The USA just got through its annual observance of Thanksgiving, a holiday that somehow morphed from a national moment of reflection for good things experienced over the past year into an all-out orgy of shopping and cost-cutting dedicated to generating a massive influx of retail revenue across our land.

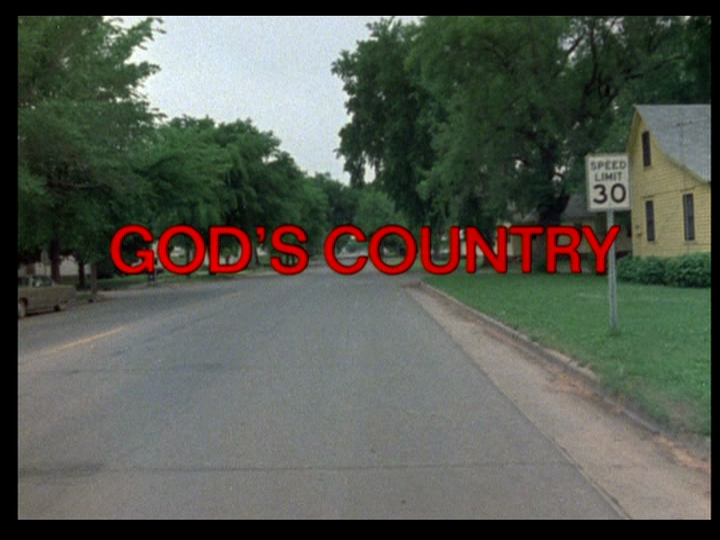

Given the background of heartland sentimentality that prompted the occasion way back when and the more recent emphasis on its economic implications, God’s Country, from Eclipse Series 2: The Documentaries of Louis Malle, seems like the perfect fit for my weekly column featuring one film from that collection.

Shot mainly in 1979, 20 years and counting since Louis Malle first made a splash in the international cinema scene with Elevator to the Gallows and a slew of other landmark films over subsequent decades, God’s Country represents a small-scale (and friendly) culture clash between the urbane European sophisticate cineaste and residents of Glencoe, a small Minnesota farm town.

Malle was commissioned by the Public Broadcasting System (PBS) to create a documentary about the American phenomenon of indoor shopping malls but abandoned this project due to aesthetic obstacles that impeded his progress: he couldn’t overcome his revulsion from the muzak he heard over the intercom system. But since he was on site with film crew at the ready, he set out to find other subjects of interest.

One afternoon, he happened to be driving down the road when he spotted a lush garden in someone’s front yard. He stopped to get some shots, met a lovely old woman in her mid-80s who was tending to her vegetables and flowers, and after a few minutes of conversation, decided to make the life of this community his focal point. A county fair happening around the same time gave him a nice visual and musical introduction to the film, and from there, he was off and running.

As he showed in his earlier documentary (reviewed here last summer) Vive Le Tour, Malle has a gift for capturing the subtle stories found in ordinary street scenes. There, his context was the annual running of the Tour de France and he roamed the French countryside tracking not only the racers but the ordinary citizens who provided an audience for the competition.

Here, he took his time exploring the day-in, day-out routines of a small community out in the vast expanse of flyover country that seldom gets much attention in the movies compared to America’s big cities and coastal regions. Though Malle had traveled the world over the course of his career and produced a pair of highly respected documentaries in India, we can hear through his off-camera comments and questions a genuine tone of amazement and curiosity as he learns more about the mysterious combinations of experience and belief that propel Glencoe’s citizens through their lives.

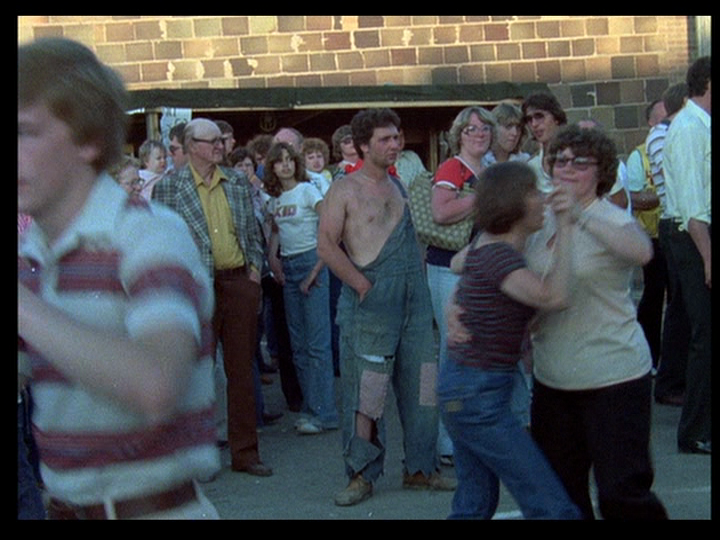

The first half of the film serves as an overview of Glencoe’s social customs and culture, as we move from the fair to a church service, an interview with a local pastor about the state of marriage in the community, and a sardonic examination of the town’s “one devastating passion” – lawn mowing. Malle is obviously not too accustomed to areas where common home owners manage wide open spaces and feel the pressure to keep their lawns inconspicuously trimmed and tidy.

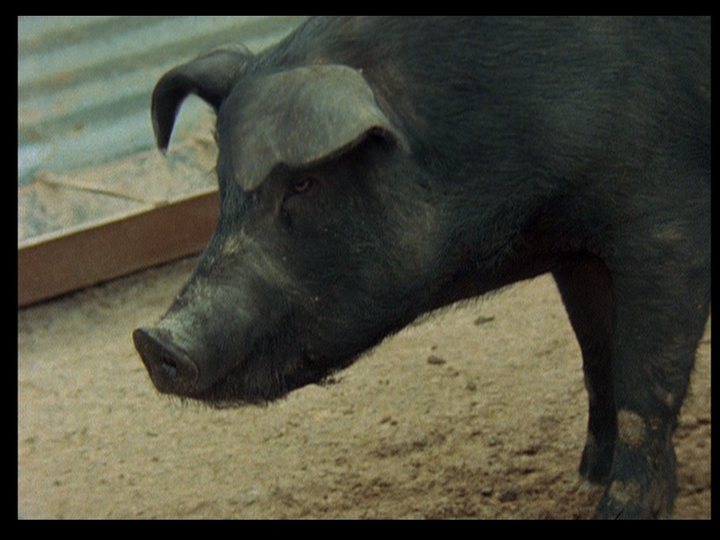

This early section of God’s Country focuses more on recreational pastimes like softball, but soon moves into a look at the economic engines that keep Glencoe prosperous: primarily farming, both crops and livestock, with the residual support services in place to keep everything humming along smoothly: police, banking, the local pharmacy and a Dairy Queen franchise to keep the populace fed and refreshed.

But Malle’s gaze into the life of Smalltown USA becomes ever more incisive and unsparing as his film gathers steam. An interview with a local pig farmer swiftly escorts us through the process of how sections of the cute grunting barnyard beasts wind up in tidy plastic wrappers on supermarket shelves. He spares us the more revolting displays of guts and gore (this was a made-for-TV production, after all) but manages to nudge most sensitive viewers that much closer to vegetarianism anyway. And then an earnest exchange with a sincerely likable young family drags the town’s latent and overt racism to the surface.

It’s a revealing exchange that I have a hard time imagining would unfold so openly and candidly these days, at least not on film. People who hold the kind of prejudice we hear spoken of in God’s Country nowadays have become more skilled at deflecting their honest beliefs when pressed on the issue.

Given Malle’s more liberal views on any number of social issues, and his obvious success in the world of show business, it doesn’t take him too long to find the local alternative arts scene. In this case, it’s a small theater company, run by the wife of one of Glencoe’s more prominent attorneys, whose son served time in federal prison for his antiwar activism back in the Vietnam era.

Malle’s interactions with this group exposes the not-so-conservative side of small town life and the struggles local non-conformists go through as they look for a place to fit in. This section of the film contains several of my favorite interviews, particularly the extended talk with Jean, a woman in her late 20s who bravely recounts some of her past mistakes and struggles and gives a remarkably open account of where she stands on some sensitive topics that, by her own admission, she hadn’t really thought all that much about!

After this exchange, God’s Country takes a definite turn toward more serious, even grim, issues as Malle visits Glenhaven, a nursing home where the town’s elderly citizens are sent off to die in slow, sanitized, quiet dignity. One resident, interviewed while out getting his exercise, expresses his preference to be in the graveyard over where he currently stays.

An old woman, bound to her wheelchair, stares intently into the camera, offering the viewer ample opportunity to contemplate the life experience that brought her to that moment and peer back into the depths of her gaze to find signs of meaning and purpose ourselves.

But before things get too heavy, Malle lightens the tone by ushering us into a wedding ceremony featuring two teenagers, still not old enough to legally drink beer at their own wedding – there’s even a scene of the groom getting carded and refused because he can’t produce an ID!

It’s impossible to resist drawing the conclusion that Malle the Frenchman took more than a little delight at putting the bumpkin-like dancing and cavorting of these descendants of German settlers on the screen. Though the wedding guests are clearly having a good time, they look kind of goofy cutting it up on the floor in their vintage 70s wardrobe.

A fortuitous series of delays in finalizing the production of his documentary gave Malle the opportunity to return to Glencoe six years after the bulk of the footage was shot, in 1985. Upon his arrival, he delighted to see the same old woman, now 91 years old, still tending her garden.

Other citizens had moved on, including Jean, the woman interviewed above. But those who remained indicated in their remarks that all was not well in God’s Country. A collapse in agricultural prices had pressed small family farms to the brink of bankruptcy, and the locals were getting impatient, with talk of organized violence rumbling through their conversations.

Given the current plight of the American economy and the recent political ascendancy of right wing ideologues who play on fear and prejudice to advance their cause, I found it quite fascinating to hear a small businessman of 1985 go on a tear against the patron saint of today’s conservatives, Ronald Reagan himself, who presided over a massive expansion of the federal deficit over the course of his presidency. The guy invokes some anti-Jewish conspiracy theories and cites George Washington as a role model. He was Tea Party when Tea Party wasn’t “cool”! Here’s a quote:

“It takes a very stupid man not to be able to see that when he took office, the national deficit was 300-400 million, now it’s 2 trillion! We have a movie star president who can convince a lot of people a lot of the time. He can tell the world the deficit’s five times higher than it ever was, but it’s alright!”

I wonder how today’s teabaggers would spin that one…

On a personal level, watching God’s Country was an amazing experience for me. I graduated from high school in 1979, and though I was living in the San Francisco Bay area at the time, my childhood upbringing and family roots in Michigan were captured quite vividly in Malle’s images. It reminded me so much of what I rebelled against in my teens and early 20s, and what I gradually returned to (with a few modifications) after my wife and I had kids. I married into a farm family that could have interchangeably fit right into the Glencoe scene.

My mother-in-law came from Edgerton, another Minnesota farming community not all that different than the one in the film, and her sons, my brothers-in-law and their kids all live out in the countryside south of Grand Rapids where I now reside in a more suburbanite environment. Malle brilliantly treads a very fine line that reveals both the virtues and cultural blindness of this and similar “salt of the earth” communities without stooping to exploitation or condescension.

Malle’s appreciation and fondness of the people he meets in this journey comes through in the respect he shows by letting them speak for themselves and in the underlying integrity and optimism that supply their motivation even in the face of adversity. I don’t get the sense that many people have seen this documentary in recent years, but in its subtle critique of the heartland values that people of this region take so much pride in, Malle presents a message that deserves to be heard and speaks relevantly to our times.

The final words of the local attorney, expressing confidence that the culture of greed he saw taking root in the mid-80s would ultimately not be embraced by the American people, sadly seems a bit naive, judging by how much wider the gap between rich and poor has grown since that time. But in the spirit of hope that has brought our fellow citizens through times of strife and hardship over the years, I’m willing to stand alongside him and help put his message out there for others to consider. Perhaps there still is time to put the greed behind us and do what we can to work for the common good… in God’s country (or maybe even the whole wide world.)

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)