Family, job and taxes, that inevitable trio of obligations looming large over most of our lives, intruded severely enough on my leisure last week that I simply didn’t have the time to crank out another one of these Eclipse reviews. But I’m back at it now, and happy to have the opportunity to share with you my growing appreciation for what I think must be the most undeservingly under-recognized director in that entire line of DVDs. Hiroshi Shimizu, a contemporary peer of such luminaries as Ozu, Mizoguchi and Naruse among Japanese film directors, out-produced them all in sheer quantity over the course of his career, helming over 160 titles between the 1920s and 1960s. Maybe that prolific output worked against him, maybe the quality of his efforts declined seriously over the decades. I really don’t know, and it would take a lot of effort on my part to find out, since his films are so difficult to find here in the States.

A couple years ago, Criterion did their small part in trying to rectify the situation by releasing Eclipse Series 15: Travels with Hiroshi Shimizu, a box of four films from the 1930s. They provide a fascinating and priceless view of pre-war Japan, especially because Shimizu enjoyed taking his camera on the road, using real-life locations as the setting for his stories instead the usual studio-bound environments that the early days of sound-equipped cinema typically required. This week, I’m focusing on 1938’s The Masseurs and a Woman.

There are a few reasons I could cite for why I chose this particular title. The last time I took a break from this column, I returned with a Shimizu review (Mr. Thank You). Also, a Japanese film from this era fits in pretty well with two recent entries in the series, Ozu’s I Was Born, But.., and Naruse’s Flunky, Work Hard. (In fact, now that I mention it, I think I’ll go ahead and complete the cycle with a review of one of Mizoguchi’s 1930s Eclipse DVDs in next week’s installment!) But the actual reason this film seemed primed to take its turn in my survey is that Hiroshima mon amour, the 1959 breakthrough film by Alain Resnais, is coming up next on my Criterion Reflections blog, and the famous opening sequence, of limbs entwined and hands grappling bare flesh, brought to mind the idea of massage. The “Hiroshi” connection between the two is just a mere coincidence.

But enough of that prattling. I’m sure by now you want to know what I have to say about the film itself. The Masseurs and a Woman is an exercise in indirectness, a subtle, slow-paced story in which characters come together in ways that suggest predictable outcomes and story arcs, only to diverge from what we’d normally expect to happen in similar set-ups from more conventional directors. What starts out as a character-driven comedy quietly tilts to a romance, then to a mystery, then to a sad melodrama, without ever taking the full plunge into any of those genres. Shimizu demonstrates an easy capability to wrestle those emotions from his viewers, if he so chooses, but he has other objectives in mind it seems, namely a desire to capture the uneasiness and ephemerality that occurs so often in human relationships. Our vulnerability to getting hooked into emotional connections that we know are fragile, won’t last and probably lead more toward frustration and disappointment than to lasting satisfaction, lurks as the background context of this seemingly simple story.

The masseurs, Toku and Fuku, and the woman, who’s never named in the film but is credited as Michiho, are among a group of people who come together by happenstance at a mountain resort in the springtime. The masseurs happen to be blind, and it seems like that was an occupation typically filled by men suffering that disability, as a way to spare their customers the potential embarrassment of visible nakedness while receiving their rubdown. Toku, Fuku and Michiho all arrive at the spa simultaneously, and Toku, who first detected Michiho’s alluring scent as she passed them on the road riding in the back of a carriage, quickly falls into an infatuation with this alluring, available, unaccompanied woman. This clip, from the opening minutes of The Masseurs and a Woman, gives a good impression of Shimizu’s patient, meandering style as we first meet our protagonists. You’ll see that the blind men have a bit of a chip on their shoulder, and who can blame them, living as they do in an era where little by way of reasonable accommodations are made for their handicap. Indeed, the film as a whole makes their blindness the butt of many jokes that will strike some viewers as harsh or insensitive. But such were the times…

She is indeed a beauty, and no one would fault a young single guy for daydreaming about getting intimately involved with her, but come on now. He’s a blind masseur, probably destined to spend his life on the lower rungs of the social ladder. She’s an attractive head-turner, easily capable of winning the affections of men much more prosperous and significant than Toku. But as we know, such rational considerations often fail to persuade us once our hearts become fixated on an object of desire.

And just about the time that the audience recognizes that we’re being led down a path focusing on Toku’s naive romantic folly, falling for a woman clearly beyond his reach (regardless of how much passion and skill he might invest in her massage), a plausible rival emerges. A fellow traveler, accompanied by his bratty nephew, begins his own flirtations with lovely Michiho and the stage is set for a love triangle to develop, with the pesky kid on hand to complicate things right on cue. Shimizu leads us along for a bit, before shifting gears once again as a dilemma involving the mysterious theft of money from guests at the inn takes center stage, with evidence pointing accusingly at the enigmatic Michiho, which in turn stirs up troubling thoughts and a turmoil of conscience on the part of her foremost admirer Toku.

Any further recap of the plot does a disservice both to Shimizu and his largely untapped audience, who all deserve the novelty of a first, unspoiled acquaintance at this stage of the relationship. This is story-telling of a sort that rarely finds studio funding these days; in fact, I shudder to think of the crass exploitation that Hollywood would heap upon this scenario. Two wise-cracking blind guys, a hot mysterious single chick on the run, a traveling salesman, stolen cash, all at a remote mountain resort health spa with lots of free time on their hands… well, the ingredients are all in place for a run-of-the-mill trivial vulgar comedy, not to mention a porn flick.

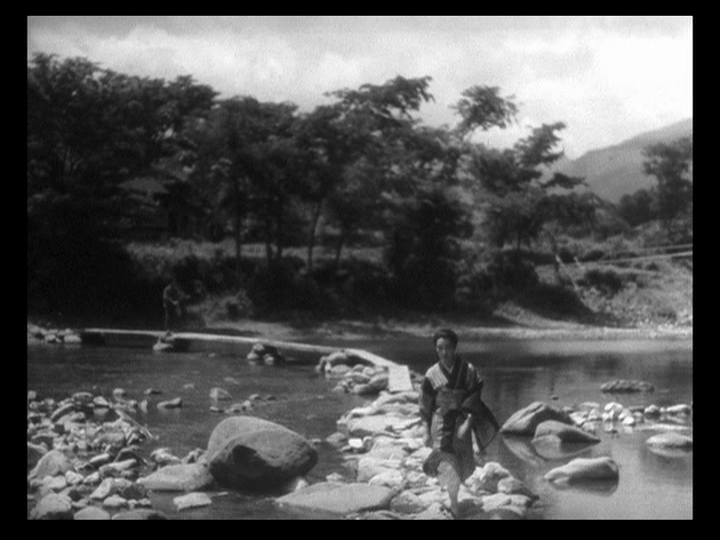

For better or worse though, The Masseurs and a Woman is from 1930s Japan, not 2010s USA, so we’re spared the commercializing pressures that are too often placed on today’s films and instead get to savor some exquisitely simple moments, such as we find in the tranquil postcard-worthy shots above, or in this remarkable, impressionistic clip below, in which Toku responds just a bit too eagerly to Michiho’s request for him to give another massage, but finds himself being toyed with and taken advantage of because of his blindness.

The sensitivity with which Shimizu composes the scene, allowing the head movements and facial expressions of the actor to convey a depth of yearning and disappointment as the woman he knows is nearby recedes gradually out of focus, is indicative of the director’s confidence in his own handling of the material and the viewer’s ability to intuitively comprehend such cinematic moments without the need for spoon-feeding exposition.

Clocking in at just over an hour, The Masseurs and a Woman holds up well to multiple viewings, even after the bittersweet twist of an ending is familiar and expected. Whether it’s to simply take in the rustic beauty of old Japan and the charming customs of life in a country spa, or to enjoy the curious gliding effect of Shimizu’s interior tracking shots, a leisurely hike with Toku, Fuku, Michiho and crew may be just what the doctor ordered to invigorate our spirits and provide a fresh perspective on the ups and downs of life.

3 comments