The cameraperson seldom gets enough credit. While the director is mostly responsible for guiding the process and making crucial decisions regarding a film’s direction, they are less personally responsible for the image that appears on the screen. That comes from the cameraperson or cinematographer – often one and the same – whose experience shapes the film. They are always watching, and despite what the director intends, what the cameraperson sees is the specific image that is shown on the screen

The film also shapes the cameraperson. What they see cannot be unseen, and like any job, the residue of that experience can manifest into their personal lives. Such is the case with the documentary cameraperson, often anonymous, and they capture the reality of humanity, warts and all.

As a cameraperson, Kirsten Johnson has seen the absolute worst of human nature. She has filmed the personal costs of genocide, hate crime, political injustice, and war, lots of war. Her art is the manner in which she captures these images, finding a human element for the viewer to identify with. Her occupation is as much a war photographer as it is a cinematic cameraperson. She chooses challenging projects in distant lands, and even if she has hitherto been anonymous, she has been an artist behind the camera.

The film is an assemblage of footage from various projects that Johnson photographed. These shots did not make the respective finished films, yet were of interest to her. Sometimes they are asides, something regarding the making of the film perhaps. One instance is when she films herself trying to discretely photograph a political prison, only to get noticed and questioned by the authorities. There is another instance where she interviews a survivor of an atrocity who has lost most of the use of his eye, and she breaks down as he reveals how it happened. These moments begin as shots within the project she is undertaking, but they catch Kirsten’s eye, her passion. These are moments that made a difference to Kirsten, and that fit into the puzzle that is her life.

Even though we seldom see her face in the film, we know her as the omnipresence behind the camera. We feel her emotion for the subject. This is punctuated by the fact that interspersed between the documentary images are personal images, taken from her own collection. The same personal presence that we feel behind the camera is abundantly clear in these home videos. We understand her joy at seeing her twin children; we understand her painful curiosity as she probes the edges of her mother’s coherence. Similar stylistic mannerisms appear throughout her professional footage, and the contrast between personal and professional highlights what the scenes say about Kirsten. We understand why Kirsten fixates on a particular moment because we have seen something similar, through her eyes and lens, in her personal photography.

While Kirsten is the center of the film, she lets others speak for her. The voice of her inability to reconcile the trauma of what she witnesses comes from two of her associates. One associate, a war crimes investigator, describes how disheartening it is for him to see his subject in terror at revisiting places where horrific acts occurred. A translator is similarly traumatized, and at one point in the film, she points out that what they witness does take a toll. “We take it in,” she says, and there is no easy outlet. Kirsten, as the cameraperson, has a stark visual memory of this pain. She is responsible for being the witness, having seen and captured the tragedy. She takes it in too, and the weight of the film is exactly as these associates describe. In some respects the film is an unburdening, a coming to terms with what her subjects have revealed.

The vignettes are shown without contextualization save for the location (if it can be provided). The film consists of a series of scenes, some of which will recur or will connect later with others, and some of which are just visited that once. They require a challenge from the viewer, for us to “take it in” and make our own conclusions about who Kirsten is and what these images mean to her. They all add up to tell her story, to convey who she is, and it is a beautiful thing that she has access to such compelling footage in order to share her story.

There are some momentous scenes that will stick with the viewer. They can feel like a gut punch, and not just in the tragic sense like the documentaries that Kirsten works on. Occasionally we see pleasant images and moments, where rage is quelled or sorrow exhibited. They invite an emotional reaction because of how they are interwoven with what we know of Kirsten. They are also the connective tissue for us to understand how the film fits together, and as the vignettes are shown, the picture gradually becomes clearer.

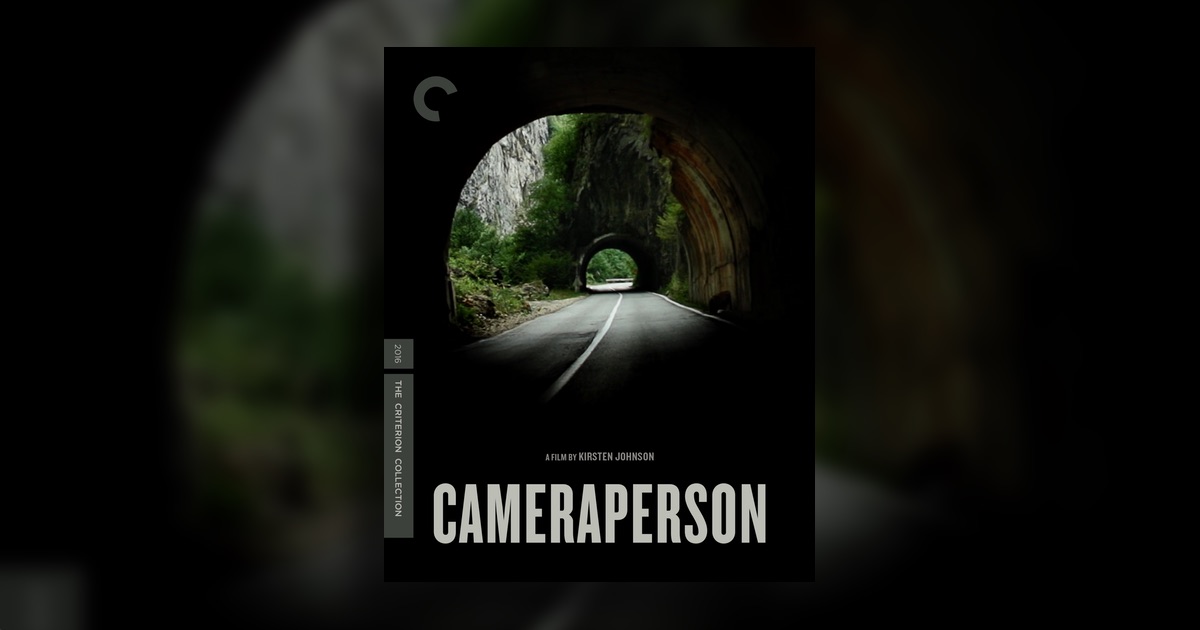

Cameraperson is an unorthodox documentary. In many respects it is an experimental film, one achieved through exhaustive trial and error, and it succeeds in ways where conventional storytelling falls short. The unique style is a product of not just Kirsten’s profession, but also her persona. She has the talent and experience in her craft to capture such vibrant images, but she has the personal fortitude and artistic sensibility to lay bare her soul in a uniquely revealing way. Her movie is about herself and her experiences. It comes from herself, and her channeling of a visual medium. It elevates the genre and is one of the most impactful documentaries I’ve seen in ages.

The Criterion edition includes several features that shed insight behind the project. Making Cameraperson and In the Service of the Film are discussions with Kirsten and her associates that cover the genesis of the film project, from the first cut of pure tragedy, to the “Chris Marker cut,” and to the final product. There are edited segments from two film festivals, one with Michael Moore and the other in Sarajevo, Bosnia. Often film festival interviews are light and not too insightful, but both of these are well worth watching. Also included is Kirsten Johnson’s 2015 short film, The Above, about a mysterious balloon that flies over Kabul, Afghanistan.

![Cameraperson (The Criterion Collection) [Blu-ray]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/4195wYH5RAL._SS520_.jpg)