As some of you may know, my personal blog, Criterion Reflections, serves as my on-going journal (over 2 1/2 years now) of watching all the Criterion Collection films in their order of chronological release, beginning with 1921’s Nanook of the North. This past week marked a milestone of sorts as I finally worked my way through the 1950s and just posted my first review from 1060, of Georges Franju’s Eyes Without a Face. Next in my queue is a late-career masterwork by Mikio Naruse that was for several years the only title from his long career available legally available on DVD in the USA, When a Woman Ascends the Stairs. Criterion remedied that situation earlier this year with the release of Eclipse Series 26: Silent Naruse, compiling the director’s five extant silent films in one handy box.

In recent weeks, they’ve done us all a service by importing a few mid-career titles into their ever-growing catalog of Hulu Plus exclusives. Being that When a Woman Ascends the Stairs is regarded by those in the know as Naruse’s crown jewel, the culmination of a filmography that’s probably more admired in reputation than actually well-understood by the majority of cinema buffs, I think it’s important for me to take a little extra time familiarizing myself with the path that Naruse took to arrive at that pivotal moment. So I’m planning to work my way through as many of his other films as I can before settling in to watch that woman ascending those stairs sometime later this week. I’d like to avoid some of the drawbacks that come with watching the output of a director at his full maturity and jumping to conclusions of what they were trying to say without the full benefit of watching the career unfold. That’s what led me to pigeonhole Kenji Mizoguchi as a creator of Japanese historical costume epics based on watching Ugetsu and Sansho the Bailiff before I’d seen any of his earlier films based in a grittier urban contemporary context.

So for this week’s column here, I’ve chosen Every-Night Dreams, a selection that seems to share a few common traits with When a Woman Ascends the Stairs. Both are centered on a female protagonist who’s forced by pragmatic concerns to work in a Tokyo ginza bar, against the dictates of her conscience but with few if any realistic alternatives, due to the course that her life has already taken. I could have just as easily chosen the other film on this disc, Apart From You, but I’ll save that for some other time. As I’m confident I’ll discover myself as I watch more of Naruse, he reportedly didn’t stray too far from this kind of narrative once he settled into his genre groove. Some would consider his genre to be “melodramas for women,” which is certainly a plausible label to tag him with. However, I think it’s more accurate to regard him as a social realist who happened to put women at the center of his stories, but in actuality rendered his male characters with more nuance and subtlety than the villainous scoundrels that one might surmise based on a first, casual impression.

In Every-Night Dreams, the story focuses on Omitsu, who we meet in the opening moments as she’s returning to her neighborhood after a few weeks out of town. She’s quickly greeted by a couple of carefree sailors who relish the chance to offer her a smoke in exchange for some mildly flirtatious banter… until it turns out that one lacks the cigarettes and the other lacks a light. Omitsu rolls with their clumsy come-ons effortlessly, clearly used to being hit on by lonely guys without taking offense at their occasionally oafish behavior.

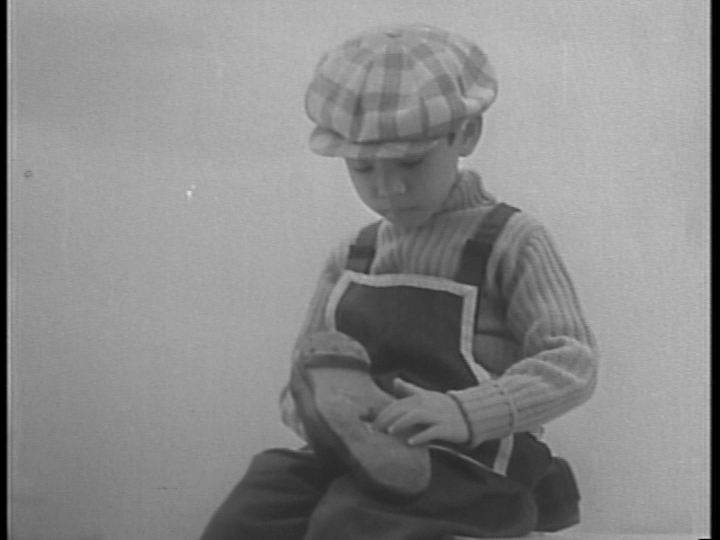

Even though she’s quite pretty and in different circumstances might have landed in a more comfortable station in society, Omitsu has clearly been toughened up a bit by some hard knocks in life. She smokes openly, walks the streets with a slightly immodest strut and can deliver the saucy repartee that’s necessary to keep the wolves at bay. All these skills have proven necessary in her employment as a barmaid in the waterfront dive that provides her sustenance. And not just hers. Omitsu has a son, Fumio, the half-pint remnant of a relationship gone bad, as there’s obviously no father around to help raise and support the boy.

This video clip offers a skewed-angle glimpse of the scene where Omitsu first arrives in the apartment of the family to whom she’s entrusted Fumio, to keep an eye on him while she was away from home. It was taken from someone’s camcorder, obviously. Despite (or perhaps because of) it’s bootleggy origins, it’s the only clip from Every-Night Dreams that I could find on YouTube, so take it for what it is. Or subscribe to Hulu Plus and watch the whole thing!

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-yvUIWtYDQM&version=3&hl=en_US]

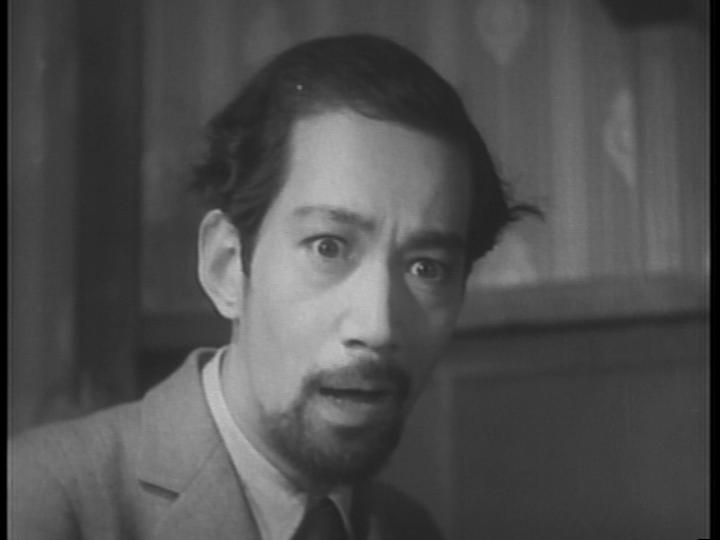

Though our first impression leads us to believe that Fumio was the product of some after-hours liaison between Omitsu and some sailor just passing through, we soon learn that his father Mizuhara is still married to his mother – but he’s been out and about, up to who knows what for several years. His return home is as unwelcome by Omitsu as it is unexpected.

There’s no doubt that Mizuhara has been your prototypical deadbeat dad, and he’s the first to admit it, apologizing without much prompting, recognizing that he has a long way to go to make things right between him and his estranged wife. But he wants to do that – for her sake, for his sake, and most of all for the sake of his son.

Omitsu isn’t easily persuaded though, berating her kind-hearted and generous neighbors for fussing over him, going so far as to call Mizuhara ‘the enemy!” Wary of letting down her guard and getting burned again, she turns a deaf ear to his entreaties and sends him packing on his way. Why risk bringing more hassle and suffering into an already difficult day-to-day struggle to stay afloat?

The shot of Mizuhara’s feet slowly shuffling across the floor and down the stairs is just one indicative example of Naruse’s creative flair with the camera. Numerous zoom-ins and sinuous tracking shots create compelling moments of discovery and realization, both internally for the characters of Every-Night Dreams and for viewers who appreciate the nervy execution and sheer beauty of Naruse’s cinematic techniques. The impressions they make are vivid enough to overcome the far-from-pristine condition of the source material.

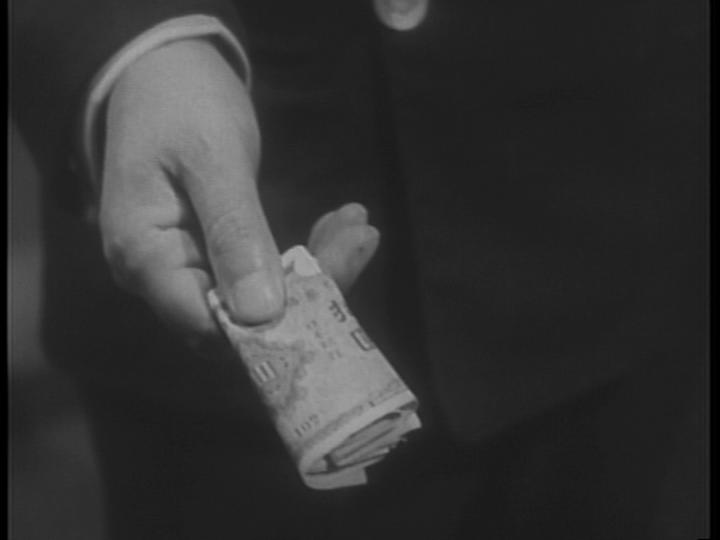

But Omitsu also has to face other tough realities. She needs to make money, and for a woman of her checkered past, the options are terribly limited. No respectable man would take her for a wife, though relatively powerful and prosperous men are happy to “take good care of her” if she’s willing to take the cash with a few sexual strings attached. One of them, a roguish captain, is played by the stalwart Takashi Sakamoto, well known from Ozu’s films of this period and one of the most instantly recognizable faces from this era of Japanese cinema.

The combination of financial hardship, concern for the lack of a father figure for Fumio’s upbringing, and slim hopes that Mizuhara just might turn things around after all cause Omitsu to relent. She lets her husband move back in, taking his flurry of vows to get a job with a grain of salt but wishfully optimistic that things just might turn out different this time. But she quickly sees that Mizuhara hasn’t been able to move past the patterns of idling and floundering that characterized the earlier phases of their relationship, as he’s more content hanging out and playing with the kids instead of securing that steady job that will put the young family back on their feet.

Naruse employs a few themes and gags that we first saw in Flunky, Work Hard, the earliest film in Silent Naruse, including a little visual fun with a hole in the sole of a working stiff’s shoe, and grown-up men who make fools of themselves in order to amuse neighborhood children. It makes me wonder how much of this self-quotation we would have seen if the other dozen now-lost silents that he made would have been preserved.

Even though Mizuhara proves to be a man with deep and insurmountable flaws, Naruse and actor Tatsuo Saito, another Ozu mainstay, still manages to evoke enough empathy for the lanky, aimless sad sack that most in the audience will regard him with something less than undiluted contempt. His heart seems to be in the right place, but he’s as beaten down and hard-pressed by adversity and injustice as the women that Naruse typically dwells on. Mizuhara gives the job search a sincere effort, but he’s so obviously scrawny and easily fatigued that prospective employers hardly need give him a second glance; Japan is in the midst of a crippling economic depression, and the supply of cheap common laborers is far greater than the skimpy demand.

As if the situation weren’t already exasperating enough, Naruse again resorts to one of his favorite ploys, a severe but non-fatal pedestrian car accident that injures Fumio and throws the fragile family and social circle into chaos. On top of the grinding poverty, now they need to raise money for medical treatment. I’ll leave you to see for yourself the desperate measures that Omitsu and Mizuhara resort to, but as you can probably already guess, it doesn’t end well.

In roughly the same length of time that a prime-time TV show takes to tell its story, Naruse uses the hour allotted to him to open the eyes of his audience to the plight of ordinary poor people whose marginal status somehow renders their pain and sorrow of lesser importance than the travails of the respectable middle class. Japan was already on its way to fully manifesting the fascist and imperial tendencies of their feudalistic past, so it could be said that Naruse’s social critique was unsuccessful in swaying the minds of his peers. But his sensitive and perceptive ability to capture small nuances of emotion through subtle expressions and words left unsaid effectively transcend the time and place in which his films were made.

Like his later Street Without End, Naruse escorts us into the world of a young woman determined to overcome the malignant forces stacked against her. We see her endure a few crises and demonstrate her resilience, but as we depart back to the stability and comfortable routines of our own lives, we really don’t know what her future will hold. We just understand that it won’t be easy but we’re left with the sense that whatever suffering she and Fumio have to endure will only strengthen their resolve and fuel the aspirations for eventual relief as they seek the solace of their Every-Night Dreams.

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)

2 comments