A couple weekends ago, as part of my ongoing Criterion Reflections blogging project, I watched Il Generale Della Rovere, a 1959 film directed by Roberto Rossellini that marked one of the commercial and critical high points of his career, yielding his biggest box office results since his breakthrough Rome Open City and major festival hardware (Venice’s Golden Lion for Best Film that year, among others.) Perfectly in keeping with his restless, artistically ambitious yet self-deprecating character, Rossellini afterwards expressed a fair amount of ambivalence toward that film, despite its indisputable success. It wasn’t too much further along into his career that the great pioneer of Neorealism, after proving that he could crank out a hit movie if he really wanted to, finally turned his back on commercial aspirations, choosing instead to produce films on his own terms that attempted to elevate the consciousness and inform the intellect of his audience, or at least those who chose to make the effort to follow wherever his vision led.

Since I enjoyed Il Generale Della Rovere, I was curious to see just what kind of new directions Rossellini had in mind for the final phase of his life’s work. To discover what he was aiming for, I turned to Eclipse Series 14: Rossellini’s History Films – Renaissance and Enlightenment, which contains three of his last productions, shot in the early 1970s. And when I saw that one of the made-for-TV programs in that box featured a musical soundtrack composed by Manuel de Sica, son of the great Vittorio de Sica who played Il Generale, that just sealed the deal. I knew I had to make a pilgrimage in time, back to The Age of the Medici.

Since I’d already watched and reviewed Cartesius, one of the other titles in this set last October, I already had some idea of what I was in for: a drily performed, historically detailed and highly literate re-enactments of pivotal episodes in the unfolding of European civilization, especially in regard to the development of the “big ideas” that shaped the modern society we now take for granted. True to the convictions of a man who could state sincerely that “cinema is dead,” Rossellini made no attempt in these films to stir our emotions or hook us in via charismatic personalities, dramatic narrative twists or any of the usual ploys that gratify the crowds. He knew, with supreme confidence, that the subjects of his study were important in their own right, with little need for manipulative embellishments. If that significance was not readily self-evident to members of his audience, he was content to let them go their own way, distracting themselves with their banal entertainments until they were capable of recognizing the value of the hefty substance he placed before them. And if that sounds haughty, arrogant, pretentious to you, then go ahead and stop reading right now. You’re just not ready to dig into Rossellini’s History films, let me be the first to tell you.

Of course, summing up the conflicts of an era as complex and multi-faceted as the emergence of what we now refer to as The Renaissance in 15th century Florence, Italy requires a large canvas, which is why Rossellini delivers this history in a video approximation of one of the favored artistic formats of that era, the triptych. The Age of the Medici is a three-part TV miniseries of sorts, each episode focusing our gaze on an important element of a larger story. Part 1, “The Exile of Cosimo,” chronicles the rise of Cosimo de Medici, head of a prominent merchant family whose uncanny business sense enlarged his fortune to the point where he was able to wield massive power, not through the authority of the church or the raw military power exercised by princes, but through the uniquely persuasive effects of cold hard cash. The series opens with Cosimo attending his father’s funeral, learning the terms of his inheritance and then swiftly setting in motion the machinations to put that money to work, advancing his influence, and in the process, all of human civilization. The Medici were forerunners of today’s ultrarich, able to bend the forces of law, politics, religion, art, culture and even science in ways that favored their ambitions and solidified their grip on power.

Of course, no would-be giant among men makes his way to the top without facing his share of formidable obstacles, and Cosimo found his adversary in Rinaldo degli Albizzi, head of the rival Florentine clan who mistrusted the Medicis’ motives and sought the means to cast them as disreputable, or even criminals, if they could only find appropriately damning evidence to back up their suspicions.

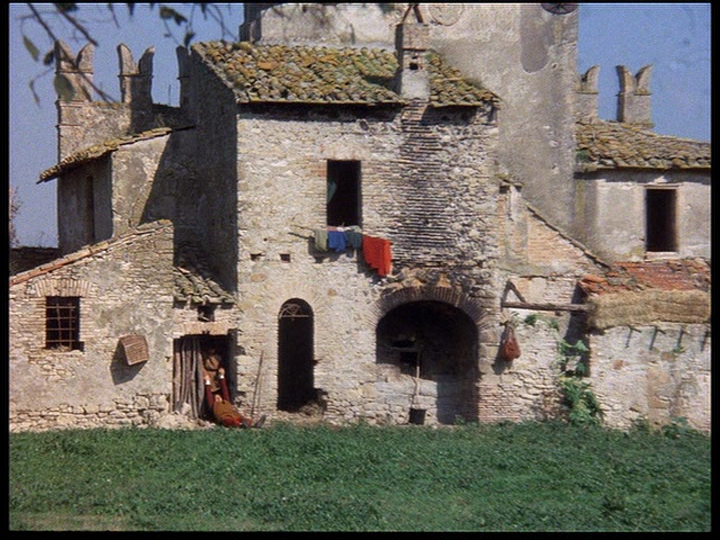

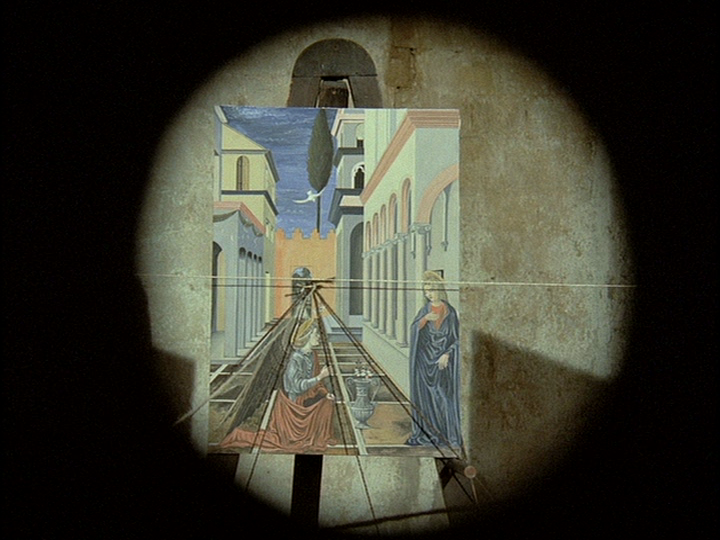

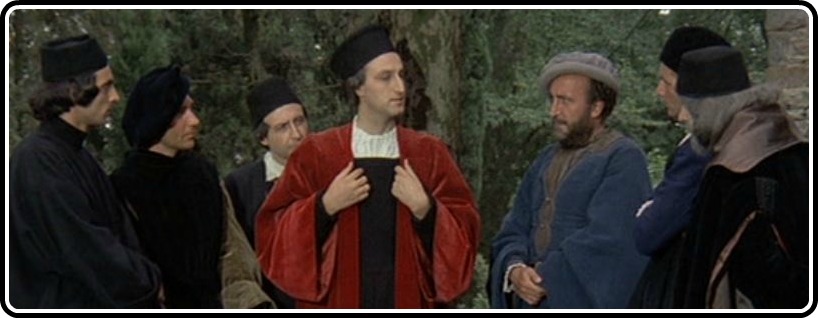

But before we get into a necessarily brief recap of the storyline, a few words are in order about the verisimilitude with which Rossellini captures the spirit of old Florence. As the screencaps show, he had to resort to some creative-but-cheap special effects that some might find cheesy but I consider admirable. Clearly working on a limited budget, Rossellini had no ability to built suitably convincing replicas of either the Florentine skyline circa 1430 or the several stages of progress achieved in Cosimo’s lifetime on the facade and dome of the Basilica Santa Maria del Fiore. So he resorted to hand-painted 2-D mockups that don’t really convince anyone, but they’re brave efforts in any case. Watching the cathedral transition from rough wooden structure to something resembling the ornate extravagance we’ve come to associate with the Renaissance over the course of four and a half hours is one of the small pleasures I enjoyed. And don’t worry, there are more than enough authentic examples of period architecture and costumery to satisfy Renaissance purists. Though Rossellini doesn’t allow his camera to revel in the scenery the way a director like Franco Zeffirelli did, I have no complaints; the settings are often quite wonderful to behold.

A main theme of the series is the slipperiness and malleability of supposedly eternal principles like law and ethics. This dialog-heavy script requires some close listening and even supplemental reading in order to pick up all the nuances it contains. The gist of it though is how increasingly sophisticated (or you could say, hypocritical) the various powers-that-be are forced to become in order to maintain the appearance of respect for ancient religious traditions (for example, the prohibitions against usury) while crafting legal loopholes such as those allowing merchants to operate pawn shops. Those who have agreed to pay a financial penalty and assume the social status of moral reprobates are signified by a red drape on their storefront, in effect given legal permission to break sacred law, reaping tidy profits for both entrepreneurs and the city fathers, and leaving matters of conscience to the individual shopkeepers to sort out for themselves.

Building on such evasive tricks so neatly woven into the emerging economic order, the stage is set to observe how Cosimo maneuvers his way through the legal, religious and political snares set before him. When his capitalistic instincts lead him to oppose a conflict between Florence and a neighboring city-state (because war is bad for business), he’s scapegoated by the Albizzis after the battle goes poorly and the Florentine forces are routed. Cosimo is summoned to appear before the Signoria, the local council of magistrates, where he faces certain arrest, imprisonment and possible execution. But Cosimo unwaveringly faces his accusers, intently pursuing a high-stakes experiment to see if his economic clout is able to produce the results he thinks it ought.

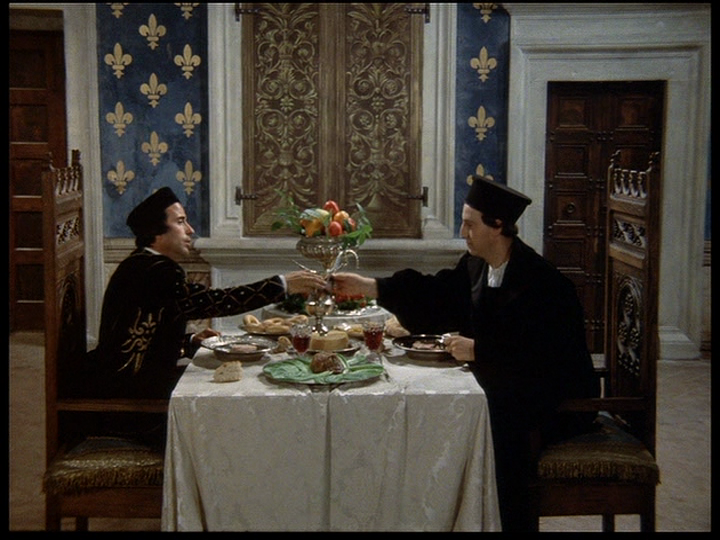

And so it turns out that, even within the confines of his lonesome prison cell, Cosimo somehow has the means to arrange for a messenger to visit his captor and drop off a gift, a simple leather bag stuffed with gold coins. And wouldn’t you know, in the very next scene, prisoner and magistrate are seated at the same table, passing knives back and forth to each other, warmly negotiating the terms of a settlement bound to disappoint those who thought they’d seen the last of Cosimo as a free and living man.

It may be worth pointing out that The Age of the Medici was broadcast in 1972, the same year that Francis Ford Coppola released The Godfather. Perhaps its no coincidence that the stories of these two prominent Italian families, known for using both legitimate and ruthless means of establishing their fortunes, both came out around the same time? There’s certainly enough of a Mafioso flavor in Cosimo’s smooth criminality to make the mental connection for many viewers, especially in the scene above, when the word vendetta is used to describe the punishment meted out on a poor soul who broke the code of honor by sharing silk-weaving secrets with others outside their ancient and notoriously secretive guild.

And just as central as economics and politics are to Rossellini’s ideas, so also art figures prominently in the story of the emerging Medici dynasty. Episode 2, “The Power of Cosimo,” depicts his return from exile in Venice, more coldly calculating and relentlessly ambitious after a few years spent plotting his ever-so-respectably applied revenge. Though Cosimo’s not beyond enforcing compliance through the administration of pain, he’d much rather get his point across building sublime monuments and establishing himself as a prominent patron of the arts. And what a time to be in that business, as the Italian Renaissance was about to burst into full bloom. Massacio’s “Expulsion from Eden” and Donatello’s statue of King David are just two of the famous masterpieces put into historical context, enabling us to see the works as something beyond merely fancy ornaments as they’re often regarded nowadays. The locals respond to them with indignation and confusion, unsettled by innovative, sensual details that call older traditions into question. We’re reminded that progress in the visual arts is not simply an exploration of aesthetic vanities, then or now. Each breakthrough, each shifting perspective in the portrayal of the human figure, carries with it larger implications about how we regard and value life, and how we understand our place in the cosmos.

But before we lose ourselves entirely in ponderous highbrow musings, Rossellini injects moments of visceral brutality to keep our feet firmly planted on the ground. Art, architecture, philosophy and religion may all seek in their own way to inspire heavenly meditations, but there’s still a dark, dirty, competitive world we each live in that has to be reckoned with as well.

Episode 3 shifts the focus away from Cosimo (though he still plays an important part) and on to another important Renaissance figure, “Leon Battista Alberti: Humanist.” This final installment is the most philosophically dense of the three, and one that I recommend to anyone who’s looking for a well-rounded overview of the mindset of that era. Here Rossellini really indulges his appetite for extended rhetorical exchanges, with characters routinely tossing out profundities and speculations that are worth pausing the DVD to ponder a bit before proceeding on to the next priceless nugget of insight. Of course, some of the philosophical musings that so preoccupied these men (and this is, for sure, a man’s world on screen; women are almost entirely silent during the scarce moments when they even appear) may not be so relevant for many viewers, but for those whose taste in movies runs toward the cerebral and analytical, I think there’s a lot to chew on here, and it makes these discs very rewatchable if you’re into that sort of thing. Here’s a sampler if you want to have a taste. There’s even a sly bit about the first “motion pictures” around the 6:30 mark!

One thing I will add here is that even though the default setting for the DVDs is Italian, there’s absolutely no reason why an English-speaking viewer should watch it with subtitles instead of the dubbed English audio track, unless you just enjoy the sound of people speaking the language native to that setting. The program was originally filmed in English, in the hopes that it could be sold to a forerunner of today’s PBS TV network. That plan fell through, so they dubbed an Italian language track over the top, and then re-dubbed an English track later on when it eventually was picked up for American distribution. The net effect is that the English dub actually syncs better with the actors’ mouths than the Italian does. The subtitles really only help if you need them to follow the progression of the dialog. I just recommend paying close attention. These are movies that actually play quite well on a computer screen, by the way, and yes, they’re available on Hulu Plus!

So yeah, these late Rossellini’s are definitely not among the thrillingest, sexiest, awesomest offerings to be found in the Eclipse Series, there’s no arguing that. But they do serve as important and unique specimens of what film can accomplish and preserve for the sake of a small but appreciative audience. Maybe even more significantly, they represent a lost utopian possibility for what one visionary director hoped the medium of television could become. Rossellini’s desire to provide solid, historically informed visualizations of defining moments in our cultural heritage, without either the dumbing down or the hyping up of conventional potboiler gimmicks usually deemed necessary to win a mass audience, hasn’t shown itself to be all that commercially viable. It’s even fair to conjecture that if Rossellini himself hadn’t established his reputation so profoundly in the 1940s and 50s, films like those he made in the late 60s and 70s might not even be revisited today. Still, watching The Age of the Medici makes me mourn just a bit for the wasted potential of commercial cable TV and what an entity like the History Channel might have become, if had we more directors of Rossellini’s singular integrity and intelligence working behind the cameras.

Mr Blakeslee, Thank you so much for taking the time to create these wonderful “program notes” to this terrific series on the Medicis. I just finished watching it and was really moved by its seriousness of purpose, its educational thrust and its beautiful re-inactment of the 15th century in Italy. Your notes help fill in the gaps in comprehension of this first-time viewer. I will certainly watch it again soon, especially the third part.