Here’s the capper to my three-part review of the 1934 French classic adaptation of Les Miserables, what must surely stand based on its scale alone as the most epic work of cinema to be found in the entire Eclipse series (though I suspect Louis Malle’s Phantom India will provide substantial competition in that regard, whenever I get to it.) It’s from Eclipse Series 4: Raymond Bernard, titled Liberty, Sweet Liberty, at least when translated into English.

(Here are links to Part 1 and Part 2)

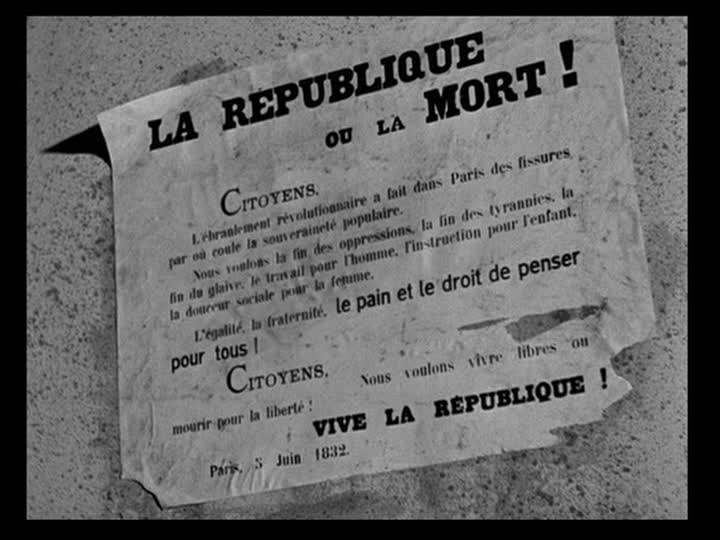

Les Mis Part 3 opens with immediate dramatic tension, as Paris is poised on the edge of chaos. Talk of revolution, fueled by rampant poverty and blatant injustice, has put both citizens and the government on alert, and now the death of a prominent general, with all the attendant military honors, has created the perfect situation to trigger a popular uprising. On the one side, the soldiers make their preparations, readying their mounts and fastening their bayonets. On the other, the conspirators issue their clandestine rallying cry – Republic or Death! – to rouse the rabble and initiate yet another French Revolution.

Caught up in all the tension are Monsieur Fauchelevant and his adopted daughter Cosette, who want nothing more than a life of peace. But the strife has ensnared them both, as Cosette worries about her beloved Marius, caught up in the fervor of the insurgency, and Fauchelevant seeks to emigrate from France and the peril he knows is still pursuing him in the form of Inspector Javert (played by Charles Vanel, who we will eventually see all smothered in oil in Clouzot’s Wages of Fear filmed some 20 years later.) For all its poignancy, the sweeping tides of history reduce them to the part of bit players as the Revolution of 1832 unfolds, with rioting in the streets leading swiftly to life-or-death standoffs as shots are fired, barricades are erected and the proverbial gauntlet is thrown down!

Meanwhile, the generals and assorted flunkies sit placidly in the comforts of their parlor, plotting out their strategies and minimizing the threat that confronts them. And Marius, for his part, demonstrates to his fellow revolutionaries that even though he’s admittedly in love with a sweet young blonde thing only age 16, he’s still ready to put his life on the line for the sake of the Republic. He and his boys pile furniture and cobblestones, loot storehouses and hijack public transit wagons in order to blockade the streets and claim power for the people. But little do they suspect that an infiltrator is in their midst – none other than Inspector Javert, who’s temporarily redirected his zeal for tracking down Jean Valjean in order to subvert the radicals and keep the authorities up to date with their latest maneuvers.

After a breathtaking display of brilliantly crafted miniature work, a reproduction of Parisian neighborhoods circa 1832, we’re ushered straight into the heart of the conflict, to the barricade at Rue Saint Merri, where the insurrection meetsthe powers that be, enforcers of the status quo regardless of how exploitive or corrupt it may be.

Little do the poor saps in uniform know that they are held in just as much contempt, and regarded as just as expendable, as the radicals they are battling at the orders of their superiors. This clip gives a glimpse of the hostilities, as we see the snitch Javert apprehended, and the courage of a child warrior, the street urchin Gavroche, whose reckless bravery epitomizes the Spirit of ’32.

Shortly after the conclusion of that scene, we witness the profound encounter between a tied-up Inspector Javert and the longstanding object of his pursuit, M. Fauchelevant, better known as Jean Valjean. It’s one of those perfectly constructed moments in cinema and/or literature, where the prey has an opportunity to exact vengeance on its hunter, but charitably declines to do so for the sake of justice and propriety.

The battle proceeds throughout the first hour and more of Liberty, Sweet Liberty, touching on themes relevant to our times such as suicide bombers and the extent to which one will go in order to tyranny and oppression on the larger scale. Jean Valjean gets further opportunities to display his heroics as he makes his way bearing the wounded Marius on his broad shoulders through the repulsive Parisian sewer system, a cinematic precursor to such incredible films as The Third Man and Kanal, before reacquainting himself with the decidedly merciless Inspector Javert once he resurfaces. But this meet-up doesn’t go exactly as one might suspect, unless you’ve seen Les Miserables in one of its many incarnations already. And even if you’ve seen other treatments of this classic story, I think you’ll find it ultimate resolution a bit unique among its peers, especially when it comes to the resolution between Javert and Valjean.

But the hostilities eventually give way to merriment and the promise of the future as the foment of revolution subsides and the happiness of a new marriage takes center stage. Marius and Cosette seal the bonds of matrimony, with the blessings of both surrogate fathers, and order is restored once again. Having seen his life’s mission through to a worthwhile conclusion, Jean Valjean takes leave of this world, leaving behind more than a fair share of goodwill and two silver candlesticks that shined a light on his path that others may now follow.

Les Misérables concludes on a note that reminds us however turbulent or tragic our individual stories may be, they are merely single threads on a much larger tapestry of life that weaves according to its own inscrutable pattern. Watching this last section of the film in a historical context is especially poignant as it deals with a populist insurrection sparked by extreme poverty and exploitation of the poor. Given the valiant but futile effort of the young revolutionaries in their quest for freedom and justice, it’s sad to think of the course that France was on at the time this film was made. 1934 saw the rise of right-wing forces in the French government as the contagion of fascism spilled over the borders of Germany and Italy. France was closer than anyone at the time suspected to a devastating political catastrophe just a few short years later, when their military was forced to surrender to Nazi invaders.

Despite the success of Les Misérables, the changing political and economic environment of 1934 also marked the end of the big budget era in French cinema. Its demise led to other creative innovations such as the smaller scale poetic realism styles perfected by Carne, Renoir and others throughout the remainder of the decade. It’s fitting then that one of France’s greatest national stories should occupy the place of a capstone of a formative era in French film-making. This is a marvelous work of art that despite its antiquity and relative obscurity deserves to be seen and kept alive by an appreciative audience.

1 comment