The Trip boasts an unusual combination of dialogue-heavy comedy, of scenic travelogue complete with a focus on high-end food and finally a somber self-reflexive experiment. While these are occasionally at odds with each other, The Trip is hilarious from start-to-finish and ultimately insightful because of the persistent and atypical way it goes about making its point.

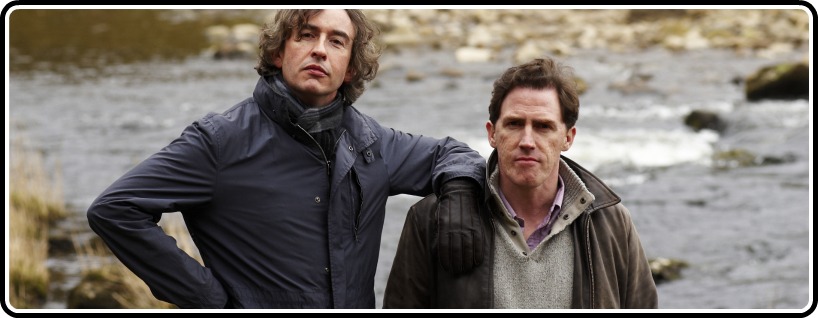

Some necessary background; in 2010, a six episode sitcom aired on BBC Two called ‘The Trip’. It starred Steve Coogan and Rob Brydon as versions of themselves. Steve has recently accepted an offer from The Observer to tour a series of restaurants’ in Northern England and write an article. He mainly did this to spend some quality time with his American girlfriend Mischa (Margo Stilley). Now Steve needs to find someone else to go on the trip because Mischa has moved back to America. He asks his longtime colleague Rob Brydon to go along. Throughout Rob and Steve’s lively conversations, Steve’s unhappiness trickles through as it becomes apparent that he uses the trip and Rob to avoid his own dissatisfaction with life. Director Michael Winterbottom cut down the six episodes into this feature-length film also titled The Trip which lasts slightly under two hours.

The Trip is going to divide people. Those looking for a dynamic that evolves and changes over time are going to be disappointed. A lot of the film is Brydon doing impressions, frequently the same ones. Also, the pair never has it out the way another film would have built up to. The film is enmeshed in repetition, never really going anywhere. These reasons that others will surely jump on as evidence the film does not succeed, are actually reasons the film does succeed.

There is no plot outside of brief diversions into Steve’s life. His ex-wife calls, telling him to call his son and talk to him. His agent calls with a questionable new TV project. Mischa calls with news that she has been assigned to go to Las Vegas for a story on prostitutes. The two are ‘˜on a break’, so neither knows the status of their relationship. Either way, this will not stop Steve from having one-night stands.

Real life comes into play during the scenes that show where Steve’s life and career are in relation to where he wants them to be. The trip itself, which makes up almost the entire film, is meant to be the antithesis of these troubles. It is a completely unconventional way to make a point but it works; the way Steve uses the trip to temporarily and half-heartedly dodge his life is concurrent with the films irreverence. He wants to avoid, and the film allows him this.

Steve’s dynamic with Rob is equally important. Rob is happily married with a child. His life is what Steve’s could never be simply because of his eternal dissatisfaction. Rob sees his career as successful and does not aspire to greatness the way Steve does. Steve quite resents this and is never afraid to insult Rob about his career. Rob never gets angry about it; he clearly expects this behavior from his longtime colleague. Rob, in turn, will occasionally address aspects of Steve’s life, fully knowing that Steve will not give answers that confront much of anything. Steve and Rob have their own established world together (they have known each other for eleven years), further proven when the heavily improvised nature of the film is taken into account.

Their conversations are thoroughly escapist, with a strong air of competition. They throw themselves into moments, songs, melodies and impressions. They are constantly trying to one-up each other, whether by seeing who does the better Michael Caine impression or by testing how many octaves each can sing in. Steve may say to others on the phone that Rob is a ‘˜pain in the ass’, but he clearly gets something out of his hesitant friendship with Rob; the irreverence between the two and their conversations. Each knows what to expect from the other. Steve knows he can vent his frustrations by taking jabs at Rob’s career. He knows their friendship is based on nonsensical conversations. This allows a safety net of irreverence to form for Steve.

These conversations that go nowhere and the constant back-and-forth are all hilarious, resulting in one of the funniest films to come around for a long time. Not to mention the stunning scenic view of Northern England that it gives viewers; it is more than a bonus, existing as an entirely separate reason to seek out the film. It tries too earnestly at first to turn Steve’s life into a pity-party, with awkwardly overt music cues. As the film goes on, these kinks become smoother. A lot could probably be said about Coogan and how this exists as a self-representation. Without having seen Tristam Shandy: A Cock and Bull Story or knowing quite enough about Coogan’s persona to comment extensively, that can be left to other reviewers. Underneath all of the improvised hilarity, The Trip is about understanding Steve and Rob’s friendship, where it comes from, how the film is using their repeatedly competitive conversations and what it all means. Some will see it as a film that goes nowhere. This is precisely the point; it is a story about fame and emptiness, which has been addressed in many recent films, but told in an uproarious, refreshing and unconventional way.