The late 1950s were a time of seismic upheaval and innovation in world cinema. In France, Francois Truffaut, Claude Chabrol and Jean-Luc Godard were backing up their boisterous critical rhetoric by placing themselves behind the camera and making movies the way they believed they should be made. English filmmakers were developing the kitchen-sink realism style featuring a lineup of angry young men. Ingmar Bergman brought Scandinavian cinema to global prominence, Italian film boasted the emerging talents of Fellini and Antonioni, and Japan unleashed an exuberant new generation of directors like Suzuki, Kobayashi and others who came out of the agitated rebellion of the Sun Tribe movement. Even India could put forth a prodigious genius like Satyajit Ray to introduce cinephiles from around the world to a culture that was ready to transcend the stereotypes and mystification that its recent colonial past had distorted. Among all the nations that could lay a claim to have shaped the medium of film in the earliest stages of its development, only Germany seemed absent from the larger conversation going on at that pivotal juncture as the decade neared its end.

A significant reason for Germany’s lack of noteworthy cinematic achievements was the undeniable fact that so much creative talent had fled the country in the early 1930s after the rise of Adolf Hitler and the Third Reich. Unlike their Axis partners Italy and Japan, the German film industry had to endure a mass exodus of devastating proportions. Even when the studios were rebuilt and funding was made available, there didn’t seem to be a group of artists who were ready to take the risks necessary to tell original, compelling stories that would transcend the need for mundane, locally based entertainment and capture the attention of a non-German audience. And that had a lot to do with Germany’s extremely problematic recent history. This proud society, divided against itself into East and West, directly centered in the cross hairs of the Cold War, had a hard time grappling with its defeat, and probably even worse, its heinous responsibility for dragging Europe and the rest of the world into history’s most cataclysmic war. It’s difficult to make great art under such circumstances, especially when international audiences still felt like they were owed some kind of apology.

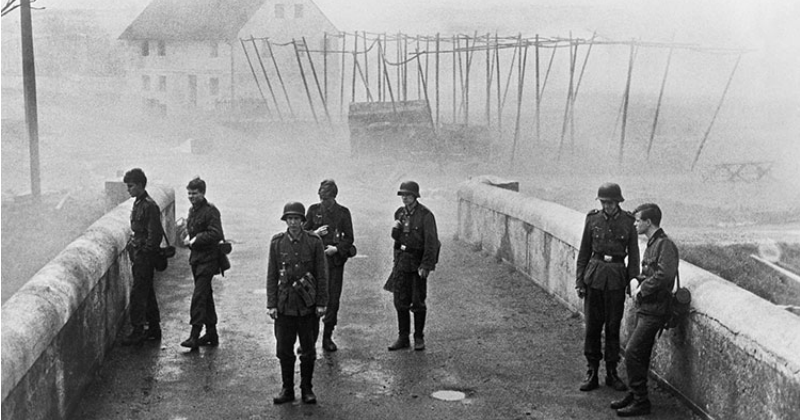

Even though The Bridge doesn’t exactly amount to a formal statement of contrition on the part of the German people, this powerful and gripping story set in the final days of World War II certainly went a long way toward reintegrating that nation’s cinema and culture into the good graces of their Western neighbors. Released in theaters in 1959, and on Blu-ray and DVD today by the Criterion Collection, it tells the story, based on circumstances personally experience by the author of the source material, of a group of seven teenage boys conscripted into the German army and pressed into battle before they’d even completed one full day of basic training. In late April 1945, the country was being overrun by swarms of American and Soviet troops that operated almost with impunity on their relentless march to Berlin. The Allied forces were conducting an accelerated land grab, and it was at this crucial hour that many of the small towns that had escaped wartime ravages due to their lack of strategic importance finally got a taste of the chaos and destruction that engulfed the rest of the Continent over the past several years. And in this one particular village, a modest bridge that crossed an inconsequential river was transformed over the space of a few hours into a battleground that underscored the futility and madness that drives wars of all sizes and durations.

But before the climactic battle gets underway, director Bernhard Wicki takes his deliberate time allowing us to get to know each of the boys in this ill-fated troop as individuals. Young men just coming into that stage of life where their thirst for adventure and eagerness to plunge into the privileges of manhood outpaces their actual ability to perform such tasks, despite their brash confidence and sense of readiness for the challenge. When we first meet them, they’re restless classmates, bored as the school year nears its end and profoundly distracted by the excitement of rapidly approaching battle lines. As multi-year veterans of the Hitler Youth program, they’ve been indoctrinated with all the slogans, rallying cries and propaganda necessary to convince them of their obligations to defend the Fatherland, should duty call. And we also get to see illustrative snippets of their domestic lives, as they each chafe in their own way against ordinary family and relationship pressures that are common across all societies at that age. But as is almost always the case when crisis sets in, the dogmatic cliches and stern discipline that were impressed upon them by the authority figures in their lives turn out on the one hand to be unreliable when directly undercut by the confusion and hypocrisy of those responsible for calling the shots, and on the other hand, terribly self-destructive when those same flawed principles and beliefs are adhered to so rigidly that they overwhelm basic survival instincts and common sense when confronting a superior aggressor in the field of battle. But I don’t want to give too much away in this regard – the less known about the cathartic final half of the film, the better, since the stakes are high and the outcome is unpredictable. The emotional impact that The Bridge is capable of delivering deserves that initial “clean” viewing if at all possible. However, here is Criterion’s “Three Reasons” video for the film, which basically shows just snippets of what I’ve already alluded to above.

Enhancing our appreciation of this bold and ground-breaking film (what other titles can be named from this era that dare to stir up audience sympathies for soldiers fighting on Hitler’s behalf?) is a fine array of supplements that effectively put The Bridge in its historic and cultural context. Though such special features are at this point practically routine and to be expected, the selection here rounds out the picture from numerous helpful angles. Among them is a 1989 interview with Bernhard Wicki, a concentration camp survivor and popular actor of the mid-1950s who hardly seemed like he would be the man to revive German cinema from its doldrums. This was his first directorial effort, released when he was 40 years old, and he made it with a clear determination that he was going to transform a popular story that emphasized on the heroic bravery of the boy soldiers into a powerful antiwar statement that would speak clearly to his domestic audience. Wicki was very proud of his film’s lasting reputation as a classic expression of humanitarian values, and a prize is awarded in his name each year for distinguished filmmaking that advances the cause of peace. Though Wicki never went on to become a big international star, he does have important roles in a couple other Criterion films that many readers here have seen: Michelangelo Antonioni’s La Notte and Wim Wenders’ Paris Texas. We’re also given the opportunity to hear from his widow, Elisabeth Wicki-Endriss, who shares her perspective on how the film was made in an excerpt from a documentary she directed to honor her husband’s legacy.

Another interview with German director Volker Schlondorff, recorded earlier this year, pays tribute to a man who he deeply admired and respected in his youth, well before he ever started making films himself. Schlondorff speaks at length about his disenchantment with the state of German cinema when he was coming of age, and how Wicki’s ingenious twist on what appeared at first glance to be just another self-congratulatory war movie of the sort common at that time provided a critical opening for him and other young directors in the 1960s as the “New German Cinema” established itself.

And the most riveting segment of all these special features, in my opinion, is an interview recorded just a few months ago with the author Gregor Dorfmeister, whose novel, also titled The Bridge, was adapted for the screen. By now he’s a very old man, and his apparent frailty suggests that they got him to tell his stories on video just in the nick of time. His personal recollections of events that have their rough cinematic parallel in the film are quite compelling, and they truly magnify the depth and intensity of what we see on the screen, even when he explains aspects of the story that vary significantly from the movie.

As an entry in the Criterion Collection, The Bridge definitely serves that function implied in the title, if you’ll forgive the play on words, in bringing together two important but chronologically distant eras in German cinema. It’s the only movie from that nation to have earned a Criterion release between Fritz Lang’s The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933) and Volker Schlondorff’s Young Törless (1966). Historic considerations aside, it’s also a dynamic and engaging film, beautifully rendered in a crisp 2K restoration, with remarkable performances from a largely novice/amateur cast (the boys in particular) and most importantly, a clear and resonant message that the world still needs to comprehend and act upon.

Buy The Film On Amazon: