As a guy who turned 50 at the end of last month (yes, you read me right – F-I-F-T-Y! I’m having a hard time believing it myself…) this latest string of Criterion movies I’ve been watching sure seems to have a clear message for me: Even if the future looks bleak, Don’t Give Up The Fight. Over on my Criterion Reflections blog, I recently wrote about Le Trou, about a bunch of down-n-out guys doing hard time in prison and risking it all on a long shot bid to tunnel their way to freedom, and Classe tous risques, about a once high rolling gang boss now at the end of his tether, who feels the police moving in and resorts to desperate measures to get him and his family to safety despite the high likelihood of disaster should anything go even slightly wrong. Now my timeline of films from 1960 brings me to The League of Gentlemen, about a group of disgruntled British war veterans who conspire to pull off a massive bank robbery as a quick fix solution to escape the existential corners they’ve all been backed into. All three of these movies focus on themes of men entering into middle age with diminished prospects for the future they once dreamed of, as they harvest the bitter fruit of their past transgressions, left with few options, ready to put on the line what little they have left to lose, just for one last shot at overcoming the odds.

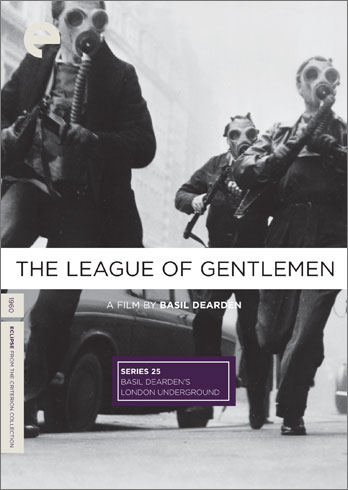

The League of Gentlemen is part of Eclipse Series 25: Basil Dearden’s London Underground, released at the beginning of this year. I’ve already reviewed Sapphire, a 1959 release distinguished as one of the first English films to openly deal with Britain’s growing racial diversity. It made a big impact at the time, and paved the way for Dearden’s follow-up as part of an independent collaborative called Allied Film Makers that rose up to expressly challenge England’s moribund and risk-averse studio system. Though AFM enjoyed early success (with this film being one of the UK’s highest grossing films of 1960,) the partnership only lasted until 1964. You can watch their final film, Seance on a Wet Afternoon, on Criterion’s Hulu Plus channel. (Note: AFM is not affiliated with the Allied Filmmakers production company of more recent years that gave us, among others, The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, A River Runs Through It, James and the Giant Peach, Chicken Run and… Super Mario Bros.)

Though the films collected in this Eclipse box set vary quite a bit in subject matter and tone, the “London Underground” tag fits them well as they each take us on a visit to districts of that great city seldom seen in the movies. That tag could have been literally inspired by how The League of Gentlemen opens, with its striking image of a distinguished looking man in evening formal wear – pinkie ring, cuff links and all – peeping up from beneath a manhole cover in the middle of the road, hoisting himself up after the street-washer passes by and nonchalantly striding down the street as if nothing particularly unusual is going on. It’s never quite explained what he was up to down in that sewer, but that’s beside the point. He’s clearly on the dodge, hiding out from who knows who, but in his defiant persistence, the perfect image of a man who has every reason to despair and yet refuses to internalize his failure. Stiff upper lip, and all that.

Manfully taking his place behind the wheel of his stately Rolls-Royce, he’s a man with a plan and a mission to fulfill. Now all he has to do is round up a suitable company of well-trained and disciplined men like himself – each two steps ahead of “the jig is up” yet still resilient and determined enough to press on, even if the end result is merely to gain nothing more than an additional step beyond their pursuers – and a measure of especially satisfying revenge. (Nice spot for a director’s credit too, by the way.)

As a heist film, The League of Gentlemen takes a leisurely pace in getting its gang together. We first see the chief conspirator, Lieutenant-Colonel Hyde, slicing five-pound notes in half, inserting one section of each into dime-store pulp paperbacks titled The Golden Fleece, and mailing the bundles in envelopes to a select group of men he’s sought out especially for the job. First, there’s Major Race (Sapphire‘s Nigel Patrick), a wartime black market profiteer, born to privilege but now reduced to running an illegal gambling operation and living at the YMCA…

Major Rutland-Smith, a brow-beaten, well-meaning sap shackled down to a rich and pretty but promiscuous wife who flaunts her adulterous affairs, knowing full well there’s little he can do to stop her since her inherited wealth is all he has left to fall back on…

Captain Mycroft (the great Roger Livesey, from The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp and I Know Where I’m Going!), better known as “Padre” to his closest pals, who stoops to impersonating a clergyman even though he’s little more than a cold-hearted con man who’s been caught a few too many times in unspecified acts of public indecency – and with a crate full of late-50s era pornography in tow…

Captain Porthill, a hapless piano tinkler and perpetually bemused gigolo who’s laying low lest his dubious record of war crimes comes under scrutiny and complicates the relatively comfortable but drab existence he’s carved out for himself…

Lieutenant Lexy (Richard Attenborough, director/producer of Gandhi and the crazy CEO of Jurassic Park), electronics expert who was busted for selling secrets to the Russians at the end of the war and now scrapes by rigging slot machines for off-the-books casino operators and the occasional radio repair job on the side…

Captain Stevens, who’s run afoul of social propriety on account of his earlier support of British fascism and more recent suspicions about his (illegal at the time) homosexual inclinations, and pays a hefty fee each month to a blackmailer who’s ready to make his life hell if he doesn’t stay current on his obligations…

… and finally, Captain Weaver, an expert in bomb defusing (and detonation, if the need should arise) whose drunken clumsiness on the job once killed several of his brothers-in-arms. He’s now on the wagon and stuck in a dismal routine as a watch and clock repairman, grimly enduring the incessant chatter of his wife, his senile father-in-law and the blaring television in the background (one of cinema’s attempts from that era to portray TV watching as the pastime of dullards when the industry saw theater attendance dwindle on account of all the tubes being installed in households at the time.)

As for Lt.-Col. Hyde, his grudge is nothing more or less than the fact that he’s aged and advanced to the point of what he considers a premature redundancy. Cut loose from his well-appointed bureaucratic post in the British Armed Forces, he’s out to prove that he’s no man to be trifled with. Hyde and his seven accomplices present a broad and plausible cross-section of mature British manhood at the time, and even though a lot has changed both in England and here in the States since then, the basic male archetypes sketched out in The League of Gentlemen remain broadly relevant. The scene where Hyde first gathers the men together, having successfully lured them in with the promise of that missing half of the fiver and much more to come, is a masterful demonstration in the art of penetrating surface defenses among strangers. Just as each man is about to walk away from the table, feeling insulted at Hyde’s invitation to what clearly appears to be a disreputable criminal proposition, he demonstrates that he has the goods on each of them, calling them out for who they really are, rather than flattering the false front they maintain to the rest of the world. With vain pretenses cast aside, the men quickly bond and, in their consummately jovial British way, get on with the business of planning and executing the perfect crime. They each have their shadowy past, and none lack motivation to a quick strike for the big money and the promise of escape from the dead-end drudgery in which they each find themselves.

The trailer, embedded above, gives generous previews of the main components of the capers that The League of Gentlemen pull off; chiefly, they involve raiding a weapons depot in the guise of IRA insurgents and using those weapons and home made smoke bombs to swipe a pallet full of cash as it’s transferred from armored car to bank vault. While the stunts are pulled off crisply enough, they don’t hold up all that well by today’s standards of high tech ingenuity or muscular slam-bang action. Indeed, the security measures they have to penetrate in each job are laughably flimsy. As a thriller or as as a comedy, which is sometimes how it’s billed, however unsuitably, The League of Gentlemen is strictly middle of the pack, with just a mild degree of suspense and laughs mainly of the kind best appreciated by aficionados of the sardonic “dear old boy” banter that Brits do better than just about anyone else.

Where the film connects most profoundly is in its recognition of how men once valued and relied upon to defend Britain and win the war have now been cast off and expected to resign to their second-rate status. As they move into Central London, past the monuments and landmarks that are virtually synonymous with the power and majesty of the Empire they once swore to serve, the magnitude of their alienation and betrayal of those authorities fully sinks in. It’s a compelling image, and one that sticks in my mind as I see the current political and economic situation in the USA continuing to push a growing number of good men toward the kind of last gasp retaliatory measures portrayed here.

The gentlemen of this league are neither Extraordinary, nor are they Legends. The Justice they seek is admittedly of a most subjective sort, on purely self-serving terms, for grievances that the traditional civic authorities are highly unlikely to validate. And while these Gentlemen are all quite sporting, it’s not quite in the way that our society venerates to the point of being our de facto national religion. In turning the skills they once employed in service to their King and country against the law and order represented by the bank they rob, and despite the ultimate failure of their coup, The League of Gentlemen offer current and future middle-aged guys like me a template for how to stand “present and correct” even after the day of our redundancy has been declared.