Last week this column featured a review from the most recent Eclipse Series release, Silent Naruse. Sharp-eyed, or perhaps somewhat obsessive-compulsive, readers may have taken note that I had not yet made any mention in this space of the Eclipse set that preceded Silent Naruse. There’s a simple reason for that: I was waiting for the late 50s/early 60s films included in Eclipse Series 25: Basil Dearden’s London Underground to come up in the meticulous chronological sequence I use in my main blog, Criterion Reflections, where I’ve just recently advanced to the movies of 1959. (And with that disclosure, those same sharp-eyed readers are now wondering just who I am to call anyone else “somewhat obsessive-compulsive.”) Well, since I’ve moved past the double feature of First Man Into Space and Corridors of Blood, that point in the timeline has been reached. This week, I’m buffing up and polishing Sapphire.

First though, a brief word about Basil Dearden and what it is about him that warranted an Eclipse release in the first place. Unlike a number of other directors who have yet to break into the Criterion canon, or who remain under-represented in comparison to their career achievements, I never observed any clamor for Dearden to receive his due, nor was there any hint of major celebration or collective gasps of “FINALLY!” late last year when this set’s release was first announced. Even the enclosed liner notes take a slightly apologetic tone, recognizing that even among British directors of his era, Dearden isn’t referenced or seen as especially influential. The man himself is largely responsible for that, since he took on such a wide variety of genres and fair-to-middling assignments over the course of a 30-year career that no defining auteurist tendencies can be discerned.

A quick spin through the entire set that I took a few weeks ago revealed to me that Dearden had a chameleonic ability to crank out crisp, efficient, direct narratives according to the dictates of whatever story was handed to him. But it’s to his credit that he demonstrated a willingness, at least in the four films included in the London Underground collection, to take on provocative social issues. That progressive social critique, and the vintage period settings of mid-century “pre-Beatles” London, are probably the qualities that won Criterion’s favor and nudged them to release these films on DVD rather than just wait to include them in the Hulu Plus streaming deal that was probably being negotiated around the time that the decision was made.

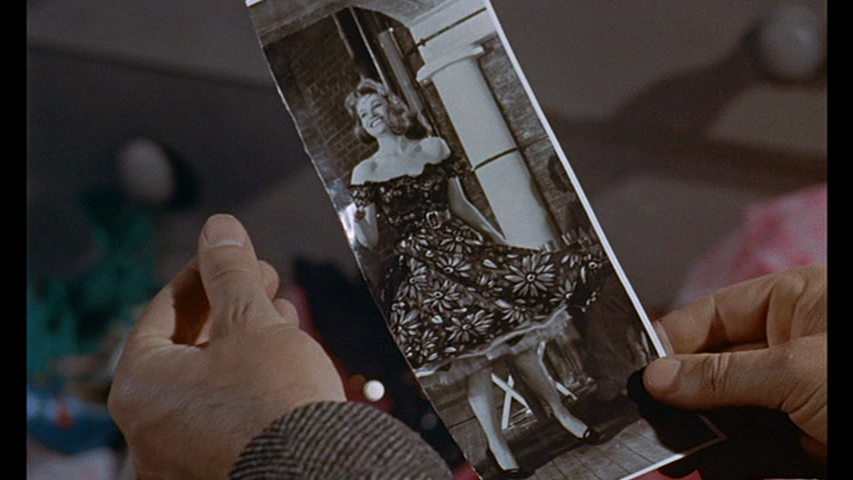

Though Dearden had a few other notable successes to his credit, Sapphire was his biggest award winner, snagging the BAFTA honors for Best British Film in 1960, beating out “angry young man” classic Look Back In Anger, starring Richard Burton, among others. (It lost to Ben-Hur in the overall competition.) Today’s viewers, who may find themselves underwhelmed by the lack of visual flourishes and perfunctory scripting, might find that recognition a bit baffling, but I think the award is a significant indicator of just how challenging and innovative Sapphire was for its time in bringing to the surface some simmering racial tensions and cultural anxieties that had been building over the course of the previous decade or so. As Great Britain’s colonial era came to an end in the years following World War II, dark-skinned immigrants from dominion outposts in the Caribbean and Africa began settling in some of London’s low-rent districts. Though segregation didn’t take on some of the more visibly obnoxious Jim Crow aspects prevalent in the USA, fear and prejudice still clouded the perceptions of many English natives. Sapphire (named after the biracial woman who appears in the film only as a corpse or in a photograph) uses the premise of a fairly standard murder mystery to expose and explore attitudes that were widely held but never expressed quite so publicly in popular entertainment, especially of the notably buttoned-down British variety.

But as admirable as Sapphire‘s breakthrough achievements may be in the context of 1959 England, there’s still a question of how relevant or engaging it is to viewers who don’t have a special curiosity or interest in the sociological dimensions of the film. The truth is, unless you consider yourself something of an Anglophile, I can’t think of too much else to recommend about Sapphire that would compel you to put it on top of your “to watch ASAP” pile. As a mystery-slash-police procedural, there are certainly more flashy and compelling offerings out there, though this one does keep you guessing a bit as to who the killer is, and what motivated that person to stab to death a pretty female student of mixed race who had the nerve to pass herself off as white and enter into a romantic relationship with a young Englishman without first informing him of her “tainted” ethnic heritage. It’s practically taken for granted that the shock of learning that a woman who most everyone thought was white was, in fact, “colored” is enough to drive any number of people into a murderous frenzy. And that, more than the human tragedy of an early and senseless death, is what lingers as the more disturbing subtext of Sapphire.

Similar to the overly self-aware and earnestly stage-managed Crash, which won the Academy Award amidst much controversy back in 2006, Sapphire can’t be faulted so much for its noble intentions as for its inability (for some understandable reasons) to avoid obvious set-ups and embarrassingly simplistic stereotypes in dealing with its chosen topic of racism. Taking a swipe at such a complex set of issues in the course of a two-hour slice of entertainment is a bold move, but almost doomed to fail, at least in the eyes of those who’ve studied and done their own personal work to unpack the latent and blatant racism that infuses so many of our cultural institutions. However, cinema has a valuable role to play in at least bringing the topic up to popular awareness, and in that regard, I do think that a viewing of Sapphire has value, simply as a demonstration of how much internalized racism its various characters display, even those who seem intended as examples of “non-prejudice” (and I’d extend that charge to Dearden and screenwriters Janet Green and Lukas Heller.)

Examples of such unconscious concessions to racist structures and assumptions abound, with numerous scenes involving people of African descent adopting servile voice tones and body language in the presence of white people and the implied endorsement that a failure to disclose the existence of non-white ancestors represents an act of deception. These views were undoubtedly the prevailing status quo at the time, and I’m not blaming Dearden or anyone else for how they chose to tell this story. Rather, my critique is aimed at the corrupting influence of racism itself, an ideology and influence that has proven so difficult to eradicate, in large part because it’s so easily denied and deflected by its past and contemporary defenders.

This video clip offers one of Sapphire’s more aesthetically compelling scenes, as detectives Hazard and Learoyd go looking for clues about the victim’s past in the divey Tulip’s Club. I think it gives a good demonstration of the points I make in the preceding paragraph.

I won’t belabor the argument here, but if anyone wants further clarification or wishes to engage me in debate on any of this, please leave a comment below or contact me elsewhere and we can get into it!

After the scene at Tulip’s, about halfway through the film, Sapphire continues its tour of various London locales, some rather seedy, others more middle-class respectable, dredging up sentiments from voices on all sides of the racial divide that must have stirred up feelings of awkwardness, embarrassment and/or resentment from many in the audience at the time. The Johnny sought by the cops makes a mad dash through late-night alleys, looking for support and shelter from his peers, but they recognize the trouble he’s in and want nothing to do with him, leaving him to be jumped by a gang of Teddy Boys before he’s finally tracked down and apprehended for questioning.

But Johnny’s not the only suspect on Hazard’s list, as he turns his attention toward Sapphire’s boyfriend, David Harris, who had planned to marry her, despite the complications brought about by her recent divulging of blended ethnicity. A bit too shell-shocked and dispassionate to fit the category of angry young man, the portrayal of him and his ornery working-class family indicate hints of the emerging “kitchen sink” sub-genre that was just beginning to make inroads into British cinema at the time.

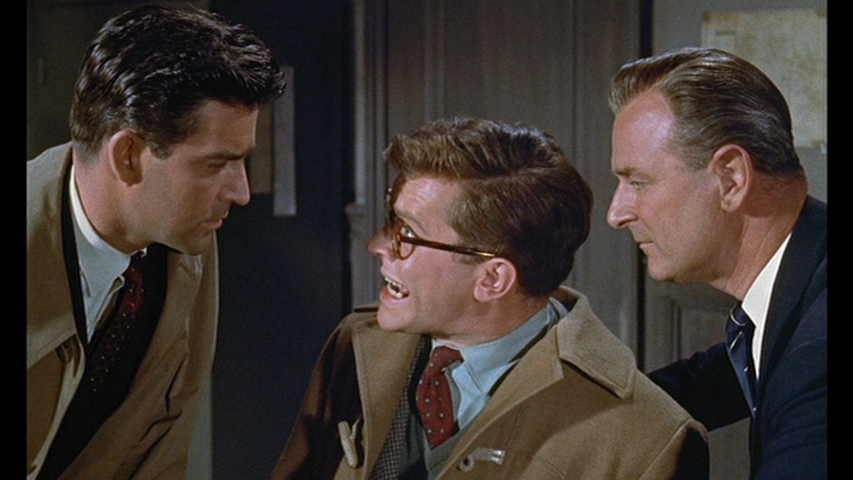

My other main observation, beyond the way that Sapphire deals with race issues, is that as a work of cinematic art, you’re not likely to see much that elicits admiration from the technical perspective. Were it not for the widescreen ratio, what we see on screen could have passed for a TV show with higher than normal production values for that era. Native Londoner Nigel Patrick as Superintendent Hazard makes for a suitable lead figure, handling his role with the kind of poise and polish you’d expect from a well-bred son of actors himself. I recognized him from his supporting role as a rakish young teacher in The Browning Version. His subordinate, Inspector Learoyd (pictured below, walking away in disgust after being mocked by gangster “Horace Big Cigar” and his henchmen), is serviceable, his main assignment consisting of reacting in thinly veiled revulsion when forced to associate with people of color. There’s even one interrogation scene in which I am fairly certain he used the word “nigger” (which actually is used elsewhere in the film) but the dialog was cut just as the “n” escaped his lips.

Any filmmaker who attempts to deliberately raise a sensitive social issue with the intention of stimulating debate and promoting social change runs the risk of creating a cultural artifact with a short shelf life, regardless of whether or not the work produced was effective in achieving its goal. Sapphire is a good example of how ephemeral a cutting edge commentary can turn out to be, and how vulnerable to criticism its creator winds up when people with various takes on the issue want to weigh in to argue their own side of the case. My bottom line on Sapphire is that while it probably wouldn’t make even many Top 500 lists for whatever film fans might be inclined to catalog so many choices, it took that chance and got people to engage, as evidenced by its BAFTA recognition and the fact that I’m thinking and writing about it today. There are more vibrant and intriguing entries to be found in this set, and I’ll get to them eventually, but for the moment, it’s Sapphire‘s time to gleam in this spotlight.

1 comment