‘It would be stupid for us to ruin our lives for an ideal.‘

If ever a film was made for an International Film Festival, it’s Certified Copy. A French-funded film directed by an Iranian director, set in Italy, and featuring a script that alternates between French, Italian, and English, it practically needs its own map.

The latest shell game from Abbas Kiarostami is, like many of the director’s films, difficult to describe without being reductionist. In a sense, it’s one long, roving conversation–a little like Malle’s My Dinner with Andre remade as a more grown-up version of Linklater’s Before Sunrise. British opera singer William Shimell plays James Miller, author of a book about the value of art reproduction as an art unto itself. It’s called Certified Copy, and it does more than lend its title to the film: its major themes are also the themes of Kiarostami’s script. Is there more value in something that is genuine than there is in something fake? Is authenticity important, or is the perception of something’s value what really matters? James, it would seem, would say yes. But then, he also wonders aloud whether he authentically believes in what he is saying or he wrote a book in order to convince himself of his own ideas. According to him, simplicity is best. Like what you like for your own sake.

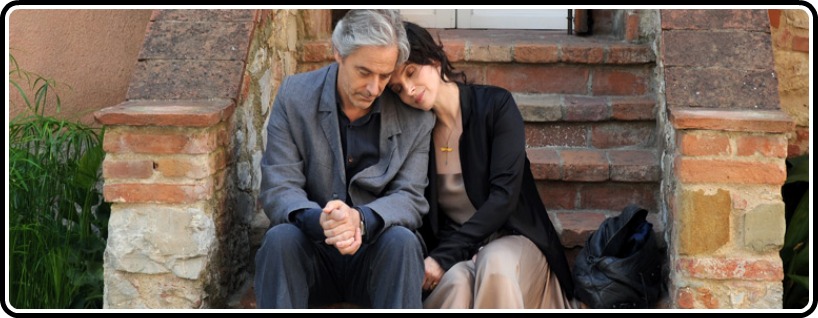

French actress Juliette Binoche plays Elle, a single mother, or so we assume, who is a fan of James’ book and also annoyed by it. She likes what it explores, but doesn’t agree with all the conclusions. When James visits the Tuscan town where she lives with her son, she takes the writer out for a Sunday drive. They end up stopping in a village where couples go to get married because it is supposed to be good luck. Even this becomes fodder for debate. Shouldn’t they be marrying for love rather than kidding themselves that there is some other force helping them along?

Every stop on their journey through this town adds more to the discussion, be it a café, museum, or public square. The back and forth becomes more heated, particularly as past connections are revealed between them. As some might say, ‘shit gets real.’ Except we’re never sure if it does. When an old woman running a coffee shop mistakes James for Elle’s husband, she doesn’t correct her, and suddenly they share this seemingly invented life. James goes along with it, and Kiarostami quickly sews the seeds of confusion. Just what is between these two?

Kiarostami has dealt with themes of adopted identity before, most notably in his film Close-Up, a reenactment of a true story about a man passing himself off as a famous Iranian film director and the family that agrees to be in his ‘movie.’ Kiarostami is a director who is interested in the relationship between truth and fiction, of the illusion of cinema and how the audience accepts it. His 1997 film A Taste of Cherry famously removed the veil in its final shots, showing the film crew standing nearby. His last movie, Shirin, was composed entirely of images of different women (including Juliette Binoche) watching the same movie, the film’s narrative consisting of their reactions to the other narrative being shown offscreen. Given that the women were looking straight ahead, it made the audience the unseen movie. We watched them watching us. Certified Copy also brings to mind vague echoes of Kim Ki-Duk’s Real Fiction, though the Korean filmmaker’s voyeuristic verité and use of doppelgangers is far more abstract and psychologically trying.

Certified Copy doesn’t resort to such self-reflexive tricks; instead, Kiarostami offers multiple metaphors for his central question that keeps the audience on its guard. There is the painting in the museum that, for two centuries, was believed to be from Rome, but that had recently been discovered as being a forgery from Naples. It now hangs as a multi-layered object: what it is and what it is a copy of. But can’t it exist on its own? It’s not like the original painting wasn’t a copy of real life. Later, James and Elle visit a fountain with a statue that is meant to depict true love. Next to it, the strained relationship between the flesh and blood couple seems diminished. Which is more of an approximation?

The director playfully toys with the visuals throughout the film. Scenes often appear on two planes, with one actor present in the frame and another visible from outside the shot, seen as a reflection in a mirror or glass. Kiarostami is creating copies of his own performers, calling attention to the artifice through the construction of his image. The day out for James and Elle is a relationship occurring at warp speed. It escalates from nervous first impressions, through getting to know each other and straight into commitment, and then into exasperated familiarity. Amusingly, throughout their walk, the other couples the pair meet keep getting older and older, newlyweds to feeble senior citizens.

Juliette Binoche is a treasure. I think she’s incapable of a bad performance. She is the gravitational pull that dictates which way the tide flows in Certified Copy. Hers is a fully inhabited performance, complex in its emotional range. There are moments of tremendous heartbreak, but she also expresses hope and joy and frustration with equal strength. Her face is a sophisticated tool, capable of conveying any thought or emotion. The less-experienced Shimell can’t quite keep up. There are times when his acting appears mannered and put-on, usually when he is peering directly into the camera. It doesn’t really hurt the film, but you can’t help but wonder how much better Certified Copy could have been if Binoche were sparring with a champion of equal strength.

In addition to the scenes where we see one of the actors reflected in a random surface, we also get two scenes, one for each character, where James and Elle regard themselves in a mirror. (Like Shirin, what they are looking at, arguably, is us.) It’s in these moments that both seem to be making a decision of how much they are willing to reject the invention. If a fake life is as legitimate as a real one, then there is no reason to go along with it. Or, depending on how you choose to see it, they are maybe discarding the illusions and excuses that have kept them apart. The veracity of the experience is in the purview of the individual viewer, which could be Abbas Kiarostami’s most appropriate object lesson yet: how much you choose to accept his fiction only reinforces Certified Copy‘s driving conceit.

Certified Copy plays the Portland International Film Festival on 2/12 and 2/14.

1 comment