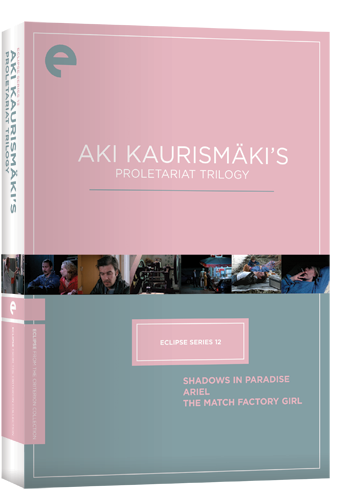

Though he hasn’t quite risen to “blaring headlines” level, Aki Kaurismäki’s name has been generating something louder than a low rumble in terms of buzz over the past few weeks. As our intrepid news reporter Josh Brunsting noted recently, the Finnish auteur’s newest film Le Havre, fresh off its debut at Cannes, was picked up by Janus Films for US distribution a short while ago. And Criterion announced last month that Kaurismäki’s Leningrad Cowboys films are slated for an October release as the latest addition to the Eclipse Series – a development that caught me and many others by surprise, but one of the most enjoyable sort. Given all that Kaursimäki zeitgeist, it seems only natural for me to wind up my coverage of Eclipse Series 12: Aki Kaurismäki’s Proletariat Trilogy with my third review from the set, The Match Factory Girl. (Here are the links to the first two, Shadows in Paradise and Ariel, if you want to catch up on those.)

As I’ve already explained in this column last week and on Twitter, my past week’s movie-watching has, for the most part, been dedicated to watching the films of Mikio Naruse, as I’m gearing up to watch When a Woman Ascends the Stairs for my Criterion Reflections blog. Sensing that I would benefit from a slight respite from watching a steady stream of Naruse’s black-and-white, female-centric Japanese melodramas, and with the current uptick of interest in Kaurismäki, I thought it would make a nice change of pace to give my attention to something more modern, acerbic, ironic and comedic, at least as far as the Eclipse Series is concerned.

But as it turns out, The Match Factory Girl actually fits in quite consistently with Naruse’s themes of culturally-repressed women enduring hard times and seeking some kind of relief from the casual indifference or outright cruelty heaped upon them by callous, inconsiderate men. Both directors skillfully draw our attention to the profound nonverbal messages their characters send to each other through poignant facial expressions and pregnant stretches of silence that draw out, especially in Kaurismäki’s notoriously reticent Finnish milieu, to painful and awkward conclusions. And like several of the films in Silent Naruse, The Match Factory Girl only runs a little past one hour in length. Sure, a lot of the surface differences remain (color, language, widescreen format, the use of humor, etc.) but at their heart, both Kaurismäki and Naruse succeed in giving privileged guys like myself a hefty serving of food for thought on how we treat (or simply view) the women around us in our everyday interactions and assumptions.

I entered into viewing The Match Factory Girl expecting more of the deadpan sardonic humor that infused the previous two installments of the Proletariat Trilogy. But a quick scan of the Eclipse liner notes, and simply viewing the film itself, quickly dispelled me of that notion. An early scene of a family sullenly watching the news in implacable, indifferent silence as coverage of the Tianmen Square massacre and an exploding gas pipeline that kills hundreds of train passengers in Russia sets a “life sucks, grimly endure it” tone that never really lets up.

This is a fundamentally darker film than either of its predecessors in the trilogy, not that those films were all rainbows, butterflies and fluffy bunnies. The three stories share a common theme of financially struggling, working-class protagonists who find themselves driven to desperate measures after being backed into a corner through adverse circumstances – a characteristic quite similar to the tropes that Naruse works so efficiently and creatively in his own ouevre. Hell, there’s even a deux ex machina auto-striking-a-pedestrian incident in The Match Factory Girl – was Kaursimäki invoking an explicit tribute to Naruse in that scene? I can only speculate here, and it seems like quite a stretch in some ways, but the coincidence is uncanny from where I sit.

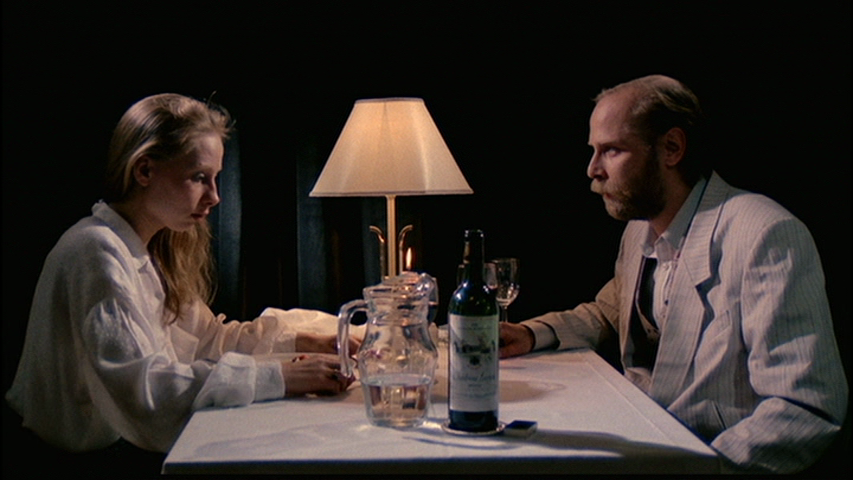

In keeping with its abbreviated length, the film’s story is pretty simple and straightforward, capturing a brief but crucial snippet in the life of Iris, a young woman consigned to blue-collar drudgery in her job at, yes, a match factory, where she toils away the hours on a variety of menial tasks, mainly monitoring small packages of matches as they roll through various stations on the production line. Most of her time is spent in silent isolation, and much of the film is strictly visual, with a bare minimum of dialog. More footage is dedicated to characters staring at each other, or silently off into space, than in active verbal engagement.

Some of the film’s most forlorn sentiments aren’t even spoken, but rather sung, by the music hall crooner used by Kaurismäki to drive home the bleak plight faced not only by Iris but also the anonymous crowd on whose fringes she remains. But when spoken lines are delivered, they’re short and devastatingly blunt. Iris’s world, whether it involves spending time with her family, her co-workers or a cluster of strangers at a bar, is a cold, lonesome and alienated place. The feeling is as if everyone has more or less run out of things to say, with most conversation merely a means of reinforcing social limitations that are otherwise observed mainly through a rigid and unrelenting code of unquestioning but angst- provoking silence.

In her limping efforts to rebel against the oppressively stultifying order of things, Iris is a surrogate for everyone who has a notion that life could be better, could be characterized more by love and happiness rather than exploitation and cruelty if we simply redirected our goals a bit – but sadly lacks the means to express or persuade others of this noble possibility. What Iris wants isn’t really all that complicated, hardly outside the power of a willing human heart to provide, but still proves ever so elusive.

As we follow Iris through her lumpen routines – a drab shift at the factory, apathetic brush-offs from supposed friends, a sullen meal with the parents she still relies on for room and board, a futile night at a local music hall where she fails to attract the attention of potential male companions – we recognize the toll taken on human lives that are first and foremost viewed as a commodity to serve the interests of the social and economic system, and only secondarily as valued entities for their own sake. Iris shows some initiative, going down the consumerist route to buy herself some attractive clothes (though she pays an additional price for it, in further diminished self-esteem, when her parents see how frivolously she spent her money) and setting herself up for exploitation by an unscrupulous, self-centered man who zeroes in on her desperation and takes full advantage.

The setbacks and rejections that Iris has to deal with aren’t especially surprising in themselves, but they’re delivered with breathtaking cruelty by people who feel no compunction about dismissing her outright as a person, even though they ought to know better. As a commentator, I can make the case that life improves for everyone involved when compassion is exercised and people treat each other with respect. However, Kaurismäki wisely chooses not to soften the impact of his film with sentimental expressions or small touches that provide moments of emotional relief for the sake of a broader popular audience. As the liner notes point out, there are touches of humor, grim though it may be, to catch and seize upon, if one is looking for some modest entertainment. Overall though, The Match Factory Girl is a sobering parable of what can happen, whether externally in the real world, or internally to an individual psyche (both equally tragic, in my estimation) when a person wakes up to the fact that the cheap imitations of pleasure, meaning and satisfaction that have been promoted over the course of a lifetime are exposed for the hollow and cynical manipulations they’ve been all along.

The clip shown above is a spoiler-free excerpt from the first few minutes of The Match Factory Girl. It serves as a fitting metaphor for what Kaursimäki has to say here, as we see something substantial and integral (in this case, a tree, though it might just as well be a human being) shaved off, chopped up, shredded, processed and packaged down to the level of becoming a disposable object, something to be sold, struck, burned, tossed aside and forgotten about, taken for granted in its insignificance and swept up with the rest of the debris without another passing thought.

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)

great film, I hope that more of Kaursimaki’s work (and that of his brother) is released in the States.

It`s a great movie. I love foreign movies and especially Kaursimaki’s work.

Eric, I’ve seen Mika Kaurismaki’s credit as producer and figured he was a relative, but didn’t know until I read your comment that he makes films himself. Any particular titles that you would suggest to see Mika’s best? Why do you think Aki gets so much more attention from Criterion, at least at this point in time?

I think that Mika’s work is just not been as embraced because he’s mostly unknown in the states. I have only seen one of his films, Zombie and the Ghost Train, which I saw a decade ago on VHS from a small video store in Moscow Idaho and have never seen another copy of. A Swedish friend told me about the film and I checked it out. I wish that I remembered more about it.

I think that Aki was also embraced by other film makers because of Leningrad Cowboys Go America and his segment of Night on Earth having appeal outside of Finland.