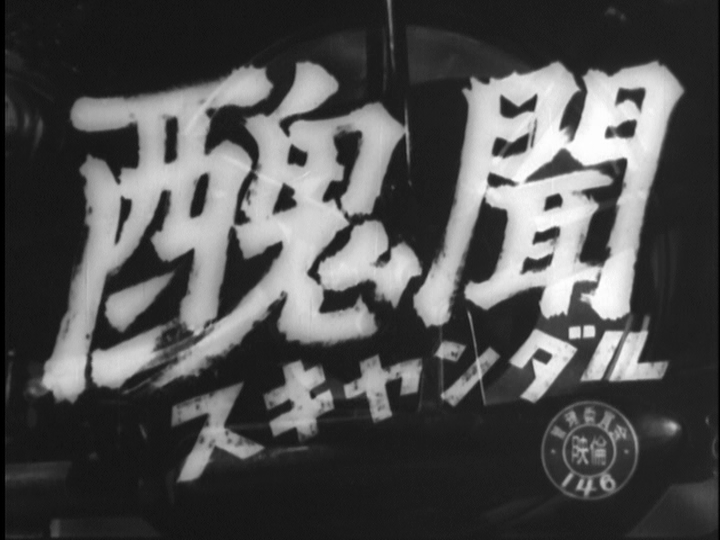

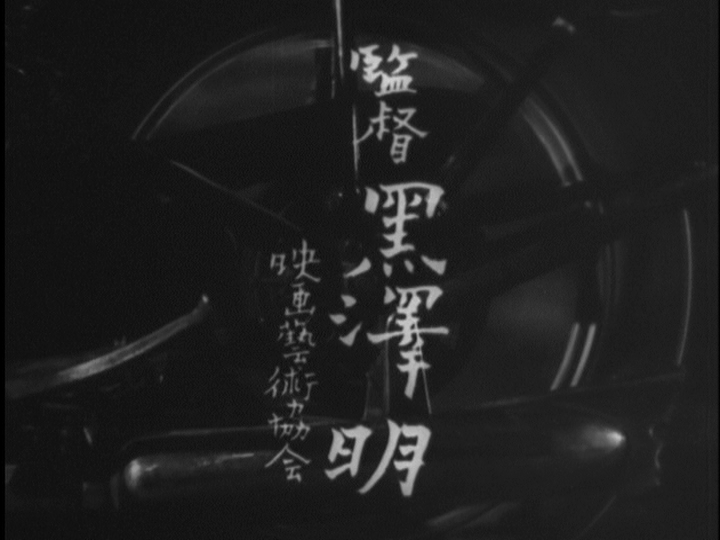

Another one of the great films of Akira Kurosawa is about to receive its well-deserved upgrade to the Blu-ray format tomorrow, as Criterion is re-releasing his 1963 masterpiece High and Low, based on the same package and supplements it received in its DVD reboot a couple years ago. To mark the occasion here in this column, I thought it made sense to acquaint myself with Scandal, an earlier example (from 1950) of Kurosawa’s career-spanning analysis and critique of modern Japanese society, found in Eclipse Series 7: Postwar Kurosawa.

Even though he’s typically less celebrated for his contemporary dramas, compared to his awe-inspiring samurai and historical epics, everyone who’s come to admire Kurosawa for his ability to stage compelling spectacles set in the distant past owes themselves the opportunity to see what he achieved when he focused his attention on the contemporary context.

Scandal was the last film Kurosawa made before he completed Rashomon later that same year and first established himself as a filmmaker of global significance. Putting the two films side by side isn’t really a fair competition – Scandal can be seen as the last feature of his early formative period, while Rashomon initiated a run of superb productions that went on to wield massive influence on a generation of directors and other creative types.

Though Scandal is rightly regarded as belonging on the secondary tier of Kurosawa’s filmography, that shelf still ranks pretty high up there, and the numerous pleasures awaiting our discovery make watching it time well spent for those who appreciate not only Kurosawa’s distinctive touch but also the actors who collaborated so effectively with him on so many films: luminaries like Toshiro Mifune and Takashi Shimura (who both appear in High and Low, though Mifune’s role there is much bigger) or even memorable bit actors like Bokuzen Hidori, the sad-faced wretch who always makes such a vivid impression when he shows up in minor parts, usually as a drunkard. (You can see him in the video clip further down the page.)

As the title suggests, Scandal is a bit of a potboiler, though it’s more of a slow simmer than a red-hot cauldron splashing over the brim, as far as salaciousness is concerned. The story involves a painter, Ichiro Aoe (Mifune) and a popular singer, Miyako Saigo, who meet by chance on a mountain road one afternoon. She’s just missed the bus to her hotel and when he learns that she’s staying at the same place he’s headed, he offers her a ride on his motorcycle.

They proceed to get acquainted on the most casual and innocent of terms, but as many a celebrity has learned over the years, pure intentions aren’t sufficient to stand in the way of a juicy and potentially profitable piece of gossip that winds up in the hands of those who know how to exploit it in popular media.

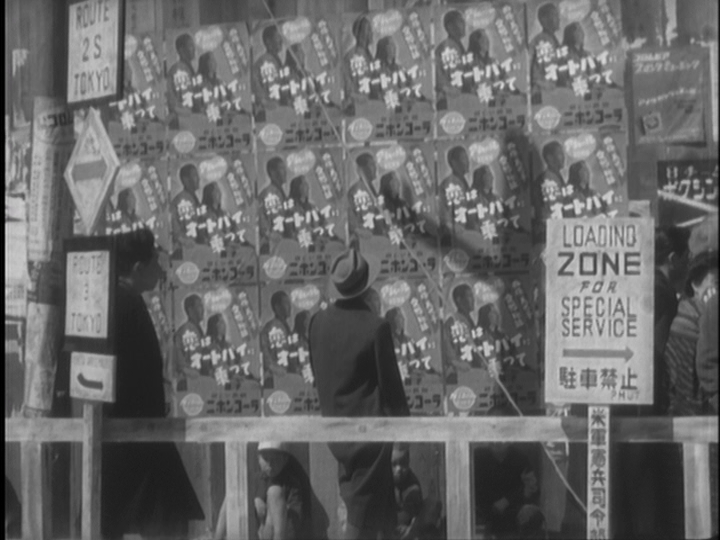

Kurosawa and Mifune do a great job establishing Ichiro’s guiding principles, his recklessness and passion for life captured in his reliance on a loud rumbling motorcycle as his primary means of transportation. He even uses it later in the picture to deliver a Christmas tree to an impoverished household. As he tells Miyako by way of a conversation starter, he likes that “attitude of not giving a damn” that comes with being a biker, since “it feels good being rude.” The muffled rumble of his engine becomes a signifier of Ichiro’s off-screen arrival, presence and departure in later scenes, just a small indication of Kurosawa’s growing virtuosity as a filmmaker. His use of montage, snappy dialog and adroit editing flourishes also pack a lot of punch, showing a sly subversive wit as Japanese cinema continued to emerge out from under the control of American censors in the final phase of the US military occupation.

Miyako is a much more reserved, inhibited personality who finds Ichiro an intriguing diversion, and surprisingly considerate company, given her apparent fear of harassment and off-stage attention that comes from being a popular entertainer. Miyako just loves to sing, and does it very well – she’s not looking to be a national sweetheart or fodder for the gossip magazines, but it’s a fate she simply can’t avoid.

The few minutes they share on a balcony after refreshing themselves from the trip to the mountains gives a pair of spurned paparazzi the opportunity to snap a quick photo of them together. They resent Ichiro for not giving them an interview or an opening to meet with Miyako themselves, and their grudge (not to mention the chance of turning a quick buck) leads them to fabricate from out of that slim piece of evidence the insinuation – published broadly and advertised sensationally – that something much more illicit (by 1950 standards, anyway) went on behind the scenes.

Given Kurosawa’s obvious disgust and contempt for what seems to us like a comparatively mild culture of celebrity gossip and exploitation, one shudders to think what he would make of the lurid commercialization of people’s intimate affairs that we take for granted today. Even though a 21st century pop star, or for that matter a member of their entourage, would hardly be bothered by the particular allegations leveled at Ichiro and Miyako by the publishers of Amour magazine, it’s still easy to relate to the anger shown by Ichiro as he sees others profiting at his expense by reporting things that never happened.

It’s also fun to see a few vintage displays of Japanese pop culture circa 1950 as Western influences established an ever-growing foothold that has long since been reciprocated by the role of J-Pop iconography in US and European style over subsequent decades.

Kurosawa clearly has fun presenting the crooked, amoral editor Asai as a man driven by empty-handed swagger and blatant vanity, eager to accept the applause of his lackeys when he doles out token cash bonuses but a cowering sniveler when a real man like Ichiro shows up to find out what’s going on, and who’s behind these attacks on his good name and character.

Losing his cool for a moment, Ichiro gives Asai a hard shove, tossing another layer of outrage and entanglement onto the ever-deepening Scandal. Dueling press conferences only serve to bury the truth and further titillate the public, encouraging them to choose sides over who’s really telling it like it is and lending the benefit of plausibility to baseless falsehoods.

As anyone who’s ever been embroiled in a dispute that draws media attention can attest, even the effort to explain your side of the story always seems to complicate things even further, especially when the adversary proves to be so skilled at twisting the truth and spinning every pushback to their own advantage.

Just when we’re sizing up Scandal to consist of a battle of nerves and wits between Ichiro and Asai (played by Shinichi Himori, one of the blind men in Shimizu’s The Masseurs and a Woman), with a side helping of romance between Ichiro and Miyako, Kurosawa throws another twist at us, introducing an eccentric attorney, Hiruta, into the mix.

Hiruta’s unsolicited late night visit is prompted by his empathy for Ichiro’s plight and his willingness to represent him in a lawsuit that the aggrieved painter decides to pursue against Asai and Amour magazine. Played by the great Takashi Shimura, Hiruta’s apparent supporting role in the narrative goes on to expand and eventually dominate the film’s second half.

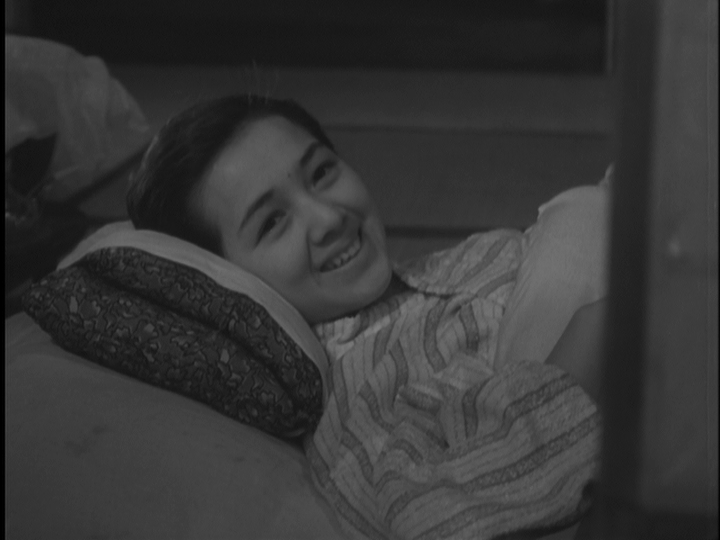

Against Ichiro’s righteous moral clarity and Asai’s unscrupulous cynicism, Hiruta comes across as murkily compromised. His motives for wanting to assist Ichiro are sincere, but also financially driven. His daughter Masako is ill with tuberculosis, requiring expensive medical treatment that he can barely afford, and he also has a bit of a gambling habit, spending his days at the race track when he could be rustling up more legal business.

On top of all that, he has a prior relationship with the crooked editor, who’s eager to ply Hiruta with desperately needed cash in order to leverage some secret influence on the lawsuit’s eventual outcome.

The presence of tuberculosis and even a rancid bog in the midst of a poor urban neighborhood quickly bring Kurosawa’s earlier film Drunken Angel to mind. In Scandal, the sick little girl raises the pathos to the hilt as she utters piercing words of oracular power during her moments on screen.

Presumably her frail condition and innocent spirit give her some kind of privileged insight into the darkness that lurks in the hearts of men, particularly her father, whom she loves but who she also knows is a troubled and unreliable soul.

If Scandal has a flaw that prevents the film from being embraced as one of Kurosawa’s best, the culprit will be its plaintive reliance on sentimental melodrama. That heartfelt earnestness is, of course, one of the things that people love about Kurosawa’s filmmaking, but in this one, his touch isn’t quite as deft, leaving some viewers likely to feel manipulated as he rolls out one emotional powder-keg after another over the film’s final act. The clip above, while entertaining, also seems a bit shameless in its appeal to nostalgia and the desire for camaraderie most of us share.

Still, it’s a great scene in my book, simultaneously winsome in its undaunted optimism and a back-handed slap at the Americanization of Japan, a phenomenon that Kurosawa didn’t view positively but was in many respects helpless to do much about except call attention to what was happening.

Through the character of Hiruta, Kurosawa is reaching out to his peers in postwar Japan, challenging them to reckon with the moral compromises they made over the course of those difficult years, and reminding them that it’s not too late to make the right decision and seize whatever opportunities for redemption they can find.

Scandal winds up as a courtroom drama, though the tension isn’t based on whether or not the jury will rule in favor or against the accused. The person who’s really on trial is the plaintiff’s counsel, though he’s the only one (besides the viewer) who fully understands it that way. In any case, the look on Hiruta’s face right there is most definitely not what you want to see when it’s time for your lawyer to advocate on your behalf!

Even as Mifune’s performance recedes into the background, allowing Shimura to hold center stage and bring Scandal to a somewhat maudlin but still noble and satisfying conclusion, we see hints of greater things to come. Most notably, the parallels between Hiruta and Kanji Watanabe, the protagonist of Ikiru (also played by Shimura, of course) spring to mind: men who’ve overly invested in their careers, losing their way in life in the process but given one more chance to set things right, even if it comes at a substantial cost.

Nevertheless, in this time when we see the transgressions of Rupert Murdoch’s NewsCorp coming more clearly into the light, and with the sad passing of singer Amy Winehouse, whose struggles with addiction were partially fueled by the sick symbiosis between her fame and the tabloid press that perversely celebrated her pathetic decline, Scandal stands relevantly on it own, a tale that needed to be told then, and still speaks to us today.

1 comment