With Iron Man 3 opening this weekend, functionally serving as the unofficial kick-off to the 2013 summer blockbuster movie season and generating all the buzz one would expect in the online movie blogging world, I could not have chosen a more incongruous film to immerse myself in over these past several days than Criterion Spine #650. A Man Escaped represents the antithesis of just about everything that cinema has become at this stage of its development, not only in the obvious contrast to standard Hollywood commercialism but also in regard to what’s happening in the art house realms as well. Already seen as a singular voice of stubborn discipline and unswerving commitment to the principles of his art back in his prime during the late 50s and early 60s, the stripped-down rigor of Bresson’s production methods, his disdain for any hint of overt sensationalism and refusal to use special visual effects in conveying his message now stands without any apparent contemporary parallel, though indications of his influence can certainly be pointed out here and there. Now, with five Bresson titles already issued on DVD over the past decade plus, Criterion has graced us with a home video package that offers the ideal introduction to an auteur whose name and reputation undoubtedly drew in a fair number of inquisitive cinephiles who, having sat through films like Au Hasard Balthasar, Pickpocket or Diary of a Country Priest, found themselves shrugging a bit at what all they hype was about.

It was never my plan to watch A Man Escaped just as this year’s latest crop of spectacular fantasy and sci-fi adventures are about to be unleashed, but that’s how it wound up. I received my review copy of the new Criterion release back in late March, but before I had a chance to write up my thoughts on the film, I saw Josh Brunsting’s review on this site. It didn’t make sense to me to have two articles about the same release published on Criterion Cast that close together, so I turned my attention to other films for the next month or so. After finishing my recent review of Billy Liar, an English comedy about a young man whose over-active fantasy life provides a measure of release from the doldrums of his boring life, it seemed appropriate to look at another film that dealt with escapism, only this time in more concrete, life-or-death terms.

Now, having made my way through this week’s social media onslaught of wearisome “May the Fourth” Star Wars jokes and all the commotion generated by audiences anticipating fresh servings every weekend between now and Labor Day of huge explosions, charismatic celebrity/actors, witty banter, otherworldly vistas, physics-defying action sequences and cataclysmic doomsday scenarios… I just have to admit, I’m feeling a bit curmudgeonly and out of touch with all that. And that’s perfectly fine with me! My week with Bresson, mediated by the excellent supplements found in this outstanding edition, allowed me to delve more deeply than ever into his artistry, even though I’ve seen all of his previous Criterion releases and found each of them rewarding. I feel like I finally made some headway into assimilating his profound vision of film and life into my own, and that more than makes up for whatever I may have missed by steering clear of the cineplex during that time. This review focuses more on the overall value and contents of this recent release than it does on the film itself.

Criterion’s track record with Bresson has been to release his films in roughly chronological order, beginning with his second film, Les dames du Bois de Bolougne and on up through Mouchette, from 1967. None of his later films have been adorned with the Big C yet, and they skipped a few earlier titles along the way (though 1962’s The Trial of Joan of Arc and his final film, L’argent from 1983 are available on HuluPlus.) Without having seen any of those missing links in Bresson’s work, I can’t speak with credibility on their quality or how badly they are in need of a top-shelf Blu-ray release. But A Man Escaped has always seemed like a glaring omission, just based on what I’d read about it and the significant impact it made on the emerging French Nouvelle Vague in the years immediately following its debut in 1956. This famously austere, meticulously focused masterpiece marked the director’s entry into the mature phase of his work, achieving a degree of perfection in stripping away the extraneous elements that Bresson himself found so distracting in conventional cinema as he worked toward the ideal he described as “cinématographe.” Though the term is typically translated as “cinematography,” what he’s referring to is much more than the mere operation of the camera or the management of a film’s visual elements. As is made abundantly clear and expounded on at length in the supplements, Bresson’s filmmaking philosophy (more fulsome in its development than a simple “style”) is more akin to painting than it is theater.

In Bresson’s extensive disclosure of the precepts he follows in the 1965 TV interview Bresson: Without a Trace, he speaks of himself almost as a pioneer who’s just beginning the process of developing this new form, hopeful that artists of the future would build on his achievements and supersede his work. How sad for us that he appears to have misplaced his confidence in that regard! His critical comments on what he regarded as the dismal state of the movie industry back in the mid-60s makes me shudder to think of how he would assess the situation today. Still, Bresson’s brilliant litany of aphorisms that explain his approach and the wonderful offhand quotes of thinkers like Dostoevsky, Pascal, Stendhal and others clearly demonstrate his dedication to the arts and the depth of his vision, as cantankerous as it made him at times.

The next major bonus feature on the disc is The Road to Bresson, a 1984 documentary from the Netherlands that catches up with Bresson at the tail end of his career. Two young men take it upon themselves to coax an interview out of Bresson, despite his notorious aversion to publicity. He yields for just a few minutes at the end of the hour-long film, softened up a bit perhaps by his appearance just beforehand at the 1983 Cannes Film Festival, in which he and Andrei Tarkovsky both appear on stage to receive jury honors presented to them by none other than Orson Welles. Bresson’s brusque reply to the very limited and exclusive opportunity he granted his youthful admirers is a marvel of sharp-tongued aesthetic irascibility. Excellent observations from Tarkovsky, Louis Malle and my fellow Calvin College alumni Paul Schrader offer additional insight as they pay their respective tributes to an artist who significantly affected each of them as they went on to create their own impressive cinematic legacies.

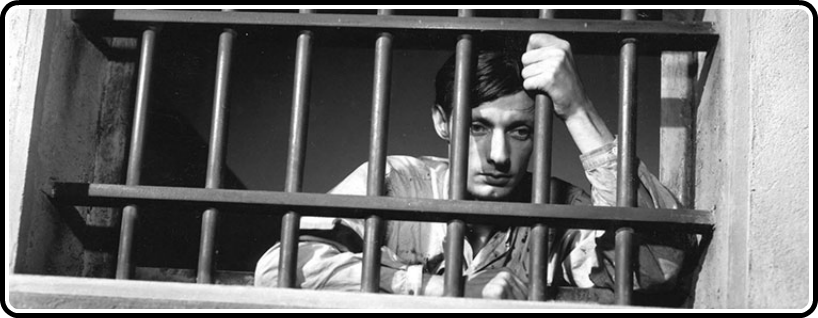

The last of the three documentary pieces that elevate this blu-ray package to “must own” status is from 2010. Titled The Essence of Forms, it’s a look back at Bresson’s oeuvre from a 21st century perspective, featuring interviews with several of his former collaborators, including Francois Leterrier, who portrayed the prisoner Fontaine in A Man Escaped. He begins his comments with a candid admission that Bresson, purist that he most certainly was, would likely be adamantly opposed to the idea of his films being sold for private home viewing on TV screens, not to mention the very sort of explanatory supplemental features he was in the process of helping to make. The anecdote captures in an amusing irony just how much of a conundrum watching Bresson can be in today’s world. Decidedly old-fashioned in his adherence to a unique code of filmmaking ethics that allows for no meaningful compromise for the sake of broad commercial appeal, Bresson’s quiet, deliberate pacing and the subtlety with which his films’ emotional payoffs occur demands a degree of close observation and shutting out of all other distractions that present quite a challenge for many of today’s cultural consumers. These aren’t the kind of films that give themselves over easily to live-tweeting, for instance, and even a few moments of diverted attention can quickly break the spell that Bresson so meticulously weaves.

One of the commentators in this short documentary refers to Bresson’s “liturgical” style of filmmaking, and that concept had indeed occurred to me as well when I was rewatching A Man Escaped. The film itself, concerning the single-minded focus and elaborately prepared break-out plans of a man condemned to be executed in a German POW camp during WWII, creates a subdued but compelling sensation of suspense the first time through. However, the cumulative impression it makes isn’t really felt until one ponders the experience afterward, and better yet, participates in the ritual at least another time or two, and with some degree of regularity after that. In our vicarious accompaniment of Fontaine through his suffering, perseverance, creativity and the steely execution of his journey to liberation, we too can draw a measure of boldness and inspiration in our own struggles to overcome the limitations imposed upon us. This is the kind of life-changing perspective that keeps me coming back to classic films that inform me along the way in my journey through life. While I’m able to find occasional enjoyment in the bucket of popcorn and a cool cup of something sweet and fizzy that go so well with the latest franchise installment down at the local 20-screener by the mall, Bresson’s cold, thin ladle-full of jailhouse gruel still offers more of the nourishment I crave for my gut, my bones and my brain.