I could belabor the point, but we all know that one thing is true as we come to the close of 2020: this year can go absolutely straight to hell.

However, I’m not going to wax philosophic about how movies have forever changed and how distribution models are never going to be the same. That’s what the last 10 or so months have been for. Instead, while the year may very well be the “worst” in modern history (honestly, however you quantify year quality, this has really sucked), it also gave us one of the better film years in recent memory. With film festivals going digital and major film releases arriving in homes almost instantly upon release, this has been a crowded and fruitful year for an ever evolving medium.

So let’s get on with it. These are the 25 (or so) best films of 2020, as ranked by yours truly:

25-11: The Runners-Up

25. On The Rocks

24. Work (or To Whom Does The World Belong)

23. She Dies Tomorrow

22. Her Socialist Smile

21. True History Of The Kelly Gang

20. First Cow

19. Expedition Content

18. Time

17. Undine

16. City Hall

15. Da 5 Bloods/American Utopia

14. Martin Eden

13. The Last City

12. Days

11. Point And Line To Plane

The Top 10

10. Beginning

Starting off this year’s final top 10 is one of the year’s most exciting debut directorial efforts. The first feature film from director Dea Kulumbegashvili, Beginning is a full-throated announcement, on a global stage, of a new and deeply important voice in world cinema. The film introduces viewers to Yana, the wife of a leader in a Jehovahs Witness community in Georgia. From its incredible opening shot, however, the film subverts any and all expectations. Opening on a shot of a congregation meeting within a house of worship, the sequence culminates with an act of heinous violence that permanently changes ones expectations, moving expectations from that of a relatively simple story of faith found in a small community to that of an almost breathless escape of its lead from a society seemingly bent on destroying her.

Shot in an almost assaultive 1:33 aspect ratio, Beginning is a beguiling work of craft and storytelling. There are striking images here that are deceptively simple, yet hint at a quiet interiority that glances more towards experimental video art more than anything classically narrative. This, in turn, pairs brilliantly with the deeply naturalistic lead performance of Ia Sukhitashvili. In this beautiful stillness a life of exasperated resignation grows, and so does a brooding, breathtaking rumination on oppression where what’s just out of one’s line of sight is even more dangerous than the world they see clearly.

9. The Giverny Document (Single Channel)

Next up is a medium-length film entitled The Giverny Document (Single Channel). The film’s directed by Ja’Tovia Gary and through a blend of various techniques ranging from woman-on-the-street interviews to animation it ruminates on the perceived safety of Black women in America. Shot in both Harlem and Monet’s gardens in Giverny, France, the film is a brisk 41 minutes and while that may not seem like it will pack much of a punch, it in actuality stands as one of the more intellectually dense films in this year’s lineup.

Gary’s film is at points beautiful and experimental, at others hopeless and terrifying. “Do you feel safe” is the film’s primary question, and over these 41 minutes Gary discovers answers that are sometimes haunting, other times empowering, and many absolutely soul crushing. Yet never are they not captivating, making this engrossing art film one of 2020’s biggest discoveries.

8. The Woman Who Ran

At just 77 minutes, director Hong Sang-soo’s latest is a briskly told story, a naturalistic rumination on human connection in an increasingly distanced world. Again playing on his clear affinity for the films of Eric Rohmer, Hong once again teams with his on and off-screen muse Kim Minhee, who stars as Gamhee, a young woman who is in the midst of a trip sans her husband for the first time in quite a while. More or less a collection of interactions between Gamhee and three of her long-time friends, The Woman Who Ran is a beautifully tender picture, one of Hong’s breezier works and also one of his most emotionally textured.

In comparison to much of Hong’s recent work, this film is almost farcical, finding its director at his most humanist. Jettisoning much of the metaphysical qualities of his recent work and in its place embracing a heartfelt naturalism that itself is manifested in Minhee’s incredible performance. A film very much about the anxieties of modern life, The Woman Who Ran is a potent and deeply personal film, a film that doesn’t cut out the more reflexive parts of Hong’s storytelling, instead distilling them down into a brisk and tender story of human connections.

7. The Inheritance

Coming in at lucky number seven we have one of the great discoveries from this year’s New York Film Festival. From director Ephraim Asili comes The Inheritance, a Philadelphia-set drama, which itself blurs the line between fiction and non-fiction while standing as a vehicle for expression of black liberation. Blending together a documentary about the Philadelphia liberationist group MOVE with a fictional work about a collective trying to reach some semblance of political consensus, the film is a gorgeous and evocative work of cinematic revolution.

With clear influences ranging from Tarkovsky to Sam Greenlee’s seminal The Spook Who Sat By The Door, Asili’s film owes its greatest debt to the work of Jean-Luc Godard, whose iconic La Chinoise plays not only as a literal reference (a poster is seen throughout) but its closest stylistic relative as well. The photography here is utterly breathtaking, and each performance is properly textured and modulated. It’s cliche to say a film is of a moment in time but few features spoke more to larger cultural movements seen in 2020 than this expertly made, deeply radical picture.

6. Labyrinth Of Cinema

Next up is one of the most talked about foreign language films of 2020, a final film from a genuine master of world cinema. From the late Nobuhiko Obayashi comes Labyrinth of Cinema, a ground-shattering conclusion to one of Japanese cinema’s great careers. A densely packed three hour magnum opus, Labyrinth tells the story of three men who are transported into a series of Japanese war films being shown at a theater on its last night being open.

Bombastically anti-war, the film is a love letter not only to cinema as the premise would have one imagine, but also a thrilling and audacious meditation on the power of cinema to connect people through space and time. Embracing every trick and gimmick the director has ever used into one eye-popping extravaganza of surrealism, Labyrinth is a thoughtful and thought-provoking acid dream that finds Obayashi distilling all of his interests and passions into a final sonic boom from one of cinema’s great experimenters who saw cinema as a way to connect nations to their history and one generations to one another. A deeply moving and important work from a timeless cinematic genius.

5. To The Ends of The Earth

Coming in right at the middle of this list is the latest from beloved director Kiyoshi Kurosawa. To The Ends of The Earth tells the story of Yoko (Atsuko Maeda), the host of a travel show who, while filming an episode in Uzbekistan, becomes subject to a series of events that challenge her to keep her wits about her while being faced with almost absurd roadblocks. For a filmmaker best known for horror films, this is Kurosawa in a more humanist mode, and is at points one of his most funny films, while also being one of his most overtly moving.

A genre-bending portrait of one woman’s existential isolation where the burst of theatricality and surrealism only compound the film’s power. There’s particularly a musical sequence near the end that marks the film at its most rapturous, pointing towards a beautifully composed drama that finds its filmmaker working in a decidedly humanist key. It’s heartbreaking and, while working through similar themes of alienation and loneliness that mark much of his more genre-affected pictures, this seems to be a shift in a new, earnest direction for the beloved auteur. Minimalist, sure, but while it’s plot may be relatively “thin” the emotions run deep and powerful in this masterful experiment in narrative.

4. Fourteen

The latest film from cult filmmaker Dan Sallitt is up next and, entitled Fourteen, the film tells the story of Mara and Jo, friends since childhood who, now in their twenties (when we first meet them at least), are at a fork in their proverbial roads. Jo, the more extroverted of the two, is a social worker seemingly incapable of maintaining a long term relationship with anyone other than Mara, and even then the connection is full of love, but quite fraught. Mara, a more reserved and cautious being, makes her way as a teacher aide while trying to make it in the world of fiction writing. Not afraid of making new connections herself, Mara begins to create some semblance of a home with a young software engineer who she begins dating shortly after viewers are introduced to her.

Over the next decade or so, Sallitt follows these women as they traverse relationships both new and old, and all the happiness and heartache that come with it. Continuing in the director’s tradition of quiet, thoughtful and thought-provoking character studies, Sallitt’s latest is a beautifully written film that finds its beauty not in large, maudlin moments of melodrama. Instead, the film builds its texture upon brief glimpses into these lives, lived in moments of humanity drawn out into vignettes woven together in a manner where time is as fluid as the relationships we find these women in. Spearheaded by two incredible performances, gorgeous direction and a vaguely experimental storytelling structure, Fourteen is maybe the great American film of 2020.

3. The History Of The Seattle Mariners

Coming in in the bronze position, one of the more controversial additions to this list. Entitled The History of The Seattle Mariners, this nearly four hour epic is currently available on YouTube (as intended), and comes from the mind of one of that platform’s most important and exciting auteurs. Jon Bois stears this ship over it’s relatively mammoth runtime, and for those familiar with his various series over at SBNATION (Pretty Cool and Chart Party being the two most well known) this won’t come as any real surprise. Telling the story of, you guessed it, the history of Seattle’s beloved baseball team, arson and all (just watch, you’ll see).

Despite being little more than music, archival materials and an abundance of analytics charts, Bois and Co. have created one of the great films of 2020, and one of the more moving and powerful works ever to crop up on YouTube. Surely modest in style, it’s not short on emotion or intellect, pairing seemingly dry statistics, dates and names with profoundly rich backstories and engrossing ruminations on analytics, politics, the poetry of sports and the power of art. And that’s just in the first couple “chapters.” To Bois, these numbers and names aren’t just blips in history books. They are the very history itself. There’s always a narrative. Always a story. Truly nothing quite like it in 2020.

2. The Cloud In Her Room

Next up, and standing as the penultimate film on this list, we turn to one of the more buzzed about foreign language films of the year. The debut feature for director Zheng Lu Xinyuan, The Cloud in Her Room follows 22-year-old Muzi (Jin Jing), a woman attempting to make her way through an increasingly isolating Hangzhou. A film very much about the navigating of modern spaces both literal and figurative, Zheng Lu Zinyuan’s film follows Muzi as she returns home to celebrate the new year with her family, only to dig up old proverbial skeletons. Shot in impressive black and white, the film is an icy one, yet one of increasing intimacy and humanism. An occasionally surreal mix of documentary and fiction filmmaking techniques, bringing about comparisons of other modern Chinese filmmakers, who so brilliantly blur the lines between fact and fiction in order to hammer out larger ideas about a dramatic change in their homeland.

Here it’s something as simple as suddenly shifting to a negative version of the scene we are watching, inverting the black and white contrast into almost pure abstraction. And this abstraction is even done in a much more physical manner. Maybe the film’s most startling scene finds our lead simply taking a calming bath, a soothing moment that turns into one of maybe discovery as she moves her hand down to her pubic hair, the camera moving in to watch as each strand bobs up and down in the calming water. It’s a close-up of genuinely gobsmacking proportions, turning something seemingly purely carnal into a deeply moving moment of artistic abstraction.

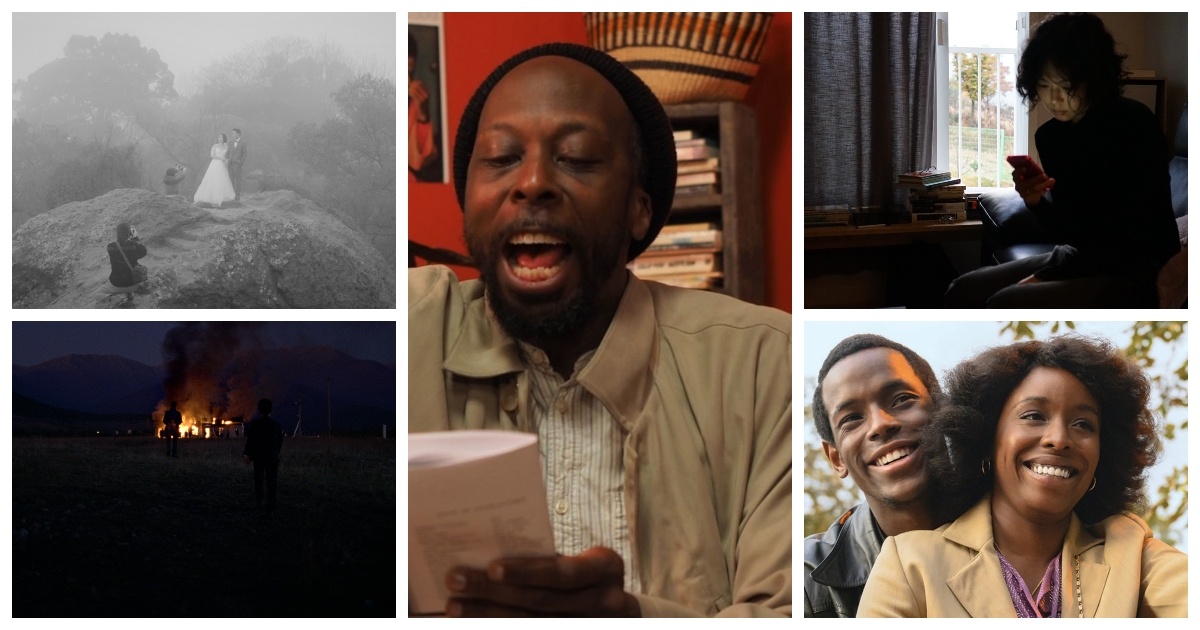

1. Lovers Rock

This year, unlike most, picking the best film was actually not all that difficult. Could have done (and frankly did) it after seeing the film the very first time, let alone the second or third. Steve McQueen’s Small Axe series, totaling five films, stands as one of the great series in all of modern cinema, and one film stands above them all. Entitled Lovers Rock, McQueen’s roughly hour-long, all-in-one-night masterpiece tells the story of two people who, over one evening at a house party, begin a romance. The first word that comes to mind when trying to internalize Lovers Rock is texture. His most mature and nuanced film yet, McQueen’s camera is intimate and sometimes claustrophobic, without ever being distracting or out of tune with the film’s larger mood and atmosphere.

Culminating in a set piece set against Janet Kay’s “Silly Games,” Lovers Rock is for much of its runtime a potent picture about some semblance of puppy love, but it’s also a deeply political picture as well. Near the film’s conclusion this spiritual bubble is more or less burst, sending the film into relative chaos, itself culminating in a sequence set to a track entitled “Kunta Kinte Dub” that feels less like a continuation of the party itself than a forceful response to the abuse and racism viewers witness just moments prior. It’s truly the best film of 2020 and one of the great achievements in modern cinema.