Happy New Year greetings to you all, CriterionCast readers! In searching through my stack of Eclipse DVDs, I could find no better offering for the occasion than the title Three Resurrected Drunkards, from Eclipse Series 21: Oshima’s Outlaw Sixties. It incorporates both of the main themes of the just-concluded holiday – renewal and revelry – although I have to say, there really isn’t much that I found within the film that refers to drinking, and even its alternate title, Sinner In Paradise, doesn’t really serve to explain all that well what you’ll find in this abruptly confrontational late-60s exercise in subversive satire by iconoclastic director Nagisa Oshima.

Coming off a week in which I delved head-first into the stirring but traditional narrative approach of Raymond Bernard’s Les Miserables, making the fast pivot to Oshima’s style was enough to induce a case of cognitive whiplash.

But a couple of viewings of this oddball gem helped me make the adjustment, at least to the point where I can say that I appreciate the effect of what he was going for here, even if I still feel like I don’t totally grasp the full extent of what Oshima had to say.

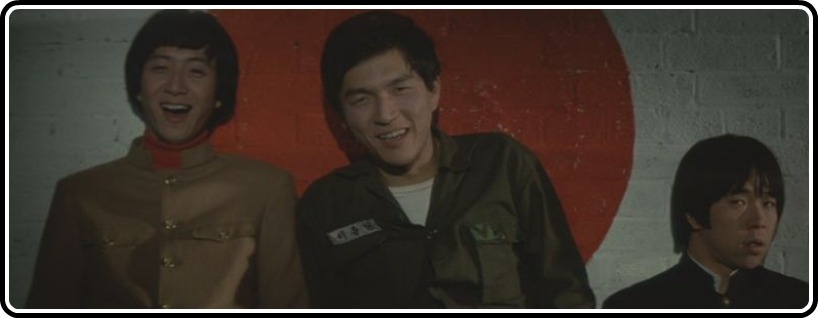

Three Resurrected Drunkards splashes onto the screen with all the zest and exuberance that films featuring 1960s pop stars are renowned for, examples of which include the Beatles’ A Hard Days Night and Help! or the Monkees’ Head (each of which boast some sort of Criterion connection.) A trio of young Japanese men in their early 20s amble onto a sandy beach on Japan’s southernmost island, where they take turns pointing fingers at each others heads as if they’re holding guns and about to shoot. After a few minutes of this horseplay, they decide to strip down to their undies and go for a swim.

While they’re out frolicking in the waves, a strange disembodied hand reaches up from beneath the sand, oblivious to the threat of high voltage underground wires, and snatches away two of the military uniforms they were wearing. The thieving hand replaces the stolen garments with clothing that belongs to a pair of Korean stowaways who are seeking refuge in Japan and escape from the obligations that their Korean citizenship imposes upon them – namely, military service in Vietnam that their government acquiesced to on their behalf due to American pressure in the 1960s.

When the guys return to get dressed, they’re alarmed to discover their new wardrobe, but lacking other alternatives, the two who had their clothes snatched have no choice but to dress up in what was left to them.

This leads into a wacky sequence of events where they’re mistaken for illegal Korean immigrants, chased by Japanese police and ultimately accosted by the two refugees themselves who want to kill them while dressed in foreign garb, thus confusing the authorities and securing their own smooth transition into Japanese society.

But that brief summary of the plot of Three Resurrected Drunkards doesn’t really provide an adequate introduction to the film, because the disclosure of a conventional narrative is secondary to Oshima’s concerns here. The movie really serves as a setup to a larger, more serious point that he’s trying to make, even as he employs an aggressive and artistically risky technique to convey it.

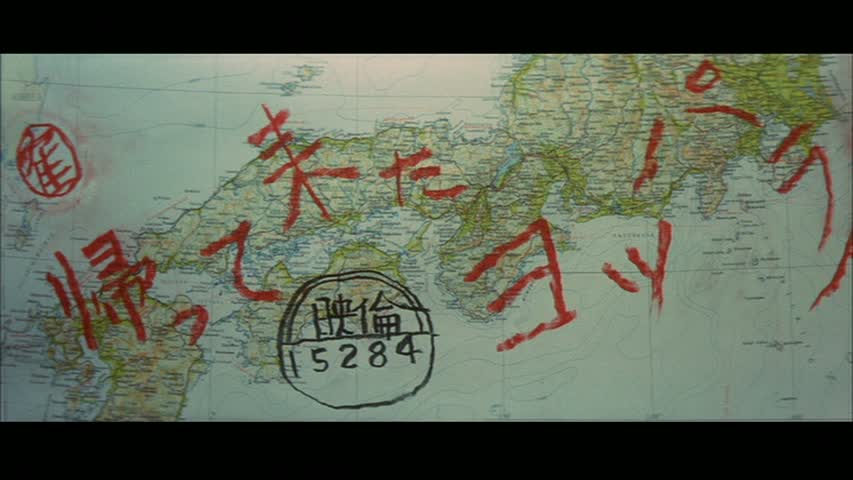

Three Resurrected Drunkards comes across as a loose, absurd, surrealist comedy for most of its running time, with a few brief excursions into documentary and Godardian agitprop along the way. Here’s the theatrical trailer. Watch it and try to imagine something like this coming to your neighborhood cineplex any time in the foreseeable future. Then think about what kind of guts it took for Oshima to turn this into his studio as their latest bid to cater to “the youth crowd” circa 1968:

Be careful with that slightly sped-up theme song though – it’s highly infectious! Once it settles into your consciousness, you’ll need something equally strong and contagious to get it back out.

The resurrection mentioned in the title occurs at the halfway point of the film’s brief 80-minute runtime, just after the three men have come into contact themselves with the level of contempt, suspicion and callous disregard that Koreans are subject to in Japanese society. At this point, the story recapitulates upon itself, as scenes from the beginning of the film are mimicked with subtle changes from what occurred the first time around.

The three young men go through their motions with a deja-vu like awareness that they’ve been here before and are now given the incredulous opportunity to retrace their steps and get it right the second time around.

But even this serendipitous opportunity fails to result in a perfectly happy scenario, as they find themselves pursued by the same pair of Korean outlaws, as well as a man and woman who present as father/daughter and husband/wife at varying intervals, who dogged them in the first half of the film.

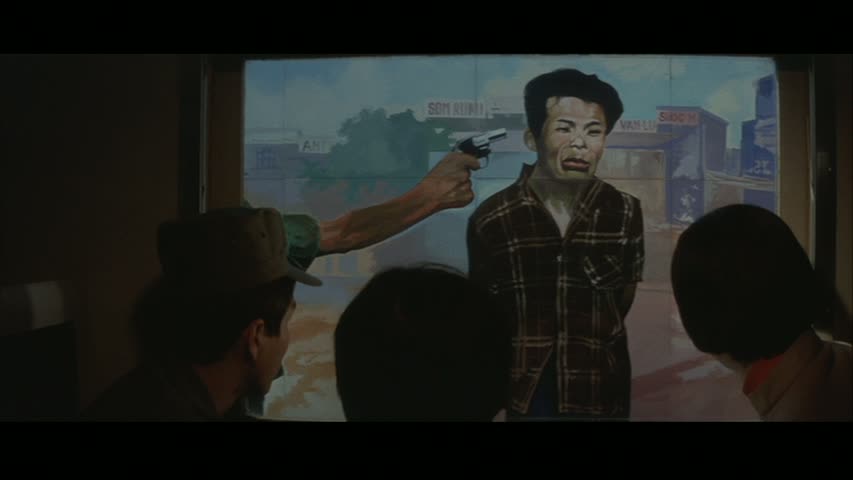

Despite their enhanced sense of empathy with the plight of Koreans, the Three Resurrected Drunkards find themselves in a Twilight Zone-like nightmare scenario, trapped and hunted down, facing the grim prospect of assassination as captured by the famous Eddie Adams photograph that was taken and widely distributed in 1968, the same year that this film hit Japanese theaters.

Oshima’s film is best seen (imo) as a snapshot of its moment, as the frustration and hostility generated by the American war in Vietnam came to a peak in Japan in particular. Though I obviously don’t share Oshima’s frame of reference at this point in time, watching this film gave me a tangible sense of the outrage that was felt in other nations as the horror of that war grew increasingly hard to ignore.

Much like when I watched Pierrot le fou‘s antiwar scenes, I was struck by the realization that the wars of the USA don’t happen in a void involving merely my country and the nation we’ve invaded. The rest of the world is a witness, and I can easily imagine the revulsion that Oshima and many others felt as he saw Vietnamese citizens, his fellow Asians, slaughtered so recklessly in a war that didn’t need to be waged.

I’ll wrap up my remarks here by admitting that in my own estimation, I still have a lot to learn about what motivated Oshima to express himself on film the way he did here. I’ve only seen one other selection from this set so far, Japanese Summer: Double Suicide, which like Three Resurrected Drunkards also starred Kei Sato, who passed away last year and received this tribute on our site. Sato is a powerful presence here, even in a supporting role. But the lasting impression left on me by this particular film involves the steely nerve that Oshima displayed in making this film just the way he did, then submitting it to his studio.

Without much if any consideration for broad-based commercial appeal, Oshima still gave us a bright, colorful and adventurous excursion into territory seldom explored. Putting his heroes in drag, injecting comic violence and blatantly disjointed visual elements that emphasize the conceits of cinematic compromise, Three Resurrected Drunkards doesn’t exactly go down smoothly. But it does demonstrate a ballsy level of confidence that serves as its own kind of inspiration.

My hunch is that I’d do well to watch the earlier films in this box set in order to better understand how Oshima got to this place, but that’s not how it worked out for me. Still, I’m glad to have made my acquaintance with these Sinners in Paradise. If my comments haven’t scared you away yet, I recommend that you give it a shot yourself.

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)