Even though no one could reasonably be faulted for assuming that an unbridgeable chasm of time exists between the filmmakers of today and the Golden Age of Japanese cinema, at least one active link to that era still lives and breathes among us. Japanese auteur Kaneto Shindo, best known in the West for classic 1960s fare like Onibaba, Kuroneko and The Naked Island, is at age 99 probably the oldest director whose name is found among creators of titles that qualify as “recent releases.” His latest and reputedly last film, Postcard, which debuted in Japan in 2010, is now landing in the USA on the festival circuit, played at the Portland International Film Festival on Saturday, February 18.

Shindo will turn 100 in April and his longevity, as rare as it is for anyone to reach the century mark on this planet, is made even more remarkable as one considers the incredible odds that were stacked against him as an able bodied man in the 1940s as Japan hurtled toward its eventual defeat and devastation in World War II. Drafted into a company of 100 men whose lottery-designated assignments sent the vast majority of them to certain doom, Shindo was one of only six men in that group who survived the war years. That burden of cruel injustice for the men who died, and their grieving loved one, and the random draw of a number that kept him out of harm’s way, weighed upon Shindo for decades, and his experiences in the immediate aftermath of that war went on to inform what looks to be the capstone of a long and most impressive artistic legacy that began as an assistant to Kenji Mizoguchi and others as far back as the late 1930s.

Postcard derives its title from an object that linked a man and a woman who would otherwise have remained strangers throughout their lives. On the night before a company of 100 military custodial workers are farmed out to various wartime tasks, one of the men, Sadazo, shares with his bunkmate Keita a note sent to him by his wife Tomoko. On it, she’s written a poetic sentiment expressing how much she misses her husband. Sadazo, knowing that he’s been assigned to fight on the frontlines, understands that he’s unlikely to see his wife again, so he gives the postcard to Keita, who’s drawn an easier assignment, to return the card to Tomoko, should he survive the war, so that his soon-to-be widow will at least know that her message got through to him before he died. Keita takes the card, and the assignment that comes with it, almost as an afterthought, preoccupied with the task immediately at hand.

From there the narrative shifts focus over to Tomoko herself, who lives in primitive conditions with her husband’s frail and aging parents on an isolated patch of land from which they eke their meager subsistence. Their lot is hard and ultimately tragic, but not especially more than so many other Japanese citizens of that time, whose lives and fortunes were devastated by the war and its cataclysmic outcomes. Rather than serve as an especially appalling example of the deprivations that ordinary people had to endure after the war, Tomoko’s suffering is most crushing in the realization of just how common it must have been for so many women like her in those years.

And even though Keita does indeed survive after the war’s conclusion, his fate is no more comforting and in some ways, what he encounters upon his return home is enough to make him wish he had perished along with most of the rest of his companions. A fisherman by trade, he finds himself on the verge of selling off all his belongings and fleeing Japan forever, until he rediscovers the postcard and remembers that one last commitment he has to fulfill to his late friend Sadazo before he begins his new life in Brazil.

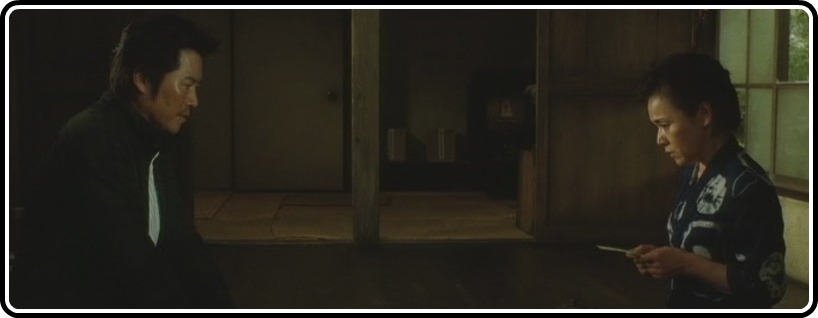

Tracing the address on the card, Keita arrives at Tomoko’s farmstead, finding a niche for himself as he helps her find purpose and resilience in the midst of nearly immobilizing sorrow and depression. A relationship develops between them that’s too scarred by grief to fit the conventional descriptions of a romance. Tomoko and Keita, like the characters in Onibaba and Kuroneko, are both haunted, though their ghosts and demons are of a decidedly non-supernatural origin.

Though Postcard‘s story and characters would be quite powerful had they been crafted by a younger director chronicling the ordeal faced by past generations, they’re made all the more poignant when viewed with the knowledge that this film is essentially a final testament of one who lived out this narrative in real time. Kaneto Shindo, in frail health and with failing eyesight even before production began, certainly had a lot of assistance in putting his experiences on the screen, but his involvement and elegantly straightforward, unsentimental directorial style gives Postcard an indisputable ring of truth.

There are numerous echoes in various scenes of departed grand old masters like Mizoguchi, Ozu and others whose artistic visions were tempered by the flames of war, but Shindo’s own The Naked Island is referenced on several occasions, in routine gestures like a couple bearing heavy yokes of barreled water and the grinding labor that goes into raising a crop from hard, unyielding soil, as well as its larger theme of stoic persistence in the struggle to survive despite the indifference of the natural and social world around them. Whether or not Shindo consciously intended to make Postcard as a kind of bookend to The Naked Island, which basically launched his international career after nearly 25 years in Japan’s film industry, I found the symmetry between the films quite moving and recommend that they be viewed in close proximity if at all possible. The Naked Island is currently available on Criterion’s Hulu Plus channel. The question remains open as to Postcard‘s viability as a candidate for the Criterion Collection; I think we’ll have to see who picks it up for distribution and what kind of an impact it makes as the film reaches a wider audience before it can be answered. Wherever Postcard winds up in the annals of cinema, I doubt that a more fitting valedictory for Shindo could have been delivered on film.