Although I have no real authority or statistical proof to back me up, I’ll start off this review with an assertion that the right of interracial couples to marry each other in the late 1950s and early 1960s was in roughly the same place in popular opinion as how the issue of same-sex marriage is viewed in Europe and North America today. Which is to say that while there remain pockets of entrenched, indignant resistance to the idea on both continents, mostly on religious or traditional grounds, over time most people’s views grow more accepting and sympathetic toward those who happen to fall in love with a partner that doesn’t fit conventional notions of who a particular person “ought” to marry, should that level of commitment develop within the relationship. My sense is that even in the past few years, it’s not just been President Obama whose opinions have evolved – a lot of people have given the matter more prolonged consideration and now recognize that there’s no sound legal or moral reason to deny these couples the ability to openly endorse and express their love for each other, with all the rights and privileges that society normally bestows on married partners.

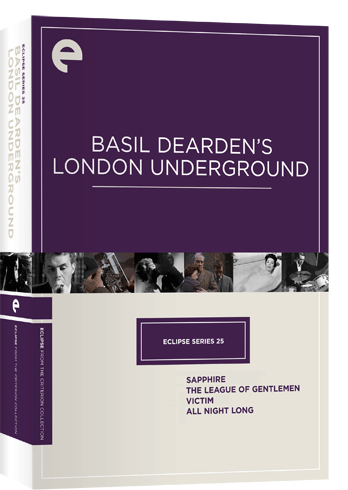

A similar progression, from attitudes of shock and surprise to matter-of-fact acceptance, over the course of a few years can be detected in how interracial coupling was portrayed in 1959’s Sapphire and 1962’s All Night Long. Both films issued from the same director and are part of Eclipse Series 25, Basil Dearden’s London Underground, the earliest and latest titles in that set, respectively. In the former, the initial appearance on-screen by the brother of a young female murder victim (whom we assume to be white, based on her brief appearance in the opening credits) is framed to stun the audience when we discover that he is, in fact, a black man of Nigerian descent. The rest of that film’s plot unfolds in response to the guilt and anxiety felt by David Harris, the white man who Sapphire was dating before she was killed. Harris endures rejection by his family and struggles to manage his own revulsion and denial. Even more disturbing, the underlying assumption that comes through the film is that his reaction, and similar bigotry from those around him, is rather understandable, even though it’s not exactly endorsed or defended as such. As one of the very first British films to even acknowledge the growing racial and ethnic diversity of post-colonial England, Sapphire marked a brave advance for its times, challenging its contemporary audience as it reflected common prejudices, even though it now comes across as a bit timid or even exploitative of the racist subtext behind the narrative.

Contrast that with All Night Long, released just a few years later, where once again, a mixed race relationship is placed at the center of the drama. This time, the focus is on a married couple: a black man and a white woman who happen to be famous performing artists within the jazz scene of that time. Unlike Sapphire‘s presumed awkwardness and discomfort over the fact that a white man would unknowingly become involved with a biracial woman, in All Night Long there’s no overt tension associated with the differences in skin color.

A few early exchanges where characters make slight insinuations about the cultural taboos challenged by the couple swiftly conclude with brief, matter of fact dismissals, putting to rest any further need to ponder the matter. Though there’s a world of difference between the mundane working class milieu explored by Sapphire and the more cosmopolitan and talent-fueled social scene of All Night Long, Basil Dearden’s indifference toward pontificating on the mixed-race theme indicates a subtle but tangible shift in attitudes, a movement in the right direction as more people realize the extent to which they’d come under the influence of needlessly destructive prejudice and modified their views. Hollywood still required a decade or more of catching up with the Brits before such relationships could be portrayed without the obligatory liberal sermonette or enlisting of Sidney Poitier to make the case, or both.

Aside from its function as a bebop-styled adaptation of Shakespeare’s Othello, All Night Long is best known and most celebrated for its musical components. Chief among them are appearances by jazz heavyweights like Charles Mingus, who’s the first player to show up for the gig, contemplatively puffing his pipe and plucking the strings on his bass before accepting the first of several tumblers of Johnnie Walker’s good stuff that will fuel his playing throughout whatever the evening has in store. Once the band begins to fill out with a few more accompanists, the music begins in earnest and hardly lets up for the rest of the movie. You don’t have to be a big jazz fan to appreciate the swingin’ vibe – my interest in the genre is generally limited to background music on warm evenings, but I found myself easily drawn in by the smooth sounds wafting through the loft.

Back to that reworking of Shakespeare’s tragedy of manipulation, betrayal and all-consuming jealousy… In All Night Long, the “Othello” part belongs to Aurelius Rex and “Desdemona” is his wife, Delia Lane. He’s a piano player and band leader, she’s a popular vocalist who retired a year prior to the story’s action after she married Rex. As the film’s title implies, the events take place over the course of one evening, a combination first anniversary party and impromptu jam session held in a stylishly appointed London warehouse on the south bank of the Thames River. The bachelor pad is located in the industrial district so that the musicians can wail with abandon deep into the night without disturbing the neighbors. Far from being the grungy loft that might first come to mind, these digs come with comfortable modern furniture, a well-stocked bar flowing with the finest champagne and Scotch whiskey, all paid for by millionaire Rod Hamilton (played by Dearden mainstay Richard Attenborough) for the amusement of himself and dozens of his closest friends and hangers-on.

The anniversary party comes as a total surprise to Rex, who would have been content to spend a quiet night at home with his lovely young wife, but Delia was cleverly drawn into planning the event. On her end, the get-together is just a fun way to celebrate the special occasion, but others involved in putting on the bash have ulterior motives – namely, drawing Delia out of her self-imposed withdrawal from the music biz and turning her into a stepping stone to further their own ambitions. Delia’s decision to step out of the performing spotlight was done for the sake of Rex, who’s afflicted with a possessiveness borne from insecurity that he might someday fall out of his wife’s favor and lose her to another man. It’s a choice she struggles with, but willingly sticks to because she loves her man.

A trio of gents have a vested interest in luring Delia out of retirement. Lou Berger, the top booking agent for jazz acts in England, sees obvious profits to be made from having her as a touring headliner, while Hamilton, the impresario who bankrolled the shindig lavishly enough to lure talent like Dave Brubeck (pictured above) to stop by and lively up the place, would get a real kick out of knowing that his fun money played in a big part in persuading Delia to grace the spotlight once again. But the real driving force behind all the plotting and maneuvering is our story’s “Iago,” drummer Johnny Cousin, a chronic misanthrope who’s convinced himself that the key to his success and eventual contentment rests on starting his own band, where he can be the headliner, not an anonymous session man sitting back on the dark part of the stage.

Cousin’s big problem is that, even though he’s been pitching the idea to Delia of joining his band for quite a while now, and even persuaded her to do some preparatory rehearsals, he can’t get her to commit to the project. And without her commitment, he doesn’t stand a chance of getting the financial or booking support he needs to become a legitimate frontman. But Delia’s refusal is just a temporary obstacle, as far as his overbearing pretension is concerned. With all the key players required to advance his scheme gathered in one room for the night, Johnny recognizes his opportunity and lights upon a solution. (And that’s not all he lights upon – he’s holding a cannabis cigarette in that shot, another surprising counter-cultural bit tossed so casually into the mix.)

Cousin’s plan involves provoking jealousy and confusion between Delia, Rex and Rex’s weak-minded band manager Cass, an old friend who first introduced the couple to each other and for whom Delia still feels a strong affection. Cass is a recovering hop-head himself, who’s easily manipulated by the villainous drummer into relapse and winds up letting his inner demons do too much talking for him once he’s under the influence.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2os0-SxiKxA&version=3&hl=en_US&rel=0]

The clip above, which begins just as Cousin takes his last drag off a “funny one,” gives a great example of the sharp skill with which Dearden blends the jazzy ambience, the manipulative psychodynamics initiated by Cousin and the underlying insecurities that corrode Rex’s bond with his wife. It features a solo by noted alto sax player John Dankworth.

If you haven’t picked up on it yet, the Johnny Cousin/”Iago” role is performed by Patrick McGoohan, a few years before he established himself most famously as The Prisoner, a remarkable cult-TV classic that ran for a season in 1967-68. From an acting perspective, McGoohan totally steals the show, infusing the unfiltered malevolence and ruthless selfishness required to generate both hatred and a peculiar fascination from the audience. Over the course of one night, he proves himself to be a total creep, dissing his wife, betraying his supposed friends and ultimately destroying whatever slim prospects he might have had to put his name at the top of the bill. He even throws in a pair of thunderous drum solos en route to his self-appointed oblivion, including one to close out the evening as All Night Long draws to its partly bitter, partly redemptive conclusion.

Even though Othello is one of my least favorite among Shakespeare’s great plays (I just agonize over the sadness of seeing true love between mature adults so wastefully spoiled and thwarted, much more than Romeo and Juliet, who are after all just a couple of dumb impulsive children who get in way over their head, albeit with tragic results), I was positively impressed with Basil Dearden’s shrewd adaptation, incorporating some of the story’s strongest elements while taking liberties with others. All Night Long makes for a strong nightcap to close out one of the Eclipse Series’ most diverse and entertaining sets, especially for those who don’t enjoy reading subtitles in order to understand what’s going on. Each of the films provide a revealing glimpse of English culture in a state of transition at the beginning of a decade that still wields such a heavy influence on the debates and discussions going on in our world today.

![Bergman Island (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/bergman-island-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![This Is Not a Burial, It’s a Resurrection (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/this-is-not-a-burial-its-a-resurrection-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![Lars von Trier's Europe Trilogy (The Criterion Collection) [The Element of Crime/Epidemic/Europa] [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/lars-von-triers-europe-trilogy-the-criterion-collection-the-element-of-400x496.jpg)

![Imitation of Life (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/imitation-of-life-the-criterion-collection-blu-ray-400x496.jpg)

![The Adventures of Baron Munchausen (The Criterion Collection) [4K UHD]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/the-adventures-of-baron-munchausen-the-criterion-collection-4k-uhd-400x496.jpg)

![Cooley High [Criterion Collection] [Blu-ray] [1975]](https://criterioncast.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/cooley-high-criterion-collection-blu-ray-1975-400x496.jpg)