There exists little question at this time that The Passion of Joan of Arc is one of the greatest films of all time. Containing perhaps the finest performance ever committed to film, and committed in such a singular manner by its filmmaker, Joan remains an overwhelming, exciting, and deeply moving examination of one of history’s most notable figures. Far from being a stodgy courtroom drama, Dreyer’s film is a swirling, angular, wildly expressive reading of the transcript of Joan’s trial, upon which the film was based (though it presents a far more condensed depiction of the proceedings). The film is now famous for its near-exclusive use of close-ups – any random frame of the film has a fair chance of primarily featuring an actor’s face – which bring out the feeling of the trial whilst utilizing fewer intertitles than one might expect, given its origins and subject matter. In Dreyer’s hands, the courtroom drama is turned into opera.

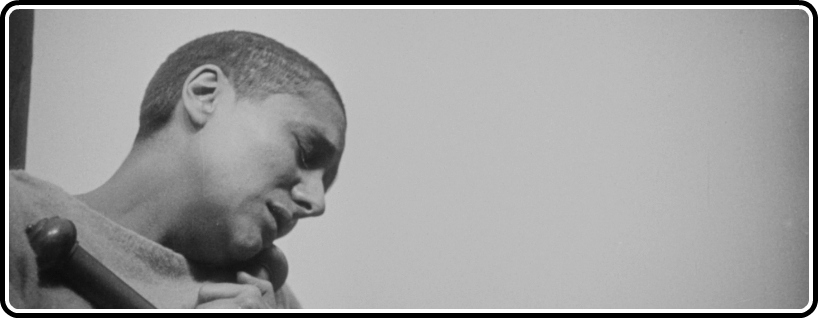

Only in cinema could the subtleties of expression be considered opera, and no camera could possibly accomplish what Dreyer was demanding of his actors, especially his lead performer. It is not exaggeration to suggest that Renée Maria Falconetti gives the greatest performance the screen has ever witnessed, and while I’ve not advanced nearly far enough in my own film studies to back up such a claim, nor would I dare to deny it. It’s not a role that demands a fair deal of complexity, as Joan maintains the kind of clarity of purpose we’re used to seeing in far lesser films, but Falconetti plays directly to the vulnerability of Joan’s position. This was a time at which the Catholic Church still very much stood in directly as God’s word to man, and their credibility in such matters was considered, or forcefully declared to be, infallible. That Joan is doubted by those around her is one thing, but the considerable doubt in must have caused in her is quite another. She is repeatedly shown to revere the Catholic practices of Mass, yet she is in direct opposition to the Church, which views her as a blasphemer, and perhaps even envoy of the Devil. So Falconetti sits before Dreyer’s camera, opening everything of herself, all she could ever be, leaving nothing at bay for the future film performances she’d never give (this was her last screen credit, having appeared previously in only two others).

That operatic feeling has been enhanced in the past by its most common companion score, most notably on the Criterion edition, by Richard Einhorn called “Voices of Light.” While certainly a dynamic composition, at times one can’t help but feel it seeks to change the film in some substantial way. Masters of Cinema, for their new (Region B locked) Blu-ray release, does away with this, and makes another key change – the actual speed of the film. As with many silent films, the playback speed has long been a source of controversy, with the standard 24-frames-per-second (fps) speed being applied merely by default. The folks at Masters of Cinema, however, went with research conducted by Dreyer scholars, as well as the Danish Film Institute (from which the print utilized in this release was sourced), and offer the film primarily as a totally silent feature at 20 frames per second (the 24fps version is presented for comparison and individual consideration).

This certainly presents a daunting challenge for any cinephile, raising the running time of the film by fifteen minutes, and without a score to boost. Though one is provided for each playback speed, the people at Masters of Cinema have specifically noted that Dreyer’s vision was for the film to run without any accompaniment. I’m not going to lie and say it’s magically an easier sit without the score, but it does provide a very different experience, one much more (if you’ll forgive the term) dispassionate than the “Voices of Light” version, but all the more in keeping with Dreyer’s vision, substantiated in the accompanying booklet, that this be a humanist, not a religious, take on the story. That the film remains an invigorating cinematic experience all its own is certainly worth noting, and the high points that any score would punctuate are communicated marvelously through Dreyer’s camera and intertitles, which he penned himself, lending his authorship a very real, tangible certainty.

As for the frame speed, I was rather surprised by what a difference it makes, especially comparing the two side-by-side. The 24fps version, which provided my first introduction to a film I love, now seems far too speedy, jittery, and more than anything, false. I expected a difference in the total experience of the film, but almost as soon as it starts in, I was struck by how “off” it all seemed. The great tragedy is that the score for this version is so much richer than either the “Voices of Light” version and, most unfortunately, the score accompanying the 20fps version. The latter, by Mie Yanashita, is appropriate and suitable, and probably more in keeping with how the film would have been presented in the late 1920s, but Loren Connors work on the former is staggering. Discordant and haunting, it perfectly evokes the spirit of the film without making of a big scene of it.

Whichever version you choose to play, the new restoration, conducted exclusively for Masters of Cinema, is everything I could have hoped for. Given its history (once thought lost, the definitive print was discovered in a mental institution in 1981), I’d be more than willing to forgive whatever issues it presented, of which there are miraculously few. It still contains a fair bit of damage, none of which was distracting in the least, and the notes on the restoration in the booklet maintain that any further attempt to clean up such marks would have left digital artifacts, a casualty I cannot abide and am thrilled to say I did not notice at all in this release. Even still, the film is almost always razor sharp, crisply reproducing Rudolph Maté’s landmark cinematography. Eyes are the windows to the soul and all, and our ability to see with even greater clarity every shimmer of Falconetti’s is central to the purpose of the film. This is one of those ways in which film restoration isn’t just about reproducing the film of celluloid, though it does, but in bringing out the central qualities of the story being told. It is integral.

The most common casualty of its age can be found in the flickering of the image, but for celluloid nuts like myself, this is part, parcel, and a great deal of the joy of watching old films. The contrast favors the booming whites in the image over more catchy deep blacks, a nice change of pace for the company. The film is naturally presented in its original aspect ratio, 1.37:1, and allows for all of the exposed image, resulting sometimes in the curved corners that often feel a little bit false, but here are integral as they are inherent to the film’s original photography. Nothing has been sacrificed here, and little has been enhanced – this is simply The Passion of Joan of Arc looking the best, I would wager, it ever has. The screencaps here come directly from the Blu-ray, but have been resized and compressed, so they’re but a hint at what this looks like in motion.

On the disc, one will find a restoration demonstration (posted below), as well as the “Lo Duca” version, which circulated in France and beyond during the years in which Dreyer’s true cut was thought lost. This version is edited down, and replaces the intertitles with subtitles. While certainly inappropriate in a true consideration of the film, it is of historical note, and I applaud Masters of Cinema for including it here for scholarly investigation. Thankfully, they didn’t waste any time restoring the 16mm print they present here, and the image quality alone should immediately avert viewers who stumble upon it.

Beyond that, all the special features are in the booklet, which eclipses even MoC’s usual ambition. Reaching a solid 100 pages, it features essays and shorter pieces by (deep breath now) scholars Jean Drum & Dale D. Drum, Andre Bazin, and Casper Tybjerg; poet and novelist Hilda Doolittle; filmmakers Luis Buñuel and Chris Marker; playwright and poet Antonin Artaud; and Dreyer himself; comparisons to the Lo Duca version, set designs and and other archival imagery, and a detailed note on the restoration of the film. The whole booklet is arranged expertly so that these disperate thoughts congeal wonderfully, forming a very complete image of the film as its lasting impact. Few films deserve this kind of extensive, wide-ranging consideration, and here MoC demonstrates how thoroughly this one does.

What else is there to say? This is Masters of Cinema doing what they do best – presenting an absolutely essential film from every reasonable angle, and presenting it magnificently. As they did last year with Touch of Evil, they’ve taken a film about which the presentation was very much in question, given us the evidence, and left you to decide what’s best. In the meantime, you’ll still get the prettiest version on the market. Watching a silent film in total silence may seem a daunting proposition, but I hope it’s a challenge you’ll accept, and should you wish to go with the score, two fine ones are provided. If you have a region-free Blu-ray player, the decision to order this is practically already made – this is one of the year’s most essential releases from any company, anywhere.

Buy the Passion Of Joan Of Arc from Amazon.co.uk