For various and sundry reasons, this past week took a heavy emotional toll on me, as I dealt with some sad news affecting my family and contemplated assorted troubles in this world. Some of them affect me more directly, others just overlaid a pall of regret at how difficult life can be for so many people. And even though I have to acknowledge it as a superior masterpiece of brilliant cinematic art, the accompanying task of watching Ingmar Bergman’s Through a Glass Darkly for my Criterion Reflections blog sure didn’t help much to alleviate the ponderous mood that settled in and overtook me. Finishing up that latest review just in time for what proved to be a busy weekend full of Easter and family festivities, I scoured through my Eclipse Series collection to find an appropriate follow-up and settled on another Bergman offering. It had a promising title – To Joy – and featured the music of Beethoven. Shot roughly a decade before he made Through a Glass Darkly, just before the upcoming Criterion releases Summer Interlude and Summer With Monika, I took a chance that To Joy, from Eclipse Series 1: Early Bergman, might be one of the auteur’s lighter offerings.

So… was I shocked, disappointed or depressed to learn within the first few minutes that the story of To Joy is told as a flashback of a husband just learning that his wife had been killed by an exploding kerosene stove? No, no and no, actually. Despite the morbid misery of its underlying theme, I inherently trust Ingmar Bergman to make these grim explorations through the starker landscapes of the human condition as aesthetically pleasing and intellectually illuminating as I could ever desire. And once again, his earlier formative works lived up to the expectations that his later, greater films went on to create.

After seeing the poor graphic design that resulted in nearly unreadable title and credits, I can easily understand why Bergman eventually chose to open his films with simple white lettering on a pitch black background.

As the intertitle above indicates, To Joy is the story of a marriage, now concluded by tragedy but not all that strong or resilient in any case throughout the course of its seven or eight years duration. A cursory comparison of its events, placed next to a chronology of Ingmar Bergman’s personal life, offers ample hints that the two narratives run in close parallel to each other: two young lovers, each with their own turbulent pasts and present emotional volatility, draw together almost in direct defiance of their own best judgment as they each see the threat posed by their underlying incompatibilities. She’s insecure, needy, bottles up her feelings and keeps secrets that blow up when they finally come out into the light of day. He’s selfish, rude, arrogant, consumed by his own pride and vanity, and ultimately unable to resist his own adulterous urges – basically, a real shit heel, as Bergman’s men often prove to be, especially in comparison to the fortitude and intelligence displayed by his female characters, and especially when we examine those male characters who serve as proxies for Bergman himself.

And if those hints are explicit enough, he spells it out plainly in one of his autobiographies, The Magic Lantern, where he says:

The film, entitled To Joy, was… about a couple of young musicians in the symphony orchestra…, the disguise almost a formality. It was about Ellen [his wife at the time] and me, about the conditions imposed by art, about fidelity and infidelity. Music would stream right through the film. […] Under the influence of a dawning hope of a possible future for our tormented marriage, the portrayal of the film’s leading female character turned into a miracle of beauty, faithfulness, wisdom and human dignity. The male part, on the other hand, became a conceited mediocrity; faithless, bombastic and a liar.

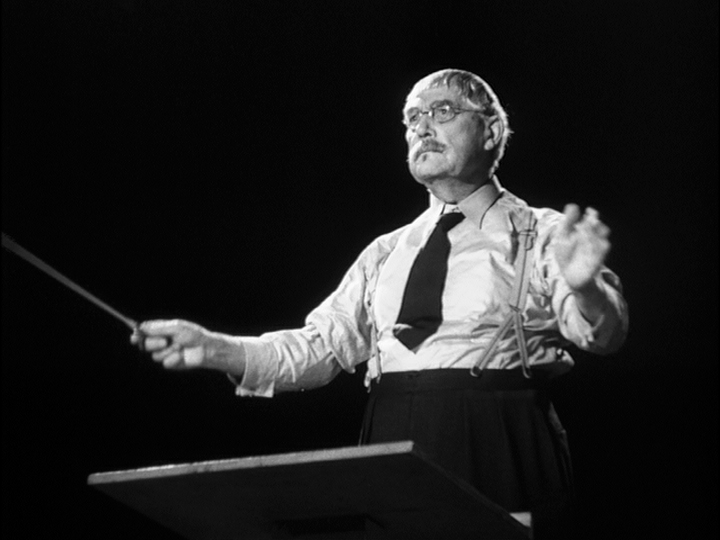

Beyond that, the film’s most notable feature is that it cast Victor Sjöström, most familiar to today’s audience as Dr. Borg from Bergman’s 1958 classic Wild Strawberries. Here he plays the part of Sönderby, an aging conductor who’s made his peace with the fact that he’ll never rank among the giants in his artistic discipline and seeks to convey that wisdom, sometimes sternly and sometimes with comical warmth, to the presumptuous young egotist too busy chasing his ambitions to see the human wreckage he’s leaving in his wake.

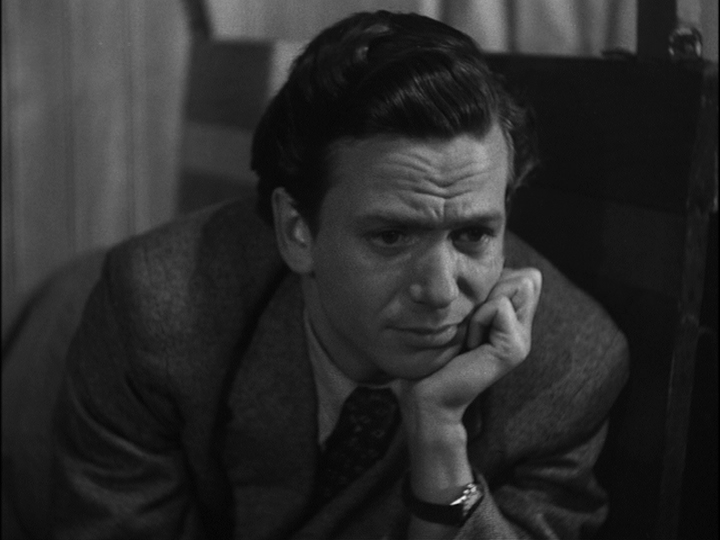

Left to live on their own terms, Stig and Marta might have had a chance to achieve a measure of marital happiness – they do like each other, with enough in common to remain compatible and enough creative friction between them to keep things interesting. The short video clip below, of a significant moment in their early courtship, captures their mutual attraction and ideals very sweetly. But of course no relationship exists in a void. Stig in particular is driven by a futile desire to achieve greatness, perhaps even a degree of immortality through his art, even though his talent is nowhere near that level. Intolerant of the mockery he earns from those who see through his facade, Stig is the epitome of the self-serving striver who masks his own fears of anonymity and insignificance by constantly pushing himself and those around him to transcend the limits of mere mediocrity. In his vainglorious pose, Stig is yet another example of Bergman’s inclination to make his films a form of confessional, a safe haven in which he can air his dirty laundry, exposing his monstrous character flaws and thus provide some relief for his tormented conscience, all the while giving his audience an opportunity to see various aspects of their own lives and domestic dramas unfold on the screen as well.

Marta’s brief reflections on the need for a meaning in life (even if it’s just made up) in that clip also point directly ahead at similar ruminations that Bergman will offer on the role of faith and purpose (or the lack thereof) in his films over the course of the next few decades. Over those years, his views refined and evolved, ultimately approaching a graceful (but not complacent) equilibrium after going through some of the most harrowing and excruciating psycho-spiritual exchanges ever captured on screen.

But in To Joy, we get a look at the younger, brasher Bergman, as we see his spokesman Stig lurch from being a drunken maniac ranting at Marta’s birthday party (where he’s the new guy in the orchestra creating a very bad first impression) to a soft-hearted loverboy wooing his attractive lady friend with a simple (but fool-proof) gift. Can’t go wrong breaking the ice with an adorable little teddy bear.

Stig’s philandering with Nelly, the flirtatious young wife of a bitter and grizzled old impresario named Mikael Bro, also echoes Bergman’s lifelong indulgence in that pastime, with his script giving the protagonist a freedom to play the field that the writer/director was trying his damnedest to suppress at the time as he sought to salvage his own marriage, to no avail as it turned out.

Around the same time that Bergman was putting the finishing touches on To Joy, “shamelessly exploiting” (as he put it) the grand and powerful music of Beethoven Ninth Symphony, he was also yielding to temptation. After shooting Stig and Marta’s wedding scene in the same town hall where Bergman and his then-wife Ellen had married a few years earlier, he met a film journalist named Gun Hagberg with whom he promptly fell into an affair that went on to provide crucial content for later movies like Scenes From a Marriage and The Silence. It’s left to the rest of us to relish the gratitude we feel for Bergman’s indiscretions that ultimately gave birth to those indelible cinematic treasures. (And yes, that’s Ingmar himself doing a cameo bit, breaking the fourth wall as he glares into the camera in a brief maternity ward waiting room scene.)

As Stig and Marta go through the trials and tribulations of their doomed marriage, Bergman does his best to balance out the portrait by showing us some of their joys and intimate moments. Especially effective are those times when, in the midst of their sorrow and pain, they find it within themselves to turn to each other as sources of support, in effect laying up some reserves of hope and resilience that just might lend them a bit more strength to face life’s inevitable storms. Though not planned, they give birth to twins and enjoy a season of life’s domestic comforts. When Stig’s big opportunity to flaunt his skills as a soloist ends in what a reviewer calls an unfortunate “premature suicide” after his violin falls out of tune, Marta is there to reinflate his crushed ego, be it ever so temporarily.

Despite these earnestly delivered gifts from Marta, Stig remains unable to summon the strength to uphold his marriage vows, inevitably meandering back to the degenerate companionship of Nelly, Mikael and the smirking demonic Marcel. Bergman succeeds in making Stig a fairly detestable character, a virtual surrogate of himself as an artist still looking to establish himself and rise to the level of mastery that he felt capable of but at this point in his career had still not achieved.

It remains an interesting bit of speculation as to what role all the real-life interpersonal crises and heartaches caused by his behavior played in facilitating Ingmar Bergman’s rise to prominence in his chosen media of theater and film. There can be no doubt that the tempestuous dramas that accompanied his affairs, his divorces and the strains it created in his other relationships provided all sorts of material that his sensitive observational powers then transformed for the purpose of thought-provoking entertainment. But could he have been as great an artist as he turned out to be if he’d somehow found a way to settle down and do right by the women and children in his life? To Joy seems in part to be an acknowledgement that he could not, that in some way, a relentless dedication to his art made it practically impossible for him to offer the concessions necessary to maintaining a happy home.

By supplying Stig a convenient escape from the irritations of an aggrieved conscience through his wife’s sudden untimely demise (a contrivance that Bergman admits may have been “secret wishful thinking” on his part), the writer/director simultaneously renders his massively flawed protagonist a bit more sympathetic – after all, Stig’s a widower now, with two young children to raise on his own – and tosses himself a soft pitch for an “art conquers all” finale that Bergman proceeds to slam out of the park with a stirring rendition of the Ninth’s final movement, the chorale “Ode to Joy.” Though I have to say, it’s difficult for me to either completely disregard or completely buy into the manipulative charms of this last scene. I mean, who isn’t moved to some degree by that magnificent music? And when you combine that with Gunnar Fischer’s exquisite cinematography, the effect is nearly irresistible. Still, I take it all in with more than a shade of ambivalence, knowing the price that many others paid in order to purchase Ingmar’s creative license. What I appreciate most in To Joy‘s closing moments is the quiet entry of Stig’s son Lasse, whose role as a silent observer, hardly comprehending the full scope of what the choir and symphony are expressing through their music, reminds the adults in the room that indeed, as a different and earlier Criterion title puts it, the children are watching us.