I haven’t felt this far behind the curve on a new Eclipse release since right around the time I began writing this column in 2010. For reasons somewhat beyond my control (other than just going out and buying the set myself,) it took me a lot longer than usual to obtain my copy of Eclipse Series 32: Pearls of the Czech New Wave. It came out at the end of April, and has already been replaced as the newest addition to the series by their recent Up All Night with Robert Downey Sr. collection. Regular readers here may have noted my strange silence regarding the obscure offerings from the old Czechoslovakia, perhaps even wondering if I harbored some kind of animosity or indifference toward these films. No, such is not the case – I just didn’t have the opportunity to check them out, so I filled the void in other ways. But this precious box of pearls did at last make its way into my collection recently. My plan is to dedicate this column for the next several weeks to going through the films here individually, making up for the lost time.

Since this is my first significant encounter with Czechoslovakian cinema (other than a chance viewing of Closely Watched Trains some years ago without any benefit of context to understand what I was watching), I’m approaching these films as a highly curious novice, eager to latch on to the culture’s perspective and sensibility as it comes through these films. The six titles in this set were all released during a period of political reform in the mid-1960s, when Czechoslovakia attempted to recalibrate its subservience to the Soviet Union and the Warsaw Pact and ease up on the censorship and repression just enough to allow their people some intellectual breathing room. The experiment didn’t necessarily end well, with Soviet tanks and troops moving in to reassert control in the summer of 1968. But for a few years, the relative openness combined with Czechoslovakia’s legacy of occupation, repression and corruption created a very fertile environment for acerbic cinema to convey messages that, through cleverly constructed metaphor and subtly subversive satire, tested the limits of how far free expression could range in a Communist regime.

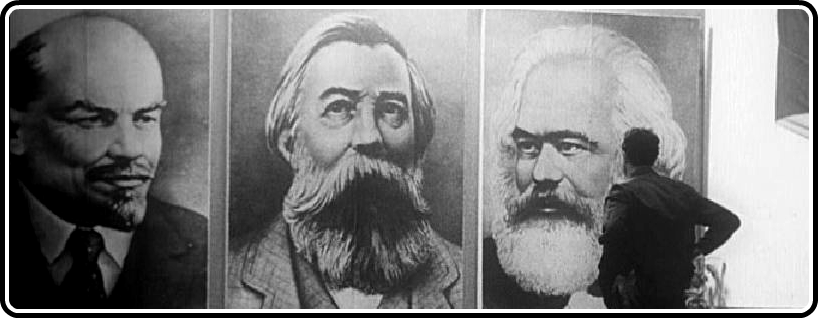

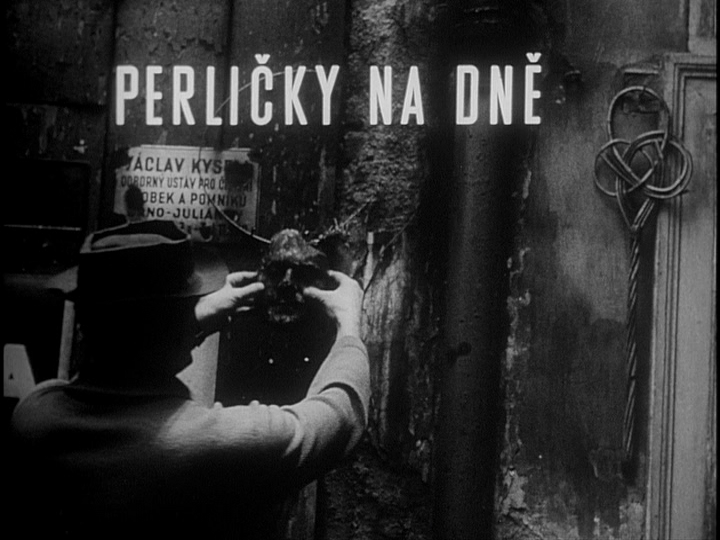

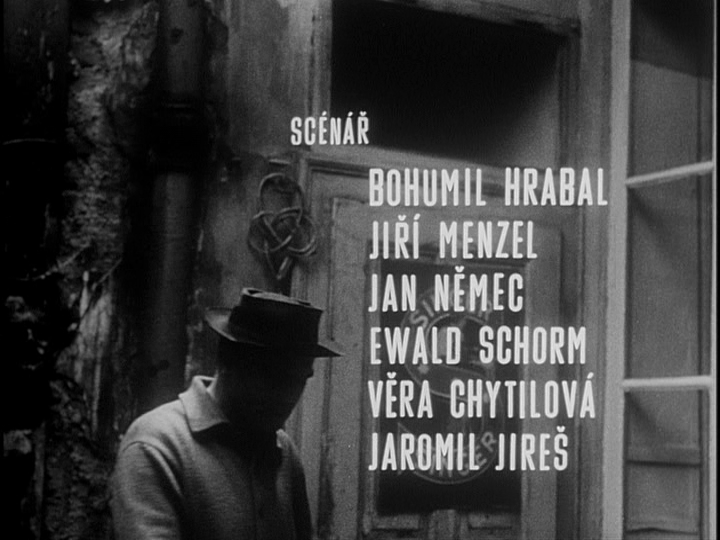

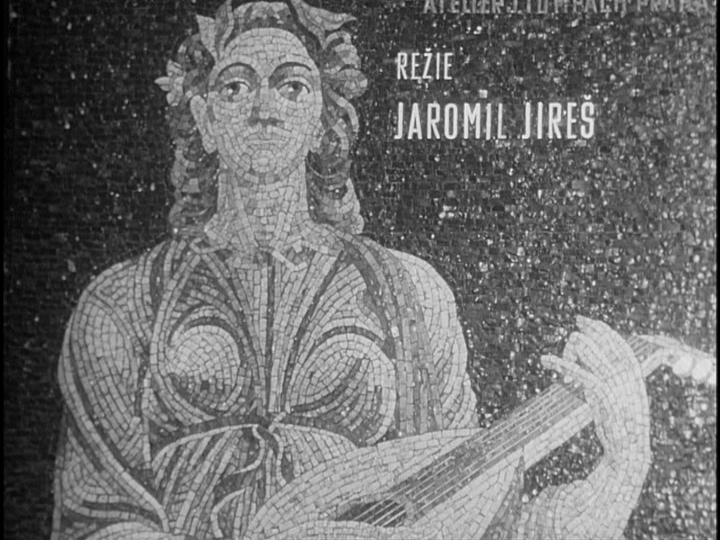

Though it wasn’t by any means the earliest example of the Czechoslovak New Wave, Pearls of the Deep provides the ideal introduction to this set and the movement in general. It’s an omnibus film consisting of five adaptations of stories by writer Bohumil Hrabel, one of the country’s leading literary figures of the time and for decades afterward. Hrabel appears in the opening credit sequence above and also make brief cameos in each of the other shorts, each shot by a different director, but the same cinematographer, Jaroslav Kucera. Each tale is a small slice of contemporary life in Czechoslovakia, and though it may not necessarily be by design, there’s a general shift in perspective from the concerns of elderly people in the beginning of the film toward a more youthful frame of reference with each successive story.

The first story is Mr. Baltazar’s Death, in which we accompany an middle-aged couple and one of their fathers to a motorcycle road race that they’ve been attending for quite a few years. The focus is on their mildly bickering banter as they work on their broken down “1931 Walter” convertible/potato-hauler and dispute the make and model of passing vehicles based on the sound of their engines, openly swigging bottles of brandy as they make their way through the woods to the big gathering.

The competition draws a crowd of bystanders who position themselves at strategic curves and intersections to catch the action. Some position themselves in hammocks perched from tree branches high above the audience below. Director Jiri Menzel puts us in the midst of the festivities (which are clearly filmed during an actual race, not staged for this production) by using a semi-documentary/improvisational approach that readily connects us with other filmic New Waves. For aficionados of old-time motor sports or gearheads in general, there are some cool throwback scenes featuring cycles and racing paraphernalia of a bygone era. The humor contained in the meandering conversations between random characters is nuanced, not glaringly obvious, and may deliver more amusement the second time through, after one comes to appreciate the relationships between the old codgers, who tend to prattle on talking past each other, unraveling their anecdotes in an interwoven strand.

Once the race itself begins, Menzel captures the beauty of vehicles in motion by pairing the graceful fluid images with a lush accompaniment of syrupy string music that’s not so different (other than the obvious reduction in scale and grandeur) from what Stanley Kubrick with spaceships a couple of years later in 2001: A Space Odyssey. That is, until the inevitable high-speed wipe out occurs, giving the spectators the bloody payoff they all anticipated and that makes these technology-enhanced competitions so morbidly compelling. As the old couple drives off with a fresh set of wreckage-related stories to tell each other next year, the viewer is left feeling slightly uneasy about the casual acceptance of wasted lives for the sake of an afternoon’s entertainment. Menzel’s point, exactly…

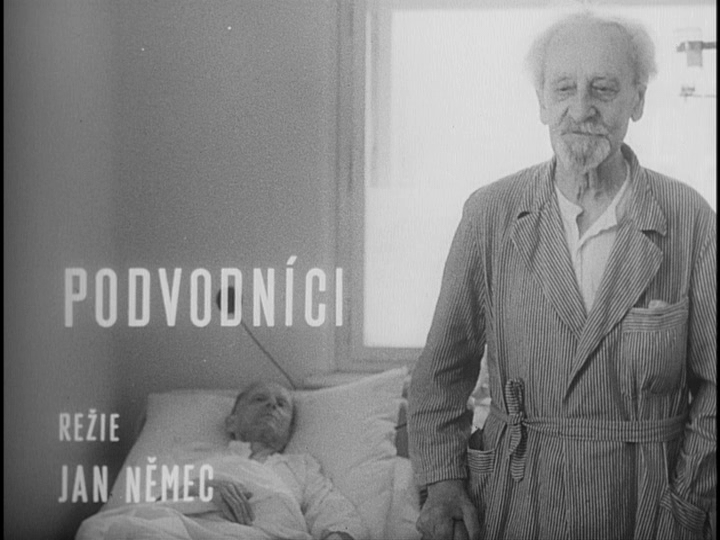

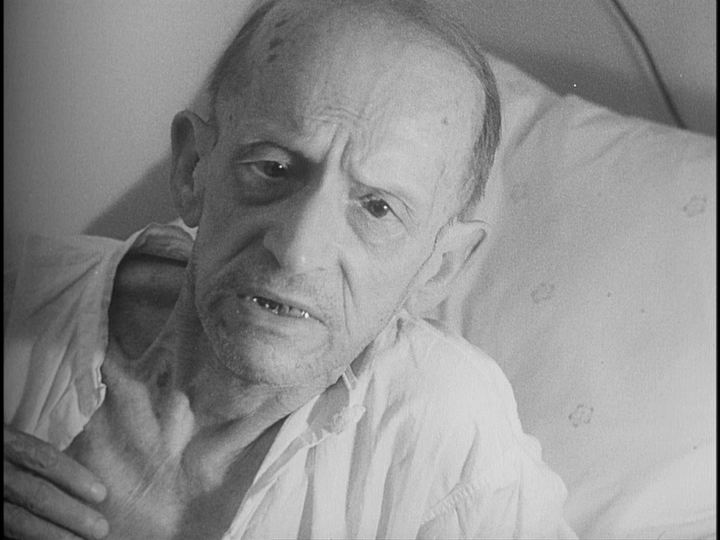

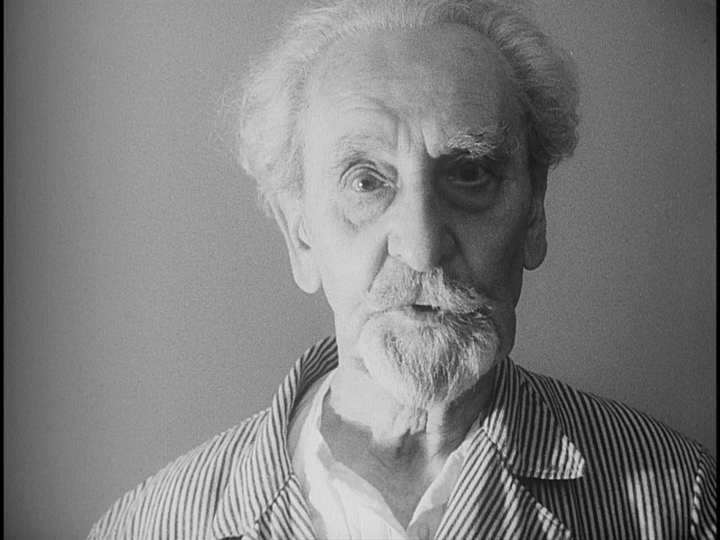

The Imposters, directed by “enfant terrible” Jan Nemec, is the second installment, probably the most easily grasped story of the bunch here. It’s a simple narrative, consisting mainly of a conversation between two inhabitants of a nursing home who look to be pretty close to the end of their earthly journeys. Left largely to themselves, they have little else to do to while away life’s swiftly ebbing days but reminisce with each other about the important men they used to be back in their prime, sifting through their physical and mental memorabilia to present the evidence that reminds them of the applause and admiration their work once generated.

The bed-ridden and more decrepit of the two used to be a stage performer who’s more than happy to break out into song, reprising some of his past show-stoppers, if only to stave off the bitter memories of the various losses and rejections he’s endured. His upright counterpart plays verbal ping-pong with him, recounting his career as an award-winning investigative reporter who fearlessly uncovered scandals of corruption in high places. As the segment’s title implies, however, there’s more than a little bluff behind their recollections, setting us up for a provocative twist that speaks truth about how seamlessly hypocrisy had been woven into the official version of things in Czechoslovakian society, a problem that continues unabated in our own.

Pearls of the Deep‘s one respite from the monochrome palette occupies the central section of the film, in Evald Schorm’s The House of Joy. While all five of the shorts can be considered fascinating character studies, this one features the most notably eccentric: painter Vaclav Zak, who basically plays himself as he walks a pair of government-sponsored insurance salesman on a guided tour of his home and farmstead.

The house referred to in the title is nothing all that special architecturally, but its decor is utterly unique. Just about every flat surface (including floors and ceilings) has been transformed into a canvas for Zak’s fertile realization of his dreams and imaginings. His home is quite a repository for his distinctive naive art, and I’m quite curious to know if the place was preserved at all after Schorm captured the work so nicely on film. Numerous close-ups of Zak’s miniatures, featuring gnomes, princes, animals and natural landscapes provide ample material for a nice Tumblr post (maybe I’ll get around to that…) But the gist of the story is the contrast in how life is viewed by the perpetually enchanted artist, his blunt-talking wife and the two perplexed agents trying to take care of their business. The old couple function as a force of natural, apolitical anarchy, blithely and unintentionally complicating the simple bureaucratic mission of tidying up their financial and legal affairs through “the interruption of an official act.”

The clip above demonstrates Schorm’s openness to more overtly symbolic and experimental film-making than any of the other more reality based pieces in Pearls of the Deep. The flashback to an incident where a crazy-eyed crucifix was posted at an intersection leading to much calamity raises the bar of weirdness to a new level, incorporating over- and undercranking film effects and mock-grandiose musical accompaniment to skewer both the local brand of folk-religion and the smug confidence of doctrinaire Marxist atheism at the same time. Rather than pointing toward a triumph of one force over the other in some kind of apocalyptic showdown, The House of Joy‘s message reminds us that “some things should be left as they are.”

Color quickly drains off the screen as we transition from the joyful house to The Restaurant The World, directed by Vera Chytilova, whose Daisies is the film that’s drawn the most individual attention in this box set. (That will be the subject for my next post to this column.) Whereas that film is a wildly colorful immersion into surrealistic extravagance and absurdity, The Restaurant The World shows that Chytilova could work just as effectively within a more constrained set of artistic guidelines. The story begins with the discovery of a dead woman in the closet of a restaurant. Next door there’s a boisterous wedding reception going on. The restaurant’s customers are hastily cleared out, the police are contacted, and we’re led to expect that some kind of murder-mystery story will proceed from there. Well, there are plenty of mysteries involved, but none of them resolved in the conventional sense.

Rather than focus on and develop a central character, or focus on the forensic details that led to the nameless woman’s demise, Chytilova presents us with a procession of individuals who each have their own enigmatic response and involvement with the tragic incident. The restaurant staff are mostly passive bystanders who nevertheless bear some responsibility to manage the strange interruption to their routine. The restaurant customers who were kicked out after the corpse was found refuse to leave altogether, lingering outside the window, waiting to come back and finish their meal. The reception guests continue to sing and carry on (from what we hear on the soundtrack, which often has no correlation with what we see on-screen.)

The two characters who leave the strongest impression are a disaffected artist, who works with industrial metal and other media, and the bride, who only enters the scene toward the end, after something unexplained occurs off-camera that leads to the arrest and detention of her husband. The artist had entered the restaurant grieving the sudden disappearance of his fiancée, and winds up leaving it with the newlywed woman who simply doesn’t wish to spend her bridal night alone, even if it means choosing a different companion than the one she planned on. Visual clues offered by Chytilova as the artist relates his recent past to the wait staff, and the eerie nightmarish sequence that concludes The Restaurant The World, lead to some tentative but disturbing appraisals of what might have happened… We never know for sure, but it’s a haunting, tantalizing short film that easily invites repeat viewings just for the sheer enjoyment of examining more closely Chytilova’s hypnotic blend of sound and vision.

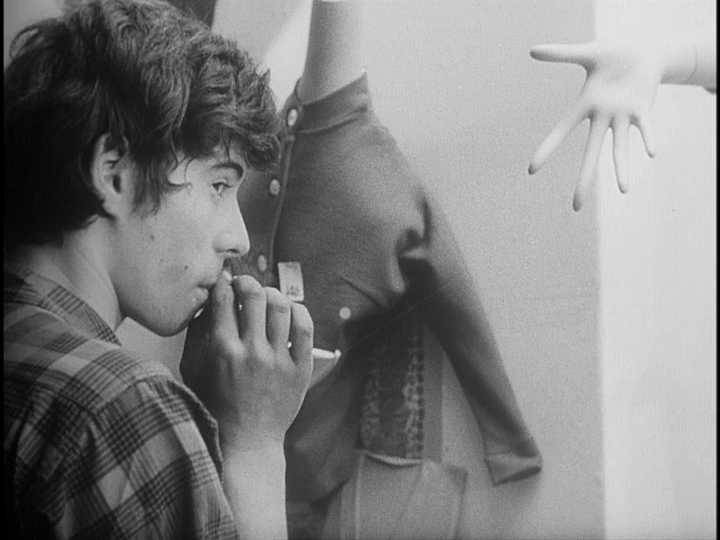

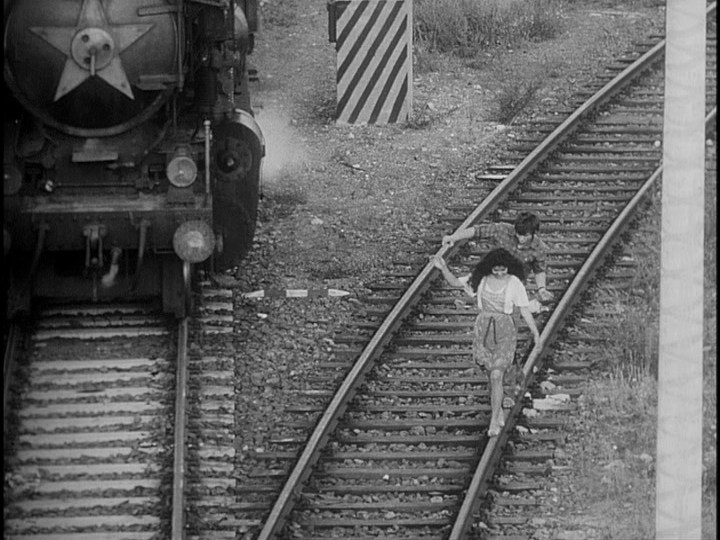

The ironically titled Romance wraps up Pearls of the Deep with the most overtly political and directly confrontational message found in this anthology. It involves an admittedly charming and romantically plausible pair of young lovers. He is Gaston, a Czech plumber, just coming into adulthood and making the adjustment to the expectations of a workingman’s life. She is Margitka, a pretty young Gypsy with bright eyes and long flowing hair who sees him eyeing her one afternoon as he emerges from a movie theater. He’s just watched Fanfan la Tulipe, a 1950s French swashbuckler starring action-hero/matinée idol Gerard Philipe and curvaceous Gina Lollobrigida as a tantalizing Gypsy beauty whom Fanfan falls for. Margitka is savvy enough to both detect and exploit his impressionable vulnerability to her charms, working her magic quickly and to full effect.

In the short span of time that Gaston and Margitka spend together, they develop an appealing chemistry with each other, provided one isn’t too put off by the unmistakable air of a confidence game that she is pulling over on him.

Sure, her motives are transparently ulterior, but it’s not like Gaston isn’t getting something pretty nice out of the bargain as well…

After we acquaint ourselves with the fresh young couple and accompany them through the usual hand-holding and sweet-talking rituals of newly found romance, the story takes its more provocative turn with a visit to Margitka’s home, an outdoor Gypsy encampment. Presumably the vast majority of Pearls of the Deep’s original viewers came from the Czechoslovak frame of reference represented by Gaston, with their own set of presumptions and prejudices about the Gypsy population that lived on the fringes of their society. Not being strongly attuned to the cultural conflicts and relations of that time and place, I still picked up on the implied affront to the notion that a centralized socialist bureaucracy and its attendant industrial manufacturing complex could ever rein in the untamed and non-conformist element in Czech society that the Gypsies embodied. The final shot of the film, which I won’t spoil here on the assumption that very few readers have had a chance to see it, delivers that message with mischievous juvenile glee.

Though I’m just beginning to dig into Pearls of the Czech New Wave, my early assessment is that this looks like one of the most essential Eclipse sets to be released in the past couple of years. These are films that will likely benefit from repeated exposure, especially since they come from a region and referential perspective that’s largely unfamiliar to many of us. They’re a fascinating by-product of a society that, like our own, flatters itself on being or even aspiring to a much higher standard of “freedom” than those in power are realistically willing to concede. By exploring the disconnects between the rhetoric put forth by the Czechoslovakian government and the dismal reality actually lived by its people, I suspect that there are many truths to be extracted from these pearls that can be meaningfully applied to our own situation.