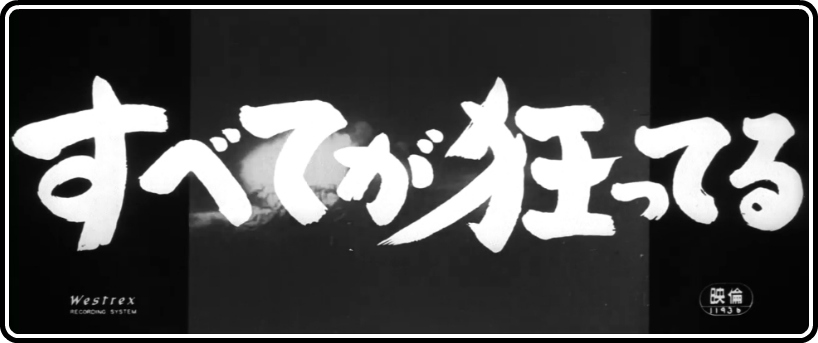

As we’ve discussed previously in this column, Japan was way ahead of other world cinema players in depicting the truly sordid side of youth culture, and with a title as arresting as Everything Goes Wrong, there’s even more to live up to. Seijun Suzuki’s film, released the same year as Oshima’s Cruel Story of Youth, might not be as polished or thematically resonant, but there’s something about its unvarnished, fly-by-the-seat-of-its-pants quality that feels even more vital to the true experience of youth. Suzuki was coming at this as an outsider, already in his late-30s, but seems, even from a distant, totally in touch with the volatile emotions of youth.

Jiro himself isn’t the most pleasant sort, even towards the people he should, by all reasoning, feel more kindly. He’s recently taken up with a young woman, Toshimi (Yoshiko Yatsu), and, like many men before him, goes into the relationship a somewhat timid and petty boy and emerges an overly-confident and petty man. Through a very small timeframe, Toshimi moves from being the one who calls the shots, to something of an equal, to just barely hanging on for the ride, desperate to cling to Jiro wherever he goes. Everything is in flux, constantly changing and (d)evolving, barreling uncontrollably to a fate determined equally by the title and a series of very poor decisions. That Jiro is hardly alone in his jackassery (a few other young men in the film do much worse) is all the more damning of this new generation.

The only time Suzuki settles down is to spend some time with the people of his own generation, who don’t have many scenes all to themselves, but all they can do is sit back, wide-eyed, amused, and slightly afraid at the parade of teenagers who gallop through their lives. It’s easy to see Suzuki using these people as his surrogates, as he was of their generation and, by his own account, took a rather callous and humorous attitude with him through the war, finding many horrors to be bleakly funny, an approach not unfamiliar in his films. Everything Goes Wrong is a lot more straightforward than either Tokyo Drifter or certainly Branded to Kill, and exemplifies in a more cemented way the qualities for which he would go on to be praised – essentially, using a shoestring budget and schedule as a means to experiment and push narrative/aesthetic boundaries. While his more famous films certainly do that, they’re also extremely confident endeavors, and there’s a great pleasure to the journey he’s on in this earlier film to find his own limits of creativity, if indeed they exist. That this is a less accomplished film is almost a given, but for many, it should also prove more grounded.

Everything Goes Wrong is available on Criterion’s Hulu channel in glorious, wondrous, life-affirming HD, and looks mighty splendid. Rich blacks, booming whites, and just a hint of film grain make for a mighty enjoyable, lean 72-minute ride. Suzuki was really a master of the frame, and while this is very much him finding his footing, he still knows how to use it both to the ends for which he was hired (teasing at sex, exploiting violence, and so forth) and to his own artistic desires (which are not exclusive of the former, by the by), and this is a more than worthy avenue through which to indulge yourself.

Criterion has been kind to Suzuki over the years, giving six of his films spine numbers and sliding one into an Eclipse set, so I don’t want to say a full-blown Criterion release is impossible here, and we’ll let ourselves dream for a second. These B-movies are fascinating endeavors, and you really can’t dedicate enough time or space in the form of supplements to the various production concerns, both imposed and voluntary. The stories from the set are often wild enough, but in an interview, Suzuki brought up an angle I hadn’t even considered, which is that a successful B-movie director will take into account how the main feature on the double bill will affect an audience’s perception of his films. Outfits like Nikkatsu, the studio at which Suzuki worked, were fascinating machines, and it’s well worth exploring how that machine worked, and how artists like Suzuki navigated their waters.

Until then, Everything Goes Wrong will be sitting (very) pretty, ready for you to queue it up on the Hulu channel.

To try Hulu Plus and get two weeks free, click here.