wonderful The Flowers of St. Francis, at once matches and counters what could otherwise be a didactic tone. Even given its neorealist touches – location shooting, nonprofessional actors, natural conversation styles – a sense of whimsy and wonder permeates its running time, and the otherwise grim director proves very good at a certain kind of Italian comedy, one which isn’t especially predicated on sharp jokes, but on a humorous air that puts a smile on your face and keeps it there. Rather incredibly, Rossellini apparently began the project in 1948, making it his first after his much-acclaimed Trilogy, but abandoned it. The film was finished by someone else entirely and released in 1952. It’s hard to ascertain just how much of it was him, but the fact that its tone is so thoroughly consistent is remarkable nonetheless.

While certainly not the highest-profile title recently restored by the rather-obviously-named Rossellini Project, I was pleased to find this on Criterion’s Hulu channel, and looking damn good for it. A bit of damage here or there, some variations on image quality during processed shots, and a healthy dose of good, old-fashioned film grain keep this from falling into the ever-preying hands of digitalization, while all of that process’ benefits, from stabilization to sharpening to more defined contrast, are in full effect. I’d even say it looks a little better than the Hulu version of Voyage (or Journey, if you like) to Italy. But that’s just me.

With their recently-announced Rossellini/Bergman box set, it’s hard to say for sure the future of all these “other” Rossellini titles. It’d be hard to imagine them making up a box set of their own (and even then, what would you call it? The Other Rossellinis, Sometimes Starring Ingrid Bergman But Mostly Other People? Not gonna fly), or even shouldering their own releases, but if Criterion didn’t surprise us from time to time, hey, what’d be the fun of all this. This is certainly a film that deserves a brighter spotlight, one Criterion is certainly in a position to give it, and given the almost nonexistent one it currently enjoys, it also has the most to benefit from new supplements and wider distribution. I’d definitely like to know more about its production, and why Rossellini abandoned it, as well as who took up the reigns, and to what extent.

Until then, as always, head on over to Criterion’s Hulu channel, watch yourself some comedy, Italian style.