I shall have many young kings with round, strong arms.

And when I am tired of them, I shall whip them to death.

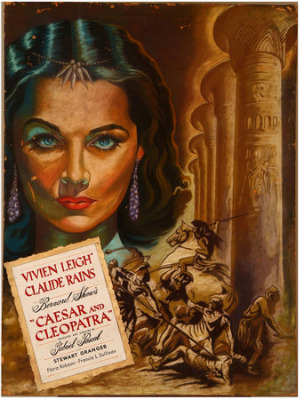

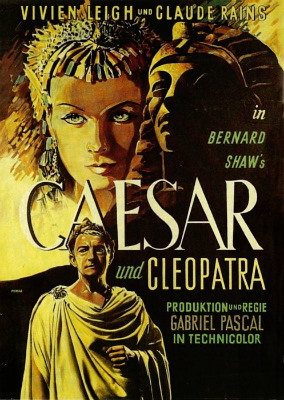

Last week, controversy developed over reports that Angelina Jolie has been cast to take the lead role in a biopic about Cleopatra, the historical Queen of Egypt whose reputation over the centuries has developed to nearly legendary proportions. While I think Ms. Jolie has the perfect blend of beauty, attitude and screen presence to pull off a job that’s served as a platform for silver screen goddesses of decades past, critics take issue with the fact that a Caucasian woman is once again being awarded the opportunity to play one of history’s most noteworthy African female characters. Despite the legitimate argument that Cleopatra’s lineage included European ancestors, I understand the sensitivity of their concern. Similar objections have been voiced about the upcoming The Last Airbender, which also employs a white lead actor to play a child of clearly Asian descent, as well as The Prince of Persia‘s use of Jake Gyllenhaal to play the family adventure film’s Arab protagonist. Even the flap on Twitter stirred up by black actor Donald Glover’s self-initiated campaign to land the role of Peter Parker in a planned Spiderman reboot demonstrates the volatility of this topic. But in my opinion, it takes a certain megastar status to give Cleopatra’s portrayal due justice on the big screen. All questions of ethnicity aside, Angelina Jolie has the screen goddess credentials to follow in the footsteps of Elizabeth Taylor, Theda Bara, Claudette Colbert and (by arrangement with David O. Selznick) Vivien Leigh, the star of this week’s feature in our Journey Through The Eclipse Series, Caesar and Cleopatra.

This 1945 Technicolor spectacle is part of Eclipse Series 20: George Bernard Shaw on Film. The package marks a new angle for Eclipse in that it’s dedicated not to a particular director (though Gabriel Pascal did direct two of the films and produced all three) but instead, a playwright. Shaw was considered in his time the heir apparent to William Shakespeare, and that comparison holds especially true for his play Caesar and Cleopatra, the film version of which bears such a strong resemblance to earlier straightforward movie adaptations of Shakespeare (before it became trendy to put the stories in alternative historical settings.) Similar in look and feel to the Laurence Olivier Shakespeare productions included in the Criterion Collection, Caesar and Cleopatra functions as a kind of companion piece to Olivier’s Henry V in that both were released in close succession, shot in vivid Technicolor and funded by the same tycoon, J. Arthur Rank. Whereas Henry V is regarded as a classic and even an heroic achievement, providing a badly needed rallying cry on behalf of British nationalism in the dark days of World War II, Caesar and Cleopatra hasn’t fared so well. I’ve come across some rather hostile reviews, which you can find by visiting some of the links in this article. I am not without sympathy to some of the objections raised. I had to work a bit to set aside some of the initial skepticism I felt, especially in the early portion of the film. But I’ve come to appreciate it and actually enjoyed my second viewing quite a bit earlier today – so if you’re inclined to check out Caesar and Cleopatra, I recommend that you not give up too quickly. Maybe what I write here will help you hang in there!

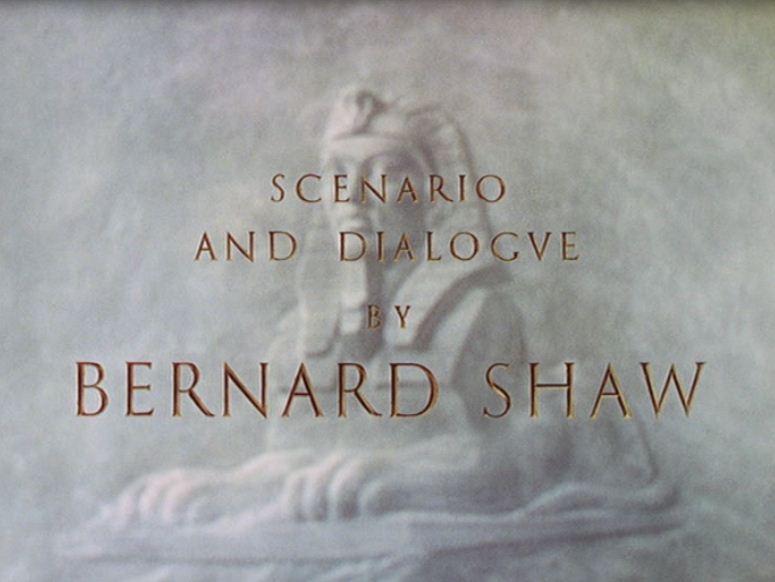

The opening credits, etched in faux marble, with all the Us turned to Vs, give an impression of seriousness and grandeur to start things off. The illustrious name of Bernard Shaw (what happened to “George”?) is given prominent credit for the scenario and dialogue (not merely “written by.”) At nearly 90 years of age, this was Shaw’s last direct involvement with a film adaptation of his works for the stage. I think it’s safe to say that the filmmakers back then assumed their audience had a fair amount of familiarity with the basic facts surrounding the Roman general Julius Caesar, his rival general Pompey, the rift between two factions in Egypt’s Ptolemaic Dynasty and Cleopatra’s seductive powers that ultimately ensnared both Caesar and his younger protege Mark Antony. It may help to read up a bit on all that in order to keep up with the plot and appreciate some of Shaw’s foreshadowing of later events that occurred outside of his play. But a careful viewer will get the needed information by paying close attention. Still, my experience of watching Shakespeare on film applies equally well here – it helps to know the basic outlines of the story going in.

Another lesson from Shakespeare on film fits here too: don’t hold the staginess and artificiality of the characters on screen as a detriment to the film’s overall effect. These movies are not the place to go for convincing portrayals of regular folks just like us. The literary quality of the text, peppered with memorable, epigrammatic quotes, and the mythic dimensions that the two lead characters in particular have assumed in Western culture, put us in the realm of archetypes. In this case, we have Caesar, the aging conqueror, pinned down for the moment in a strange and hostile land, and Cleopatra, the privileged, powerful yet naive young woman who’s just coming into her own as a wielder of power on both the political and sexual level. Each character serves as a canvas upon which Shaw can layer observations of varying degrees of profundity, that the rest of us can relate to in some way or other, either personally as they apply to our own lives, or observationally as we see connections to the lives of others. Caesar’s plight involves the degree to which he exercises his noble inclinations of clemency toward his foes as he reconsiders his war-like ways, while Cleopatra’s character arc transforms her from foolish child into the cunning, seductive manipulator of powerful men that has made her both an object of fascination and a proverbial harlot, albeit one who uses her lack of scruples to achieve notable conquests.

Still, the biggest hurdle for today’s viewers to get over is the blend of colonialist, patriarchal and chauvinistic assumptions that were inherent not only in Shaw’s view of the world but also the culture in which the film was made. Shaw’s play was written in the 1890s. Fifty years later, as Caesar and Cleopatra was being filmed, the legitimacy of European armies descending on North Africa to conquer and impose order in the name of “civilization” was easy to take for granted. As was the inherent sexism of a narrative that, in a very Pygmalion-esque style, emphasized the necessity of an older gentleman’s guiding hand in order to make a “real woman” out of an emotionally vulnerable, even somewhat hysterical young girl. The opening dialog between the worldly sophisticate Julius Caesar and the credulous Cleopatra, all a-tremble under the sway of her silly native superstitions, is potentially noxious enough to cause many viewers less dedicated to the task than me to bail out right away, or take such lasting offense that the rest of the film never gets a chance to work out from under the burden. Caesar treats her condescendingly, a plaything for his amusement, and her easy submission to his mind-games has, at times, an implicitly smutty quality to it.

Likewise, the cavalier mockery of native cultures can be grating. The “humorous” touches of a buffoonish black slave, bugged-eyed and fearful, running around in his underwear screaming “Fly! Fly!” when the Romans approach, or the running gag about the invaders’ inability to pronounce the name of Cleopatra’s head servant Ftatateeta come across as obtuse and boorish more than anything else, but such was the smugness of the old-time boys’ club mentality back then. I suppose it’s good to see with fresh eyes such biases revealing themselves in the guise of entertainment. Caesar’s tutelage of Cleopatra in how to use the threat of raw violence to assert her royal sovereignty is both disturbing and fascinating to behold, especially when it produces such an instantly sadistic response from his young pupil (alluded to in the quote to lead off this article.)

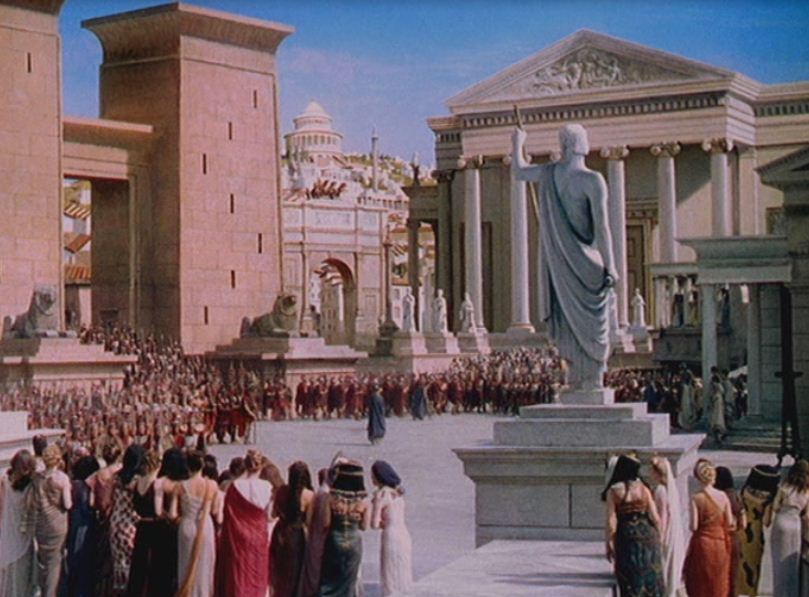

Setting the problems aside then, there’s still plenty to enjoy for lovers of classic, large-scale film sets of the monumental sort, even though they do have that stage-like air of artifice about them and cling rather closely to the conventions of Orientalist fantasy, similar to what you see in The Thief of Bagdad, on the few occasions that attention is given to ordinary Egyptian peasantry. My eyes were pleased by a few beautifully composed exteriors and I’m a big fan of Technicolor too, so that alone validates the price of admission. Less successful are some attempts at “cast of thousands” style spectacle toward the end of the film – the potential for climactic battle scenes on both land and sea was sadly under-exploited, with a feeble montage of very short battle images having to suffice when I was expecting a major throw-down between Caesar’s army and warriors under the command of Cleopatra’s sibling rival Ptolemy and his general Achillus. I get the sense that this production grew kind of exhausted toward the end, which was understandable after learning about some of its setbacks. These included Vivien Leigh’s pregnancy, miscarriage and the early onset of bipolar disorder that would plague her the rest of her life, budget overruns that drew negative attention from the British Parliament (during wartime, no less) and an unplanned relocation of production from England to Cairo (at least they could almost say “filmed on location”!) While there are many fine moments, Caesar and Cleopatra rarely delivers in terms of the sheer entertainment value promised in this trailer:

Due to the cumbersome weight of the spectacle and the general unwieldiness of the whole enterprise, Caesar and Cleopatra failed to recoup its investment, thwarting its creators’ ambitions to go toe-to-toe with Hollywood in the production of blockbuster spectaculars. That was probably a good thing for the overall British film industry, which went on to create some great successes as the careers of David Lean, Powell & Pressburger and many others thrived under more modest cinematic budgets and expectations. Keeping all that in mind then, let’s consider the choice of Vivien Leigh to take the pivotal role of Cleopatra when she did.

In the mid 1940s, Vivien Leigh was the biggest female star in the world, primarily based on the phenomenal success of Gone With the Wind and her iconic performance as Scarlett O’Hara. Her youthful beauty and fiery, impetuous on-screen persona captured the fancy of women and men alike, and she seems to have made a specialty of playing women who transition from times of severe adversity to pinnacles of power, only to face another round of setbacks that force them to rebuild their lives once again. At least, that’s judging from what I’ve seen of her in Gone With the Wind (1939), Caesar and Cleopatra (1945) and That Hamilton Woman (1941), a Criterion release from last year in which Leigh starred with her husband, Laurence Olivier. Cast opposite Claude Rains, who took the male half of the title roles, the two of them make a compelling and entertaining lead couple, though there are only flickers of romantic attraction between them – a dynamic built into the script, not a failure of their screen chemistry in the slightest. On the contrary, these two accomplished actors succeed in building a convincing rapport between older man, seasoned in the accumulation and expansion of power, and younger woman, born to privilege but naive about how to apply her advantages most effectively. Rains is probably most famous nowadays for his supporting role as Capt. Renault in Casablanca, and he’s enshrined in the Criterion Collection as Ingrid Bergman’s sinister husband in Hitchcock’s Notorious.

Other noteworthy contributions include Francis L. Sullivan (the slimy club owner in Night and the City) who plays a similarly ill-fated character here; Flora Robson as Ftatateeta, who’s better known as Sister Philippa in Black Narcissus and as the Stygian Witch (her last performance) in the original Clash of the Titans; Stewart Granger, who telegraphs a coded gay swagger (he’s a dashing, flamboyant, bronze-skinned interior decorator, with a dangling earring and the shortest tunic that censors could presumably allow); and Granger’s future wife, a very young, uncredited Jean Simmons (on the verge of breaking out in Great Expectations) as a fetchingly cute harpist in Cleopatra’s lavish harem, after the queen has completed her inevitable ascendancy to a life dedicated to voluptuous leisure, where all fantasies of Cleopatra eventually lead.

So though its clearly not a cinematic masterpiece by any measure, Caesar and Cleopatra has plenty to recommend it, even if one chooses to give it a “camp” reading. That’s apparently the value discovered by the Worth1000.com website, which takes iconic images and encourages participants to try their hand at coloring them creatively. Click the link for a gallery of takes on one poignant image (though it’s not one that’s lingered over at all in the actual film.) As they say, a picture can be worth a thousand words – I’ll leave you to fill in the blanks however you’d like on this one!

Here's one more link to some fantastic resources about Caesar and Cleopatra from http://www.vivandlarry.com, an extensive archive dedicated to the life and films of Vivien Leigh and Laurence Olivier! http://www.vivandlarry.com/caesarandcleopatra.php

The controversy over Angelina Jolie playing Cleopatra is silly. Those who complain over a Caucasian women playing this “noteworthy African female” are ignorant of history. True, Egypt is on the continent of Africa. But Cleopatra was of Macedonian-Greek descent, part of the Ptolemaic Dynasty, descended from one of Alexander the Great’s generals, after the Greeks conquered Egypt. Thus much as blacks in the US today call themselves African-American, if Cleopatra were alive today she would be labeld “European-African” because she was very much a Caucasian woman who lived in Africa … just as Michelle Obama is a black woman who lives in America.

The controversy over Angelina Jolie playing Cleopatra is silly. Those who complain over a Caucasian women playing this “noteworthy African female” are ignorant of history. True, Egypt is on the continent of Africa. But Cleopatra was of Macedonian-Greek descent, part of the Ptolemaic Dynasty, descended from one of Alexander the Great’s generals, after the Greeks conquered Egypt. Thus much as blacks in the US today call themselves African-American, if Cleopatra were alive today she would be labeld “European-African” because she was very much a Caucasian woman who lived in Africa … just as Michelle Obama is a black woman who lives in America.

The controversy over Angelina Jolie playing Cleopatra is silly. Those who complain over a Caucasian women playing this “noteworthy African female” are ignorant of history. True, Egypt is on the continent of Africa. But Cleopatra was of Macedonian-Greek descent, part of the Ptolemaic Dynasty, descended from one of Alexander the Great’s generals, after the Greeks conquered Egypt. Thus much as blacks in the US today call themselves African-American, if Cleopatra were alive today she would be labeld “European-African” because she was very much a Caucasian woman who lived in Africa … just as Michelle Obama is a black woman who lives in America.

J. Arthur Rank did not finance Olivier’s “Henry V”. He financed Olivier’s “Hamlet”. Fillipo del Guidice financed “Henry V” , and his company Two Cities Films released it.