Recognition is a funny and fickle thing. This is especially true in art, where often one’s accomplishments aren’t recognized until after the artist is dead. We live under a collective myth that simply creating something of quality is enough, even though it’s plain that it’s almost never that simple. Attention is hard to corral, and there’s simply far too much going on for many incredible things to be noticed. Talent, skill, and hard work matter of course, but you also need a lot of luck.

The musicians that Ry Cooder found in Cuba were long forgotten. Many of them had been stars in the 40s and 50s, but most were now languishing in poverty. More than that, they were no longer able to make their art. The records they made together, along with this film, gave quite a few of them the best years of their lives. More than the financial gain, it gave them recognition. It let them be treated like the marvelously talented people they were. It let their art be noticed again.

More than anything that’s what comes across as you meet these people. The sheer joy in being able to tell their stories. The incredible fun they are having making this music. These are artists who have been overlooked for a very long time. They are clearly both humbled and freed by the experience. The nature of the world music phenomenon, where rich nations pay for the art of poorer ones, is clearly a mixed proposition, but it’s not hard to enjoy the effect on the lives of these specific people.

Even more than that, we are all so lucky that this project happened at all. As someone who is currently making a podcast on the history of jazz (shameless plug here), I’m painfully aware of how much of that history has been forever lost. We have precious few primary sources from the early days to draw on. How much richer would our understanding of that history be if a Ry Cooder had been able to do something like this when those musicians were still alive. Many of the people featured in this film died just a few years after it came out. We’re all so fortunate that we get to hear their brilliance.

The documentary looks terrible, even in this new restoration. That’s not the fault of Criterion. It’s entirely due to the circumstances that surround the making of the film. As Wim Wenders explains in the special features, he had virtually no time or resources to make this project happen. Instead he took a cameraman and some early DV cameras to Havana to film. A lot of this was shot with those first generation consumer cameras, and it’s very obvious. I agree with Wenders though, that the look aids the feeling of the film. Cuba as a whole is a USA-sanctions-imposed crumbling shell of its former grandeur. The equally crumbling nature of this already archaic technology matches oddly nicely with that aesthetic. Anyway, it’s the music and the people that are the stars here.

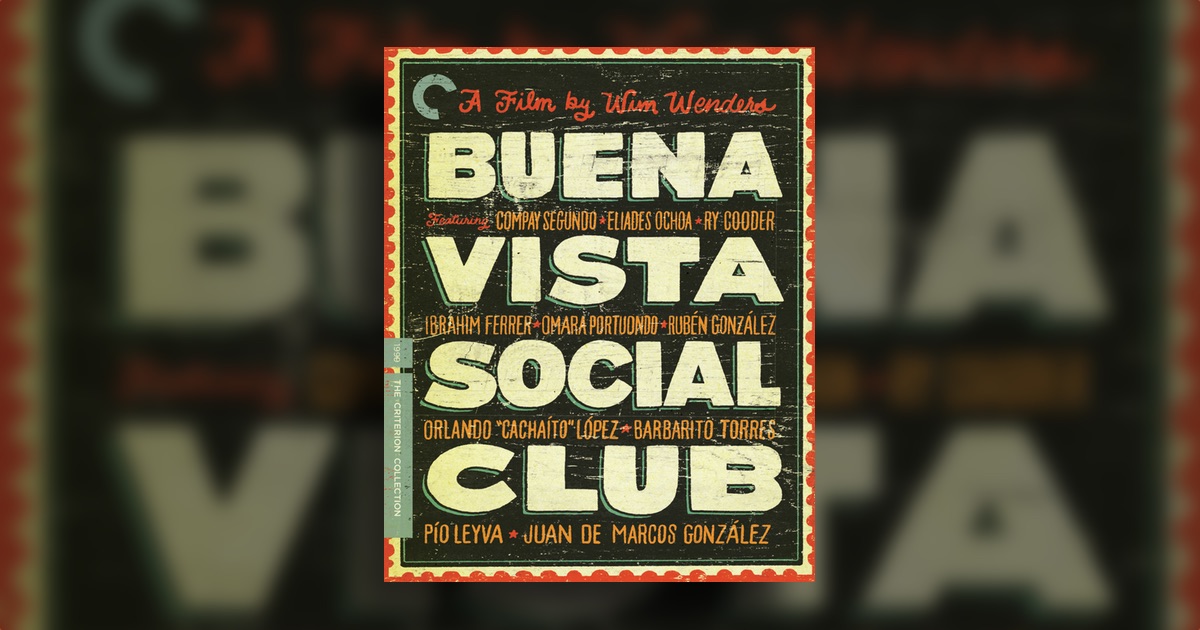

The special features on this disc are wonderfully comprehensive. We get an almost thirty minute long interview with Wenders, always someone I find interesting to listen to talk about process. He tells the story of how this all happened, and includes useful anecdotes. There is a treasure trove of radio interviews with most of the members of the Buena Vista Social Club. I haven’t listened to them all yet, but what I have heard is fascinating. There’s also an hour long conversation with Compay Segundo, who is perhaps the most interesting member to hear from. Finally we get some additional scenes, and a rare audio commentary, this one with Wenders from an earlier release. All in all it’s a great disc, especially for anyone who enjoys this music.