David’s Quick Take for the tl;dr Media Consumer:

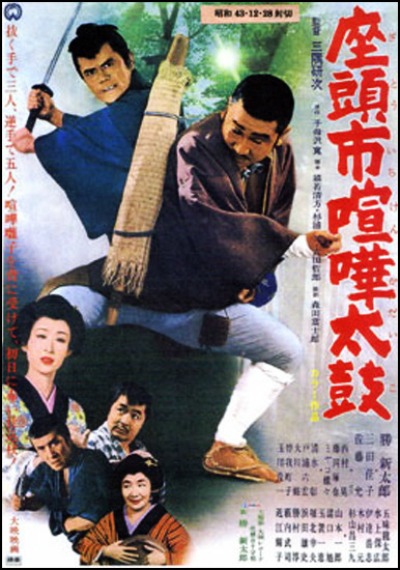

Samaritan Zatoichi, the 19th film in the franchise and the fifth of six installments directed by Kenji Misumi (who started off the series with 1962’s original The Tale of Zatoichi) is a solid entry in the series that I can’t say is particularly unique or altogether distinctive from its predecessors. The aspect that stands out the most is that we get to see Zatoichi functioning in a role usually reserved for his backstory, that of a lethal yakuza enforcer, even though his companions in that early scene don’t seem to have any knowledge of his lethal capabilities. To them, he’s just a blind bumbling tagalong who could have just as easily been left behind. But as it turns out, Ichi is the guy who had to deliver the fatal blow to a young hothead who didn’t pay back his debt to the mob in time to stave off punishment. It’s only when the dead man’s sister shows up a few minutes later after the dirty work has been done that Zatoichi recognizes that he’s been duped into committing an act of gross injustice. This dark set-up serves as an effective platform for yet another variation on the theme of redemption through violence, and the heavy toll that process takes on those who somehow manage to survive its cruel whims of fate. There’s also the peculiar twist of the obligatory gambling vignette, which in this case demonstrates something that I’ve wondered about but has never been explicitly revealed in earlier films: that Zatoichi at least occasionally cheats at dice. He also takes a galloping horse ride (especially perilous due to his blindness) and for no particular reason other than to revel in the absurdity of it all, shows himself to be a master of the carnival arcade ball-toss. One stranger-than-usual sequence shows Zatoichi bound up in a reed mat, about to be tossed into a river – a scene that bears eerie resemblance to similar events portrayed in Silence (though this take is much more comical than the deadly seriousness of Martin Scorcese’s most recent release.) Because of these anomalies, Samaritan Zatoichi isn’t the ideal introduction to the character or the saga overall, but I can’t really imagine Chapter 19 of 25 would be the place for anyone to start, other than some kind of random coincidence.

How the Film Speaks to 1968:

I’ve watched Samaritan Zatoichi twice now, and really there doesn’t seem to be anything going on in the film thematically or plot-wise that brings the characteristics of the latter half of the 1960s to mind. The most indicative highlight of this movie’s temporal origins is the opening credit sequence, where the cast and crew names are flashed across the screen against neon-bright fields of fluorescent color, with an effect that dazzles the eye for a few moments before giving way to the usual widescreen ratio we expect from films of this vintage. There’s no apparent exploitation of generation gap tensions (other than a comical run-in between Ichi and a gang of young boys trying to trap sparrows in the opening pre-credit sequence), and the sex-and-gore exploitation factor even seems to be dialed back a bit from other Zatoichi flicks of this time – a couple fingers get lopped off, and there’s a wrist stabbed with a hairpin, but that’s all fairly tame. Even the scenes set in a brothel could have been revved up with the sexiness quite a but more as far than what Misumi decided to go with, indicating that the producers probably had more of a general audience in mind when the film was released in the waning days of 1968. Samaritan Zatoichi does feature one of the grittier one-on-one final boss battles though, I’ll give it that.

Thus the film stands somewhat apart from the particular concerns of the era in which it was created, and that timelessness is more of a strength than a liability.

How the Film Speaks to Me Today:

Beyond the simple pleasures of once again watching a familiar and beloved character embark upon another satisfying adventure that covers familiar generic bases, I’m most intrigued about the film’s title. Samaritan Zatoichi of course is an allusion to the biblical story of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:25-37), a parable taught by Jesus that admonishes his hearers to show mercy to strangers when we see they are afflicted, and to be open to the possibility that members of groups we despise and mistrust might be capable of behaving more kindly than others whom we tend to consider worthier of our respect, admiration and social deference. It’s not all that difficult to draw a parallel between Zatoichi, the despised handicapped outsider who rescued a woman seized upon by greedy criminals, and the scorned Samaritan of the parable whose generosity to the robbery victim exceeded what was demonstrated by the priest or the temple worker. But there’s nothing about Ichi’s behavior in this story that makes it especially worthier of the comparison than just about any of the tales told in the earlier chapters. The swordsman/masseuse always shows himself ready to come to the aide of the oppressed and downtrodden, whenever he hits the road and wherever he happens to land. So I’m curious as to where this title originated, especially after learning that the Japanese title Zatôichi kenka-daiko translates as “Zatoichi: Fighting Drums,” which actually does help to explain the eruption of percussion that seems to come out of nowhere in that climactic showdown excerpted above. Maybe a Japanese audience understood the reference more clearly than Western viewers would, but I kind of wish that the title had stuck more closely to the original, perhaps with a little extra effort put into the subtitles or liner notes to provide additional context to help us make sense of that element of the story.

Then again, I guess I have no problem with a reminder about the story of the Good Samaritan. In today’s social and political context, in which expressions of compassion that put our own comfort and sense of security at risk seem to be such a low priority to so many in positions of power and authority, we benefit from whatever encouragements we can find to do just that.

Recommended Reviews and Resources:

- Criterion Box Set

- Top 10 Most Essential Zatoichi Films

- Blood Brothers Reviews

- FreakEngine

- Lard Biscuit Enterprises

- Quiet Bubble

Previously: Monterey Pop