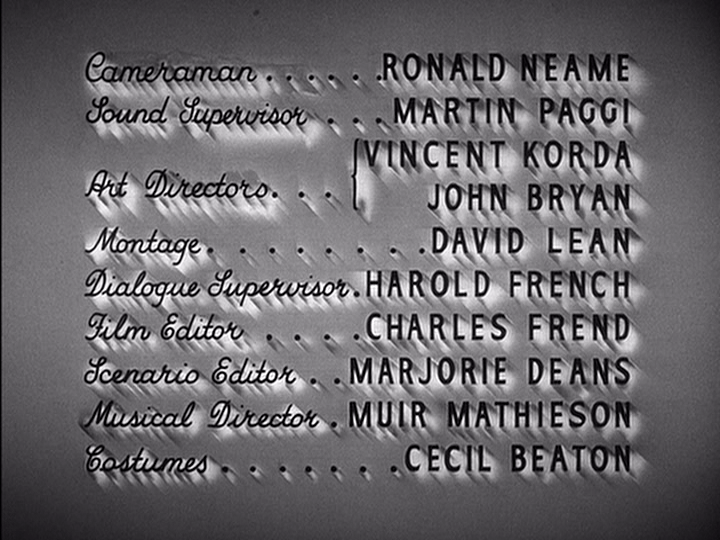

Last week on my Criterion Reflections blog, I wrote an essay about Tunes of Glory, a 1960 film by Ronald Neame, in which I said nothing at all about the director other than citing his name as such. My thoughts on the film took me in different directions than dwelling on Neame’s “invisible camera” style of movie making, which I suppose is appropriate enough because he’s probably the least pretentious of all the directors represented by multiple titles in the Criterion Collection. Neame does little in his work to draw attention to himself, firmly believing that his task is to draw audiences into the story to the point where they forget that they’re watching a film. His is an approach I admire, even though I also appreciate the more deliberately meta style that our podcast spent the month of September discussing in films like Man Bites Dog and Symbiopsychotaxiplasm. Different movies for different moods, y’know? But to make up for my unintentional slight of ignoring Ronald Neame by discussing all sorts of other things about a movie he considered his personal favorite of all that he made over the course of a lengthy and honorable career, I decided to give him a bit of attention for work he did nearly two decades earlier, when he worked as the cinematographer (as credited on the DVD)-slash-cameraman (as credited in the film) on Major Barbara.

Of course, Major Barbara‘s biggest claim to fame, and the reason it was chosen for inclusion in Eclipse Series 20: George Bernard Shaw on Film, has little to do with Neame, and much more to do with its authorship by the man many consider to be the most important British literary figure of his era (roughly the late 19th to early 20th century.) Shaw is a complex and fascinating figure – a brilliant wordsmith, creative and prolific thinker, abounding in all sorts of ideas aimed at reforming society, bettering humanity and, should those lofty ambitions fail, finding plenty to laugh about it all in any case. As a highly successful playwright, he withstood the pleas and temptations of allowing his works to be adapted for the screen for quite a few years, but finally, somewhat inscrutably relented in his old age due to his apparent admiration for eccentric mystery man Gabriel Pascal, who had befriended Shaw as a young passerby on the spur of a moment and parlayed that chance encounter into a highly improbable film deal many years later. Pascal seized the opportunity, producing Pygmalion, which earned Academy Award nominations and won a Best Adapted Screenplay Oscar for Shaw and his co-writers in 1939. That success paved the way for more Pascal adaptations of Shaw’s plays, and Major Barbara was the first, and easily the most successful of the three that followed. The failed would-be blockbuster Caesar and Cleopatra and the uneven whimsical satire of Androcles and the Lion are the other two films featured in this set, though the most famous and financially lucrative version of Shaw on film continues to be My Fair Lady.

Shaw’s direct involvement (at his insistence, of course) in the production of these films adds a unique imprimatur to the variations that exist between his stage plays and their cinematic realizations. Enough for now about Shaw and Pascal. I’m here to talk about the film, and more specifically the platform it offered for young talents like Ronald Neame and David Lean to learn and refine their craft. You can see their names bracketing another familiar one from that era, Vincent Korda, one of the famous Korda brothers who were so prolific in the British cinema of the 1930s and 40s. Major Barbara often resembles a filmed stage play, which makes sense given its pedigree, and there are many winning aspects to seeing the actors do their dramatic/comedic work in something resembling its original theatrical setting. Wendy Hiller returns for another take on Shaw after her performance as lead ingenue in Pygmalion, and Rex Harrison makes a suitable replacement for Leslie Howard as the leading man for this film. Add to that the debut of Deborah Kerr (whose impressive triple-role casting in The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp was recently re-issued by Martin Scorcese’s Film Foundation in a new print), Robert Newton’s amusing Cockney thuggery and a vintage assembly of some of England’s finest character actors, and you’ve got an evening’s worth of splendidly intelligent entertainment, assuming that the dated cultural references and dialogue-heavy pacing don’t weigh to heavily on your movie-watching experience. As I hinted above, this is the kind of film that you may have to be in the right mood for to fully appreciate. This clip might be a useful gauge to determine your personal readiness to have the Major Barbara experience (… or you could just watch it on Hulu Plus):

The clip is from very early on, the only one from this version of Major Barbara that I could find on YouTube. It sets up the basic conflict, between the titular character, daughter of a controlling high-society mother and an arms merchant father who’s estranged from his family. Barbara, the oldest of three children, has foresworn the privileges and comforts of the fortune she’s heir to in favor of a missionary career with the Salvation Army. She’s an idealist who believes she’s found the secret to lasting inner peace and true happiness, a secret she’s all too happy and quite confident to share with any who will listen to her appeal. Her public square pitch brings her into contact with Adolphus “Dolly” Cousins, an intellectualized dilettante who takes Barbara up on her offer, partly as an intellectual experiment to satisfy his curiosity and partly because he finds this well-bred, impeccably earnest woman attractive beyond his ability to rationally explain.

The central conflict between Barbara’s sincere piety and Dolly’s shrewd skepticism is further aggravated by the intrusion of Andrew Undershaft, the aforementioned weapons trader who abruptly introduces himself to his adult children at the invitation of his estranged wife one evening and sees in his oldest daughter a worthy foil to test out his own theories on the underlying motivations and obscuring delusions that propel humanity forward to an unknown destiny.

Undershaft is a consummate cynic and materialist, a rich industrialist know-it-all whose quick wit and authoritative presence tends to bend and persuade others to see things his way – in short, he’s a reliable spokesman for Shaw himself. Firmly convinced that Barbara is wasting her considerable gifts and potential in a short-sighted gospel ministry to the poor and marginal elements of society, Undershaft takes it upon himself to isolate and attack the weak spots in Barbara’s belief system. For her part, Barbara sees him as intriguing but corrupted, and she’s appalled by her father’s exploitation of violence and destruction as the vehicle by which he earned his fortune. Using his considerable wealth to ply significant compromises from Barbara’s commanding officers in the Salvation Army, he succeeds in driving a wedge between her uncompromising principles and the more pragmatic considerations made by her superiors in accepting his money. The flurry of exchanges between Undershaft, Barbara and Cousins, a refined scholar of classical Greek philosophy and literature, posits the three driving forces that set the terms of Shaw’s civilized British milieu – commerce, religion and higher education – against each other in an extended verbal joust that runs the length of the film.

But there’s more than just a tussle within the social uppercrust going on, as we see various representatives of the lower-class also having it out with each other. Deborah Kerr as Jenny Hill, a teenager just converted and full of zeal, and Robert Newton as Bill Walker, a ruffian and hell-raiser who’s convinced that the Salvation Army is just a manipulative scam, stand out but are just two examples of the commoners that Shaw turns his attention to in rounding out his social portrait of Edwardian-era England.

The convolutions of plot and characters are such that a thorough review requires more time and attention to detail than I’m able to give Major Barbara at the moment. For those inclined to make the translation from the film’s quaint, old-fashioned setting and our present day, I think its commentary on the influences that money, spirituality, situational ethics and human passions all exercise on each other holds some relevance in our contemporary debates on how best to address questions of economic justice and repair the shreds and tatters of our worn-down social contract. Of course, I don’t hold out any hope at all that our politicians or pundits would bring an intellectual sharpness roughly equivalent to Shaw’s into the conversation. That’s asking just a bit too much of the kind of leaders our culture seems capable of putting forward these days.

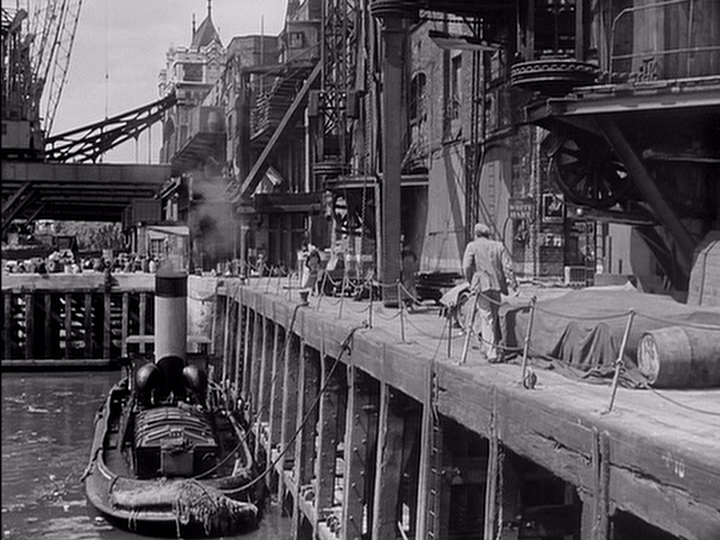

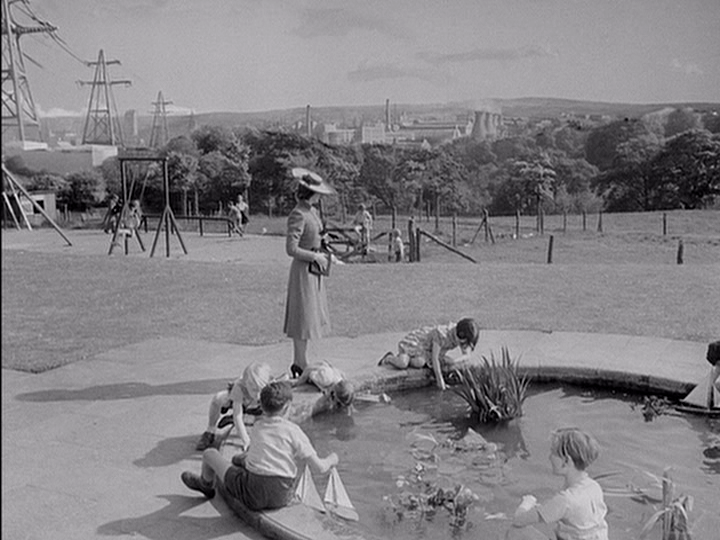

So with little confidence that a movie like Major Barbara, or the ideas it espouses, would be able to contribute much to popular discussion of the broader issues of our times, let’s just look at some of the nice images and atmospherics that Neame, Lean, Korda and even Gabriel Pascal himself were able to leave behind for our appreciation. While Lean went on to become among the greatest epic film makers of all time, Neame’s reputation is understandably more modest. Pascal was more of a deal maker and creative visionary who delegated more of the technical details to his crew – it seems clear enough that his role as producer was more substantial than what he contributed as director. The set designs, lighting and studio creation of a rough-hewn environment of West End London helped prepare Lean for his memorable work years later in transporting us to the world of Charles Dickens in his adaptations of Great Expectations and Oliver Twist (both of which were produced as well by… Ronald Neame!)

Neame’s camera work is, for the most part, fairly steady and unassuming, mostly beholden to the demands of capturing the actors as they deliver their lines, but there are some segments toward the end, when Barbara makes her agreed-upon tour of her father’s munitions factory and the pleasantly manicured company town where the workers are housed, where we’re able to get off the sound stage for awhile. The fearsome conditions of the steel foundry in particular are pretty vivid, as molten metal and showers of sparks come into dangerously close proximity to the hard-working men who toil in those hellish conditions.

My bottom line on Major Barbara, and the other films in this set, is that they’re of vastly more interest to anyone curious about the ideas and career of George Bernard Shaw than to those who are looking for great original works of cinematic art. The coincidence that they were crafted by some young apprentices who went on the bigger and better things, and that they featured some substantially talented actors as well, adds to their appeal. As for the choice that Shaw somewhat forces upon the viewer, to side with the smug robber-baron Undershaft who both gets the last word and the apparent allegiance of Barbara and Dolly at the end of it all, I’m not so inclined to agree. Even in as sophisticated a debate as Shaw framed here, his presentation of the issues seems skewed and simplistic. Thought provoking? Yes indeed. A sly and acerbic send-up on some of the prevailing presumptions of its time? Sure, I’ll acknowledge that. But even though Major Barbara was filmed in 1941, when Great Britain’s weapons manufacturers played a crucial role in the eventual defeat of Nazism, times have changed. And I’m just not willing to hand authority, respect and a justified sense of entitlement back over to the masters of war quite yet, not if there’s anything I can do to stop them, or at least slow down their march toward destruction a little.