Over the course of the past century, there’s been no shortage of films in which the directors drew heavily on their personal autobiography to supply their subject matter. Among that vast archive, the subset of movies that proceed to choreograph their creators’ eventual death is quite a bit smaller. One example from that category that I recently viewed is Yukio Mishima’s Patriotism, in which the celebrated Japanese author adapted a short story describing in lurid and precise detail the process of seppuku and the exquisite enticements of intensive pain and masochistic pleasure that eventually led Mishima to reenact that ritual in real life a few years after he directed his one and only film. Another offering in this vein was recently added to the Criterion Collection: Bob Fosse’s All That Jazz, in which the highly influential choreographer staged what amounts to an idealized and impeccably staged version of his own exit from this world, complete with celebrity cameos, disco-era stage lighting, a cast of hundreds and a warped, darkly hilarious musical soundtrack to send him on his way into eternity. Beyond those surface similarities, the contrasts between Patriotism‘s unrelenting seriousness and the flippant irreverence that permeates All That Jazz could not be more pronounced, other than to point out that in both films, every important move that we see on screen is planned with thoroughly thought-out precision.

But before we get to that grim (and strangely life-affirming) finale, let’s take a few minutes to appreciate so much of the celebratory goodness and vitality that went into the creation of All That Jazz, a film that more or less serves as Bob Fosse’s most readily accessible record of his life’s work and legacy. For those who don’t recognize the name, Fosse was one of the most influential and innovative dance masters of his era. His sensual and provocative approach had a revolutionary effect, adapting the traditions that had been established in the first half of the 20th century in Hollywood and Broadway based musical production numbers to the more explicit sensibilities that gained traction in the 1960s and ’70s. In particular, his output in 1972, in which he pulled off the unprecedented and still unequaled feat of winning an Oscar, an Emmy and a Tony Award all in the same year, basically cemented his lasting reputation as a major theatrical force to be reckoned with. As is so often the case with artistic trailblazers, his impact on subsequent creative talents never quite generated comparable box office returns that more crowd-pleasing imitators and marketers are able to generate, but that relative obscurity only serves to make Fosse a more attractive commodity for a company like Criterion to embrace. Fosse’s risky forays into material that deeply challenged (but also gratified) his audience was never given a more pronounced framing than we we get in this film, released just before Christmas 1979, as it ushered out one of my favorite decades in all of American popular culture, bringing the curtain down on the Seventies in one glorious celebration of sex, death and the vitality of life itself that links those two primal powers governing our existence.

All That Jazz tells the story of Joe Gideon, a chain-smoking, hard-driving, pill-popping alcoholic womanizer who also happens to be a supremely talented designer of dance routines. Gideon is much in demand by showbiz movers and shakers, though he’s almost equally feared and distrusted by those same influencers due to the disruptive twists he frequently tosses into his creative efforts. We’re introduced to Gideon in a powerful opening scene as he magistrates over an open casting call, sifting through a crowd of hundreds of hopeful recruits all looking to get a potentially star-making (or at least rent-paying) gig in his latest production. The scene is scored to George Benson’s hit recording of “On Broadway,” and effectively serves notice that this is a film intent on grabbing the attention of its audience and not letting go until its creator is good and ready to turn us loose after getting its message across.

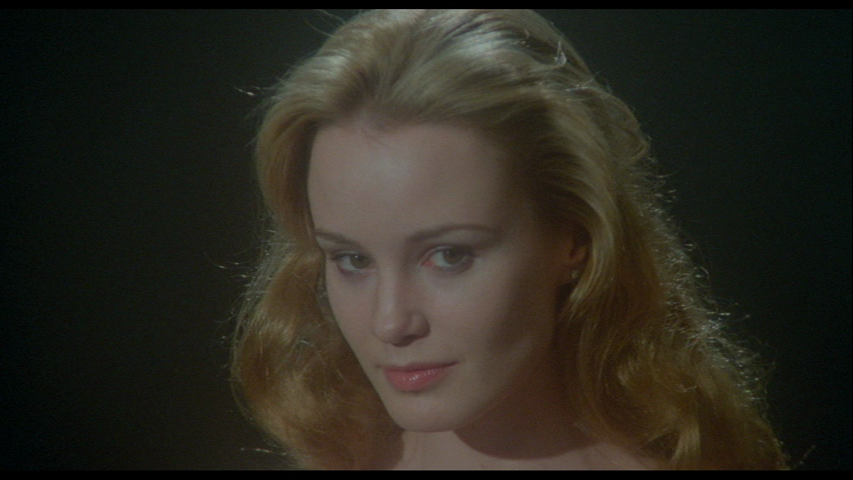

Once we’re launched into the dancer’s world and all its attendant backstage intrigues, we swiftly find ourselves in the self-generated whirlwind of Gideon’s life. He’s beset on all sides by pressures from past and present lovers, a neglected preteen daughter who craves his attention, producers demanding accountability for the dollars they’ve entrusted to him and various sycophants seeking to hitch their fortune to his obvious success. Little do any but those most intimately connected to Joe suspect just how fragile the focus of their attention actually turns out to be. Gideon is on the fast track to oblivion, as a few decades of hard living fueled by nicotine, booze and amphetamines takes its inevitable toll on his body and psyche. Still, it’s not enough to slow down or temper Joe’s ambitions – he just ups the dosage and blasts on through, led by his impulses and instincts to do whatever it will take to chart the next routine, seduce the nubile dancer eager to gain a casting advantage or brush off the flunky dispatched by his producer to bring the show back under budget and on time. Between his almost continuous blur of activities and obligations, Gideon finds his alone time increasingly disrupted by the increasingly hard-to-ignore presence of Angelique, a beautiful otherworldly messenger played by Jessica Lange in her second screen role (after her memorable debut in the 1976 remake of King Kong). She’s a guardian of a post-mortal realm that Joe has been pondering for most of his life and now senses is drawing nearer than ever. Functioning as part Grim Reaper, part Fairy Godmother, Angelique is basically on the scene to help Joe make his final reckoning, if not quite reconciliation, with all the busted up relationships that trail behind him after his 50-odd years of life so far.

Fosse’s method of telling the story is that of a rapidly-cut phantasmagoria, alternating between unvarnished rehearsal sequences that show the creative process stripped of its glamour and focused on the grit, scenes of domestic clashes where Gideon is forced to come to terms with the heartaches and disappointments caused by his infidelities and vain ambitions, and the swirl of memories and fantasies that have fueled his drive to project himself as something other than the wretched fake and failure that he views himself as when left alone with his thoughts. It’s a supremely potent, enthralling mix, loaded with an abundance of psychological symbolism that reveals new layers of creative intelligence through multiple viewings, once our astonishment at the sheer energetic power of the performances has settled into a degree of relative comfort and familiarity.

Running just a bit over two hours, All That Jazz divides up neatly into four distinctive half-hour segments. The first quarter of the film simply establishes the pace and setting of the film, acclimating us to some of the mysteries yet to be revealed without stopping too long to explain the more puzzling moments he casually tosses in. Once we’ve discovered what a scoundrel Gideon is, and the kinds of pressures he’s operating under, the second quarter reveals his creative rebellion as he reinterprets a banal standard Broadway production number into an astonishing eruption of “Air-otica” that, among other distinguishing attributes, “loses the family audience” and is simply too hot to post on this site. Suffice it to say that the scene definitely rewards the upgrade to Blu-ray for anyone who purchased any of the DVD versions released over the past dozen years or so.

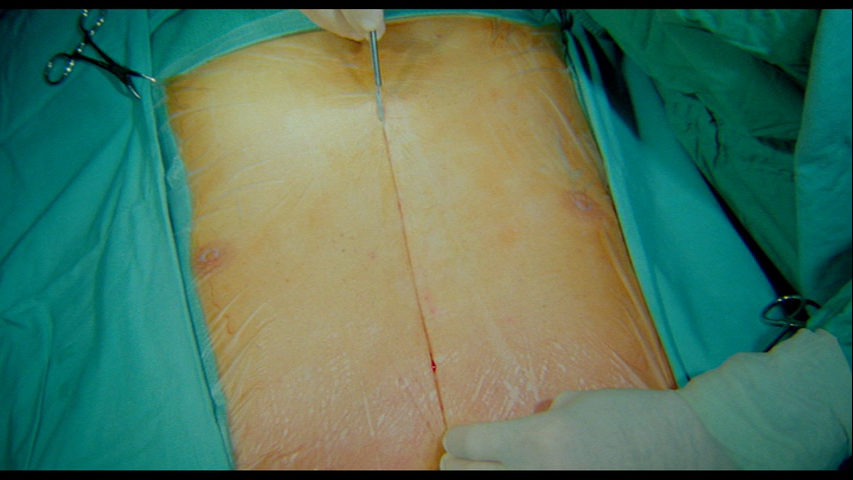

The second hour of the film shifts the focus from Joe’s work life, which is becoming increasingly banal and unfulfilling despite the creative challenges it poses, to his domestic sphere, where the needs of his current lover Kate and daughter Michelle belatedly start receiving more of his attention. They capture his gaze (and ours) by virtue of an adorable dance routine they perform on the stairs and floor of the home they share. It’s a welcome humanizing moment for Gideon and his clan, but the tranquility is short-lived. As the pressure of bad reviews of his latest film production (about a stand-up comedian modeled after Lenny Bruce) break through the insulation of happy talk that his agent tries to maintain around him, Joe’s heart begins to give out on him, leading to one of the most brutally jarring intrusions ever seen (before or since) in the musical comedy genre. We’re ushered into a different kind of theater, that of the surgical variety, in order to get a brief but raw glimpse at open heart surgery. I well remember how shocking and unprecedented that scene was when I saw the film in the winter of 1980. Cinema has made such images a lot more commonplace and quite a bit less unsettling since then, but it’s still powerful stuff, seeing an actual human chest split open simply for the sake of our entertainment… and maybe a note of forewarning.

The final half-hour of All That Jazz fully lives up to just about any praise bestowed on the film, in my opinion. It’s a full-fledged eruption of Fosse/Gideon’s psyche, the portrayal of all the guilt, fear, cynicism, aspiration, creative genius and desperate clutching after life’s elusive pleasures that has accrued in his twisted and fragmented soul over the course of a lifetime. Played out as a tacky yet superbly realized showstopping production number starring that quintessential showman of the late 1970s Ben Vereen, Gideon himself takes center stage, putting Roy Scheider’s acting (read: dancing) talents to their supreme test as he channels the angst and inner tumult that Fosse wrote into the character of his alter-ego. A bit of cinematic and editing sleight of hand helped Scheider get through the scenes with his credibility intact, but even if he had tripped and stumbled a bit, there’s so much going on in this last stretch that I doubt many viewers would have noticed. Between the ingenious subversion of the Everly Brothers’ “Bye Bye Love,” the garish costumes and set designs and the audacious, absurd theatricalization of a dying man’s final moments on Earth, this extended scene holds up extraordinarily well over repeat viewings, provided one has a taste for fatalistic humor of a bitterly bleak vintage.

This is a film I saw several times as a young adult in its original theatrical run, leaving a big impression on me over the years, and I was quite excited to see it announced as a late summer Criterion release. (Sadly, it’s also destined to be the last title they put forth in a dual-format Blu-ray/DVD package… at least for now. I hope they change their mind some day.) Though most of the details from those initial viewings had faded from my memory over the subsequent years, the powerful impressions remained and I wasn’t disappointed in the slightest by the return visit. The rich surround-sound audio track and sharp 4K image transfer provide an overwhelming sensory experience, and the voluminous supplements (featuring interviews with the director, members of his cast, his production assistants and peers, along with a host of other musicians and dancers who consider themselves indebted to Fosse,) add substantial layers of depth that open up new angles of appreciation on what I consider to be a truly great movie and a landmark in my own lifelong exploration of what cinema can accomplish and reveal.