As most readers of this site have probably heard by now, the late and great Swedish director Ingmar Bergman unexpectedly stirred up chatter on the web when doubts were cast on the circumstances of his birth. Recently released DNA tests apparently show that he was given birth by Hedvig Sjöberg, a different woman than the mother who raised him, Karin Bergman, about whom her son Ingmar has written extensively and who served as a major source of inspiration for the films he made over the course of a lifetime. This article is the most extensive (and presumably fact-based) summary of the controversy, and my purpose here is not to engage in any extended speculation or gossip about what the allegations mean or how it changes our assessment of Bergman’s work.

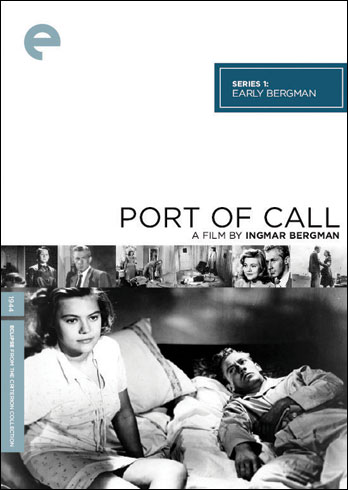

But given the significance of Bergman’s childhood and family life as it directly informed some of his most important films, I know the community of Bergman scholars will be energized by these new developments and I do look forward to reading more about these matters from people much better informed than I am on the intimate details of his life and career. The news itself was enough to steer me toward another one of the Eclipse Series 1: Early Bergman films for this week’s column, and I’ve chosen Port of Call, a 1948 release that the director acknowledged was “made in the spirit of Rossellini.” Since I’ve been on a bit of a Rossellini kick myself lately, it fits the bill quite nicely!

Bergman’s fifth directorial effort on celluloid (in addition to his prolific theatrical output at this time), Port of Call is regarded as the first emergence of his technical mastery of film, as well as an indication of his willingness to address provocative topics in a straightforward manner. Even though the overall craftsmanship represents advancement compared to Crisis, his debut feature, it’s clear that Bergman is still working as an industry director, following the stylistic trends of his day and years away from refining the distinctive auteurist look and feel of later productions in which he himself became a worldwide trend-setter.

Port of Call is not what anyone would consider an early masterpiece of Bergman’s, but it does offer a unique opportunity to see him work with characters and exteriors quite different than what we’d see from him over the decades to come. His statement of homage to Rossellini (in his War Trilogy phase) is appropriate here, as the action takes place in a gritty industrial milieu, the Swedish harbor town of Gothenberg, again a more blue-collar and rougher edged environment than the affluent bourgeois settings of his later contemporary dramas.

The story has familiar elements to many a melodramatic potboiler. As the film opens we see Berit, a young woman driven by suicidal impulses for reasons as yet unknown to us. She starkly paces to the edge of the seawall, pauses a moment, then steps forward into open air. Quickly rescued and pulled, kicking and screaming, into an ambulance, she first crosses paths with Gösta, a sailor just coming ashore for a leave and a time to sort out his options; he’s uncertain about his future, but has no reason to think the flailing mess of a girl in front of him will play any part in it.

But this is the movies, and these early chance encounters are placed before us for a reason, are they not? Berit’s sad and frustrating life becomes the subject of our examination, and Gösta’s random entry into her story presents itself as a possible key to shaking up the equilibrium and pulling Brita out of her downward trajectory… if he’s able to avoid being pulled into the undertow himself.

But let’s revisit a little bit of that Rossellinian Neorealist flavor before plunging any deeper into the story at hand. The images above and below provide a sense of the atmospherics that make this film distinctive within the Bergman canon. The cameras fix upon the drudgery and grime of the everyday lives of working men and women, and not merely in brief snippets either. The scenes are given ample time to allow a viewer to have a sense of the monotonous physicality of the labor and to contemplate its soul-deadening effects.

Given its salty, oceanside setting and the similarities of their titles (at least as they’re translated into English), Port of Call also reminded me of Marcel Carne’s great 1938 classic, Port of Shadows, one of the crown jewels of French Poetic Realism, a subgenre that prefigured film noir and Neorealism itself, basing its stories on world-weary individuals who’ve hit the skids, defy the odds and almost inevitably wind up either subject to bitter heartbreak, or dead, or both. More self-consciously arty and stylized than Neorealism, which put more emphasis on the “real” in its pursuit of non-studio settings and a more pragmatic political agenda, Poetic Realism had gone out of vogue after the war, but it seems likely to me that Port of Shadows still exerted an influence on Bergman’s shipyard industrial scenes.

Back to Berit and Gösta then… their next encounter is a few nights later, after her demons have subsided a bit and one of his working buddies has convinced him to put the book down and head out on a Saturday night for a bit of fun and unwinding at the local music hall. Uncomfortable delivering his pickup lines, Gösta fumbles around a bit before he sees Berit tearing it up on the dance floor and figures she might be a little more approachable. She is, and they click.

Soon enough, they make their way back to her apartment, where Father is out to sea and Mother is visiting a relative. The connection is made, not without some awkward moments and emotional complications, but there’s enough going on between them to encourage the pursuit of more. Still, uncertainty hangs heavily over the relationship… what will Gösta think of Berit when or if he learns about her past? How much can Berit really expect from a sailor who’s on leave, close to broke and with no real reason to stick around?

They get to enjoy some time out on the town, briefly distracting themselves at the movies while Berit does her best to dodge the louts and big mouths they pass on the street who might say more about her personal life than she’s quite ready to disclose to her new beau. I always enjoy movies scenes like this that give a glimpse of what going to the cinema was like many decades ago.

Gösta and Berit quickly discover enough substance and passion in each other to begin believing that something real and lasting is in development between them. But that turns out to be the easy part; it gets a lot more complicated as the privacy of their relationship is exposed to more public scrutiny. The workingmen do their part to fill Gösta in on what kind of a tramp he’s gotten himself involved with…

… while Berit has to endure relentless shame and humiliation poured on her by her mother, who correctly surmises that there’s more going on between her daughter and this new transient stranger than her sense of decency can allow. These scenes of strong-willed women in intractable conflict offer probably the strongest link between Port of Call and Bergman’s future work that also built on such dramatic exchanges. The camera work, using mirrors and some nimble dolly shots to capture the psychic battle, adds interest. This film was the first collaboration between Bergman and cinematographer Gunnar Fischer, who played a crucial role in establishing the director as a living legend by the late 1950s in films like The Seventh Seal, Smiles of a Summer Night, The Magician and Wild Strawberries.

A big part of Berit’s past that she’s anxious to conceal, until the situation is right at least, is the time she spent in a girl’s reformatory, sent there due to her acting out behavior that was triggered by the abusive home environment she grew up in. Then as now, of course, it always seems to be the children who pay the heavy price while the adults who screwed things up get off scot-free. Bergman offers up a flashback scene to put Berit’s troubled history before us, delivering with it some pointed commentary on the corrosive effects that well-intentioned adult “guidance” can have when the youth they’re trying to help aren’t given a voice or adequate respect. Though I’m reluctant to level any kind of a charge resembling “exploitation” at such a venerable and serious artist as Ingmar Bergman, it’s hard to refute the impression that he was at least willing to offer up a bit of the risque to promote interest in his films.

One scene that Bergman later expressed his regrets at including in the final cut of Port of Call is a brief falling out that Gösta has with Berit, where he seeks the consolations of a hooker and a bottle of booze. He winds up drunk and raging, going so far as to smash his whiskey bottle on the bed post and trash his room – Bergman at his pulpiest! He later went on to say that the scene was a big mistake, “out of tune with the rest of the film.” It seems that he was trying to add some notes of strife and action, building on a back alley brawl scene from earlier in the film that again struck me as well outside what I’ve come to expect from an Ingmar Bergman movie. I feature these shots just because I like the composition and it’s always interesting to note what great artists consider to be among their major blunders.

Port of Call‘s final third introduces another burst of scandal as one of Berit’s friends from the reformatory finds herself pregnant and resorts to having a black market abortion. Post-procedural complications ensue, stoking further conflict and tensions between Berit, her mother, the legal authorities and Gösta. Throughout it all, Bergman levels his share of political and cultural critiques, though they’re not delivered with the kind of breathtaking finesse and devastating emotional impact that would win him lasting fame in later works. Here Bergman is just stepping forward from his apprentice phase, and this film is really best reserved for the appreciation of those who want to dig deeper into the director’s formative years.

The ending, a somewhat forced conclusion that seeks to offer an optimistic outlook on the future, is commonly criticized, and it’s an easy one to pile on, but I don’t see the point of that. It would be just as conventional and predictable to have had either Berit or Gösta die or be otherwise be cut off from the other. I think Bergman was again trying to honor that ambivalent opening of possibility we see at the end of the early Neorealist classics like Bicycle Thieves (read James’ recent review of the non-Criterion blu-ray release here!) where it’s not exactly a happy ending – plenty of uncertainty still hovers over our protagonists, but they’re not giving up altogether. His inability to squarely hit that mark shows just how skilled the Rossellinis and de Sicas of that time really were in delivering their cargo. Bergman was still learning how to drop the freight for maximum payoff, but we all know that he got it right eventually.

Nice piece Dave. I gotta pick up this set. Looking forward to hearing your thoughts on Shadows over at Criterion Reflections.

Most interesting to read about Bergman trying his hand at a different area than the entertaining period pieces and intense dramas he’d make his name on. I’ve been on a bit of a Bergman kick myself these days – expecting to get Smiles of a Summer Night in the mail any day now! But I digress – good work as always, David!

I don’t mean to discourage you from picking up that set Kyle, but the Early Bergman films are also available on Hulu Plus, so you might want to give them a look on that site if you’re a subscriber. Another important Bergman film that hasn’t had a Criterion or Eclipse release just showed up on HP as well: Summer With Monika starring Harriet Andersson. If you remember the scene in 400 Blows where Antoine and his friend swipe a pin-up picture of a pretty young woman off a wall during their epic hooky adventure – that’s her! :)

You’re in for a treat with that Smiles blu-ray. I haven’t gotten mine yet, but I will eventually – have a few other new releases to get before I double-dip. But that’s a really wonderful, funny film and I just gotta say, Eva Dahlbeck in HD is easily worth the price of purchase!

Actually, I got the non-HD disc – I pounced on a used copy sold off by someone who probably double-dipped for the Blu! The image quality is still pretty great, though – I’m content!

The film certainly gathers an appealing assortment of ladies – Dahlbeck, Ulla Jacobsson, Margit Carlqvist. For me, though, it’s all about Harriet Andersson – what a dish! It’d indeed be great if Criterion handled a release of Summer with Monika.

Fair enough, a great deal on a used DVD makes up for the lack of HD, and the women (and the rest of the cast) are wonderful enough to shine through in the old format. I agree re: Summer With Monika, it would be great to see it receive a proper CC release on DVD/Blu-ray, but I’m glad that they’re streaming it now at least. Maybe if enough of us watch it online we can generate momentum for Criterion to fill this significant gap in Bergman’s filmography. Then they can work on better editions of Persona and his mid-to-late 60s stuff sooner rather than later!

david – thanks for the in depth review of a hidden treasure. I would expect nothing less in your very capable hands.

david – thanks for your in depth review of this hidden treasure. you never here about this and most of the releases that make up the eclipse series. in your very capable hands we get more than opinion. we get the the substance, sustenance,

back story, and any creative parameters framing the production as it happened. I picked up the Raymond Bernard and Oshima’s Outlaw Sixties because of your involvement. keep up the excellent work – russell scott

Thanks Russell, that’s very nice to read, I appreciate your comments! I definitely enjoy digging a little deeper into these Eclipse films than the usual capsule reviews and I’m glad to share my discoveries with others who are at least curious about what those DVD boxes contain. I’ve been at this column for just over a year now, still have a long way to go but I expect it will be a fun journey for any and all who want to share the trip with me!