Regular readers of this Journey Through the Eclipse Series may have noticed that I usually have a review ready to post every Monday afternoon right at 3 pm East Coast time, Noon on the Pacific. I wasn’t able to meet that deadline this week, partly related to holiday family obligations, but also due to the sprawling nature of this week’s selection.

When I scheduled out my reviews several weeks ago, I figured that a stretch of extended time off from work I planned to take would provide the perfect opportunity to review an epic film, just the kind of movie that one can dig into over the course of a long cold weekend. Though it’s not really a Christmas film, it is indeed one of the other “greatest stories ever told” – namely, the 1934 adaptation of Victor Hugo’s monumental novel of 19th century France, Les Misérables, from Eclipse Series 4: Raymond Bernard.

I don’t think I’m taking much risk in presuming that Les Misérables is most familiar to the majority of this column’s readers through its relatively recent incarnation as a highly successful stage musical, currently the longest running theatrical production in the world, which has been going strong since the English-language version of the show debuted back in 1985.

However, the story has been presented on celluloid many times over the past 100 years. Wikipedia lists more than 50 different live action film adaptations, along with numerous animated and radio renditions of the immortal story of the criminal Jean Valjean and his relentless pursuit by the vengeful zealot Inspector Javert. Alongside this central narrative thread, Hugo wove a vast tapestry of supporting characters, the breadth and variety of which gave him ample opportunity to comment on political, cultural and religious issues of his day.

In order to do the massive novel justice (which runs to nearly 1900 pages in its original language), the French studio Pathe-Natan enlisted the celebrated director Raymond Bernard to create not one, but three separate films, designed to be viewed on successive evenings, in order to adequately capture the full scope of the novel. Bernard was fresh off the success of Wooden Crosses, the very first film I reviewed in this series, and still one of the unrivaled triumphs among films set in World War I.

I’m far from being an expert on the cinematic history of Les Mis, but I’ll take it on trust from those who’ve looked into it that this is clearly the definitive version of the story on film. There have been other high-quality adaptations for sure, but none that rival this one in capturing the gritty authenticity and and sublime pathos that Victor Hugo imbued into his masterpiece.

So in honor of the director’s original intention, I’ll be breaking up this review of Les Misérables into three installments, one per day over the course of this week. Part One, Tempest in a Skull, focuses on the conversion of Jean Valjean from a hardened, selfish thug into a compassionate and noble humanitarian, who nevertheless remains deeply conflicted by the shadows of a past he would gladly forget, if only his conscience allowed.

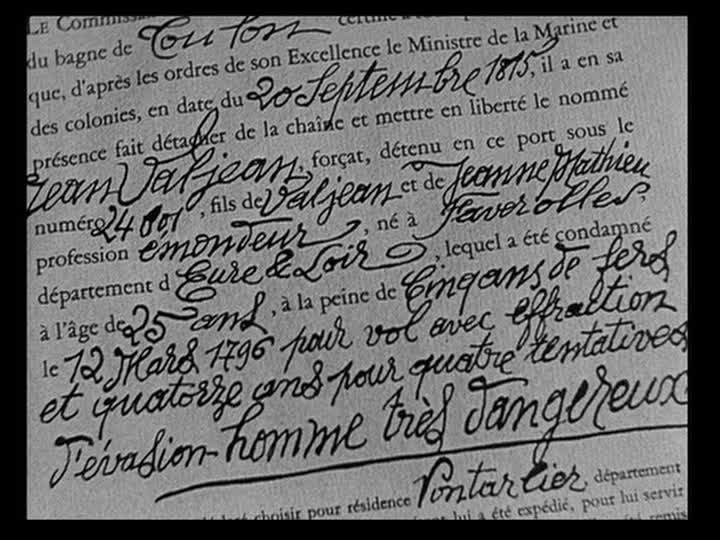

We first see Valjean at the depths of his despair, a hopeless convict who’s served 19 years of hard labor, all stemming from the simple theft of a loaf of bread that he intended to feed to his starving sister. Using his Herculean strength to prop up a marble pillar on the verge of collapsing and perhaps killing passers-by on the street, he’s granted a slightly early release from his sentence, but only on the condition that he be forever identified as homme tres dangereux – a very dangerous man. Realizing that this label is basically a continuation of his imprisonment, Valjean resigns himself to a life of crime, which leads him to steal from a merciful bishop who showed him grace and trust one dismal evening.

After Valjean is arrested for the theft, he’s stunned and deeply moved by the extension of forgiveness the bishop shows him, when his misdeeds are explained away by the bishop, resulting in Valjean’s release from arrest, and a final shot at redemption. Given the opportunity to remake himself, Valjean hits the road to seek a new start in life. Along the way, he inadvertently steals a coin from a young boy, using his large walking stick to run him off in his annoyance. Valjean has now committed the crime of armed robbery, and faces a life sentence, should he be apprehended again!

Realizing the peril to his freedom that his own deeds have created, Valjean is broken and humbled internally, and resolves as best he can to put his old life behind him. Years pass, and we soon learn that his resolution has met with success. Jean Valjean “lives” no more – he’s been reincarnated, in the same body and visage, now neatly adorned with the garb of respectability and prestige, as Monsieur Madeleine, the mayor of a French village.

Meanwhile, we’re also drawn into the drama surrounding Fantine, a pretty young seamstress who works in the jewelry workshop owned by M. Madeleine and spends her evening flirting with gentlemen in the local ballrooms. She’s a woman of one name and tarnished reputation, conceived out of wedlock and without any significant prospects in life despite her charming looks. In her naivete, she allows herself to be flirted with by a dandy, which results in an unplanned pregnancy and a hasty abandoment by the gentleman in question.

She gives birth to a daughter, Cosette, entrusting her to the care of a family, the Thénardiers, who keep her informed through letters of the girl’s condition, making sure to attach strings of financial obligation to each update in order to enrich themselves.

These scenes, among the most pathetic in the first installment of Les Misérables, definitely lend weight to the title of both film and novel, which translates into English as “The Wretched.” The general atmosphere of this film conveys the sense of anguish and psychic torment felt by most of its central characters. Fantine was originally known as the most virtuous of the grisettes who lingered around the dance hall, but she’s reduced to the lowest levels of prostitution, driven solely by her devotion to her unseen child. Valjean likewise, motivated by poverty and starvation to steal that first loaf of bread, has been terribly hardened by the torments he’s suffered ever since.

Even after achieving a degree of worldly success that never seemed remotely possible in the years of his captivity, he’s unable to fully enjoy his status, as he worries about the secret of his suppressed identity coming to the attention of his obsessed rival, Inspector Javert.

His past is at risk of exposure because of an incident in which the mayor uses his renowned strength to save a poor old man trapped under the wheels of a cart. Javert, who happened to be employed at the same prison where Valjean was held, has harbored his suspicions, and the demonstration of power just confirms them. Now the game is on, as Javert gathers evidence and keeps the mayor in his beady, resentful gaze.

If Madeleine’s ethical dilemma could only be reduced to the conflict between him and Javert, that would be relatively simple, but on top of that, he has to wrestle with the fact that another man, with whom he bears a close resemblance (and is performed by the same actor, the impressively hulking Harry Baur), has been apprehended and mistakenly identified as Valjean, and now faces a life sentence for crimes that he did not commit.

This clip captures the essence of the Tempest in a Skull referred to in the title for this installment – that voice of conscience that impinges on us all in moments of crisis, whether or not we choose to heed its urgent warnings.

The segment also gives a nice sampling of Bernard’s cinematic techniques, all canted angles and extreme lighting used to impress the high drama of these scenes upon his audience. Les Misérables is a brilliant showcase for the classic portrayal of moral conflicts involving self-sacrifice and noble resignation for the sake of principles and a clear conscience.

In an era where anti-heroes and ironic self-reflexiveness all but dominate serious (and not-so-serious) cinema, I think it’s highly worthwhile to stay in touch with old fashioned, virtuous films created in a frame of reference that is admittedly hard to capture in our postmodern culture.

Watching Mayor Madeleine voluntarily divulge his secrets in the presence of judge, jury and a multitude of witnesses, knowing that it will cost him his freedom and perhaps his very life, is quite a stirring moment. Of course, we all know that the story doesn’t end there – we still have three hours of movie left to get through! Valjean, now exposed, has some big adventures ahead of him, and Javert’s authoritative extension of “the long arm of the law” turns out to be just a temporary success.

Plus, there’s the whole matter of what happens to Fantine (hint: you won’t see her in Part II!) and her hard-pressed daughter Cosette (another hint: her role just gets bigger as we move along!) I’ll have more to say about all that tomorrow, in Les Misérables: The Thénardiers.

3 comments