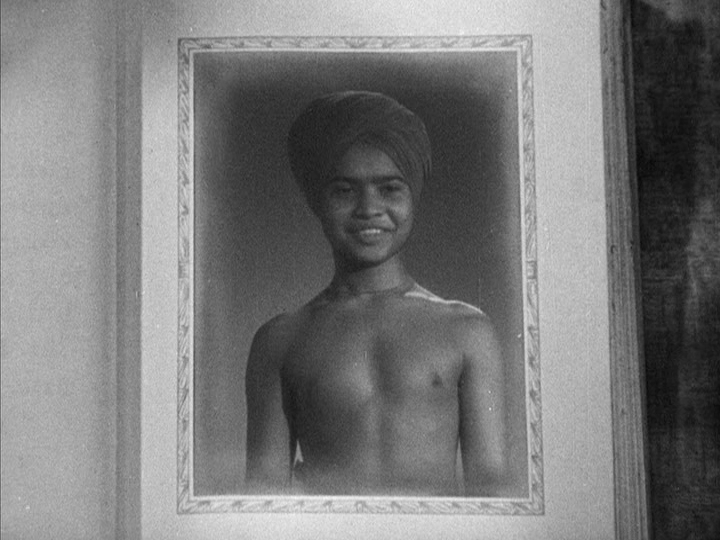

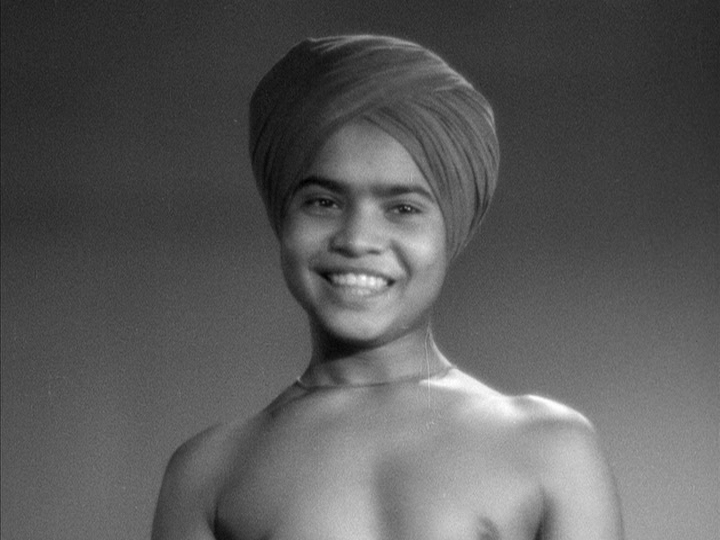

Last week, Criterion’s Eclipse Series reached a milestone in releasing its 30th box set, the first to be dedicated not to a director, not even to a writer or genre, but to an actor. As important as they are to the art of cinema, Criterion hasn’t exactly made a priority of putting performers front and center as their primary marketing strategy. But if they’re going to make an exception to that rule, I think they made an interesting choice in giving the honor to the one and only Sabu, an abundantly charismatic child from India who burst onto the screen in the late 1930s and truly brought a new face and force of character into the film culture of his times. So unlikely is his story, and so indelible is the impression that he leaves on viewers, that Eclipse Series 30 is adorned with just one evocative word as its subtitle: Sabu! Though some may view this box as a slight, even gimmicky collection of films, I find them each intriguing and distinctive works in their own right, so I’m following the usual format of this column to just focus on one movie for now: Elephant Boy, the one that started it all in transforming the young orphaned servant boy Selar Shaik into a remarkable cross-cultural international movie star.

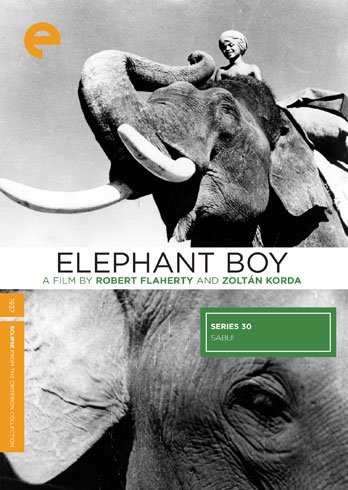

Based on a short story, “Toomai of the Elephants” by Rudyard Kipling, Elephant Boy seems like it was developed to compete with the popular Tarzan films and similar examples of jungle-based entertainment. The story’s blend of stirring adventure and exotic settings made it a fairly safe bet to click with fans of the Ape-Man, especially with veteran documentary filmmaker Robert Flaherty scouting out village life and wilderness scenes in the northwestern frontiers of India. Flaherty practically invented the nature-based documentary genre in 1921’s Nanook of the North and over the next few decades continued to take his camera into new and rarely filmed regions around the world. All he needed was the right kid to play the title role, of a young mahout (elephant driver) whose courage and rapport with the giant beasts gives him the last laugh and a hero’s rousing hurrah as he outwits the foolish and resentful adults who keep messing things up and underestimating his abilities – circumstances that youngsters in every place and time easily relate to and yearn for themselves.

For avid viewers of Criterion Collection films, Sabu’s familiarity has been established in roughly equal part by two notable performances, one as a supporting actor in Powell and Pressburger’s Black Narcissus and the other in The Thief of Bagdad, whereSabu pretty much steals the show, even against formidable competition from Conrad Veidt as the villain Jafar. The Sabu! set collects his two earliest performances (debut feature Elephant Boy and a colonialist epic adventure, The Drum), along with another jewel in his career, Jungle Book, which came out between The Thief of Bagdad and Black Narcissus.

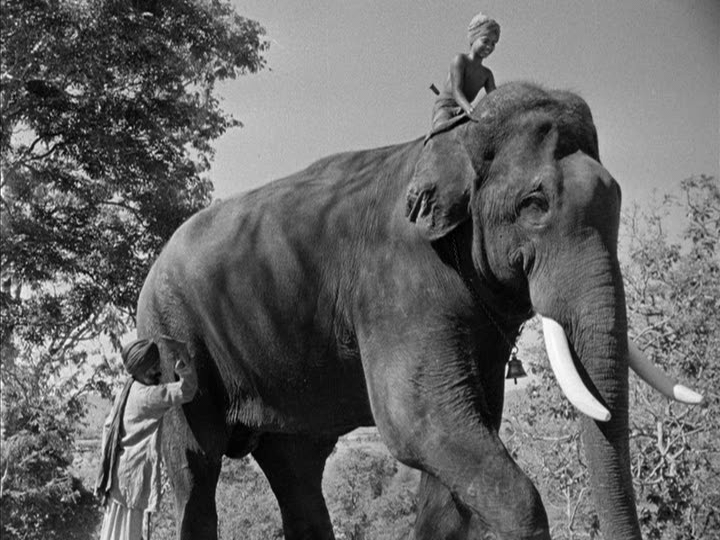

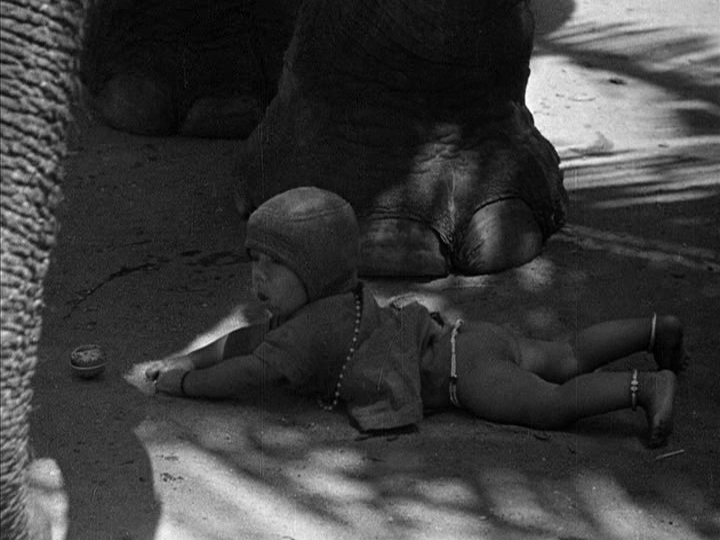

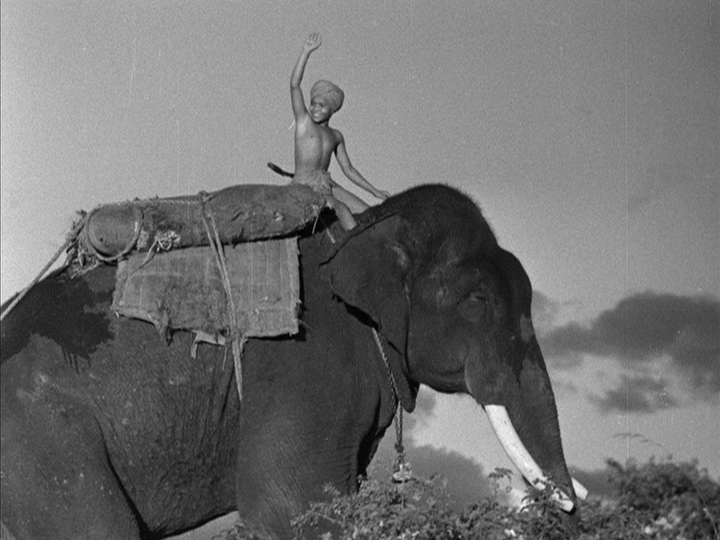

Elephant Boy starts with an wide-eyed and exuberant in-character monologue by Sabu giving us the background of his tale, before shifting into the narrative with a charming wake-up scene as the boy rises from his slumber along with Kala Nag, his tamed but mighty elephant and a wild monkey, all paralleling each other in their morning yawns, stretches and scratches. The humor is easygoing, the production values are simple and unadorned, but still capable of instilling a sense of amazement as we watch a small but scrappy kid effortlessly performing his own stunts, mounting the massive animal and leading him through jungle trails and city streets with ease. Sight gags like the elephant stepping over a half-naked baby laying in the streets also reveal a rougher, occasionally patronizing mindset behind the making of the film, informed as it is by all sorts of colonialist presumptions that make it very much a product of its time. It’s a bit jarring to realize the significant risks that the baby was subject to in making that scene, while at the same time enjoying a slight deviation from the corporate oversight and relentlessly commercial homogenization that governs most youth-oriented movies made nowadays.

This 10 minute selection from the early scenes of Elephant Boy shows Sabu in action, tending to his elephant in an Indian river as he and his peers prepare to ride alongside a big hunting expedition. It’s a marvelous little display of Sabu’s natural ease in handling elephants, putting us in touch with a fascinating environment and way of life that obviously thrilled its initial audiences and still casts an alluring spell today.

The contrast between the wan, pasty British sahibs and the hordes of complacent, servile natives who vastly outnumber them but still follow their orders and submit to the imperial authority over their ancient civilization, comes across as regrettable for the most part, though not nearly as presumptuous as Sabu’s follow up feature, The Drum. Our perception of the resolute men in charge, and what to make of the fairly petty and inconsequential challenges to their leadership throughout the film, registers quite differently in the 21st century than Elephant Boy‘s creators ever intended or imagined.

While the cultural baggage of the “great white hunter” stereotype is never entirely absent from the proceedings, it’s thin enough to set aside in most parts of the film, especially when the action focuses on Sabu and his exploits against the forces of nature and greedy, manipulative adults. And in spite of that veneer of smug superiority, the documentary aspects of Elephant Boy do serve to deepen our familiarity with Indian culture to some extent, a welcome development as Criterion continues to introduce more films set in that part of the world. 2011 saw the introduction of Satyajit Ray into the Collection, via The Music Room, and though I’m reluctant to rank Elephant Boy on the same level, there’s sufficient authenticity here, via the music and local scenery, the flora and fauna, to give this film more heft than one might expect from a quick glance at its juvenile subject matter.

And no matter how you slice it, the sight of a 12-year old Sabu sitting atop his elephant, expertly maneuvering the creature to hoist weighty timbers into place or weave through tight spaces, is a marvel to behold. Sabu’s incessant charisma and boundless energy as a screen performer is probably well-enough confirmed by his more famous appearances in subsequent films. To the extent that Sabu might be considered a “Golden Age Superhero” of international cinema, Elephant Boy serves as his origin story, showing that the boy had irrepressible talent from the get-go, that motion pictures just happened to draw forth and capture from him in a particular way. Though no one could have ever charted the trajectory of Sabu’s life from young orphan to movie star to valiant fighter in World War II, and finally to an unfortunately early grave, the sheer vitality of the child we see on screen leaves the impression that he would have been a formidable person even if fate had not led him into a career in show business.

For a kid who had to recite his lines phonetically because he didn’t speak English, who had never received any training nor even aspired to be an actor or entertainer before he was recruited for the job, and whose life was drastically uprooted when he relocated from the Indian jungles to the heart of London to film his studio scenes under the direction of Zoltan Korda, Sabu turns in an impressive and emotionally affecting performance. He convincingly covers a wide range of emotions: playful enthusiasm, dejected grief, puzzled ambivalence and fiery determination as he realizes that he has to take matters into his own hands, in order to save the life of his beloved Kala Nag from the adults who would have him shot. Sabu is the smallest, youngest and least experienced of the people we see on screen, yet he commands our attention with nary a flub nor a missed beat along the way.

And due credit must go to the non-human members of the cast, namely the majestic elephants do their own share of dominating the scenes in which they appear. For most readers, the only elephants we’ve ever seen have been the property of zoos or circuses. Even though it’s hard to deny that contemporary nature documentaries and hi-def video shot more recently than the late 1930s surpasses the images of Elephant Boy in sheer technical quality, I can’t think of too many films in which the interaction between our two species is more integral or evocatively rendered than this one. And as far as pacing is concerned, Korda and Flaherty do a great job steering the plot toward a truly impressive, or shall I say mammoth, gathering of prize specimens in Elephant Boy‘s rousing, trick-photography and jungle-drum fueled grand finale.

Though not as familiar or as celebrated as Sabu’s later appearance in Jungle Book, Elephant Boy is absolutely the kind of film that I wished I had known about and shown to my kids when they were younger. Sure, we’d have our talk about the sins of colonialism and the racist ideology that made it possible, but that conversation is a necessary one to have with one’s kids and a film like this is a great facilitator to put those issues on the table. Transcending the paternalism of its time, Elephant Boy is a triumphant tale of empowered youthfulness hood that evokes the best of childhood memories and emotions. It’s not too often that one can give a solid recommendation of Criterion-related films as “family friendly,” but Eclipse Series 30: Sabu! is without hesitation a great gift idea for any pre-adolescent cinephiles on your holiday shopping list.